![]()

1 Introduction

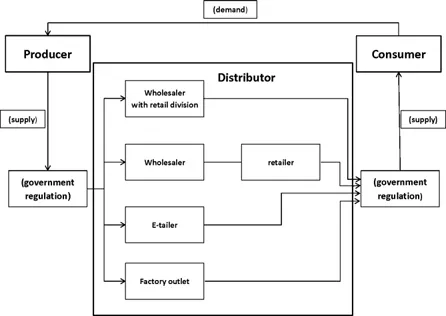

The retail sector is an integral part of a nation’s economy. From the political economy point of view, all consumer goods have surplus values locked up in them; the surplus values are not realized until the consumer goods are purchased by consumers through various distribution channels (Blomley, 1996). As such, retailing is the essential link between production and consumption, and the accumulation of capital is achieved through “repeated acts of exchange” between consumers and retailers (Ducatel & Blomley, 1990, p. 218). The dynamics of a nation’s economy therefore cannot be fully understood without a good understanding of its retail sector (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The role of retailing in the system of commodity circulation.

(Retailing is carried out by a variety of distributors. They link forward with consumers, and backward with producers/suppliers. Governments regulate the circulation system and the relationships both between distributors and producers and between distributors and consumers.)

Retailing is especially important in the urban economy. Cities are not only centers of power and prestige; they are also centers of consumption and concentrations of retail businesses. Distribution of goods between retailers and consumers is among the chief economic activities of urban areas (Hartshorn, 1992). Knox (1991) even had the view that “the whole of the [urban] landscape is geared toward consumption.” Whereas retail activities occupy only a small proportion of the developed urban land, they play several important roles including the generation of large amounts of retail employment while serving as the centers of consumption (Yeates, 1998). As production firms become more mobile, the success of cities hinges more and more on the role of cities as centers of consumption (Glaeser et al., 2000).

In the last three decades, a series of revolutionary changes have taken place in the retail industry worldwide amid the process of globalization of the world economy. Most of these changes originated in the Western capitalist economies, but they quickly spread to the emerging markets in Asia, Latin America, and, to a lesser extent, Africa. Among the emerging markets, China has been the new frontier for much of international business, and the transformation of its retail economy should be the most profound, including the disengagement of the state in operating retail stores, the entry of international retailers, and the emergence of non-state enterprises.

Despite its importance, there has been a lack of attention to the restructuring and transformation of China’s retail sector in the large body of literature concerning economic reform and regional development in China. For one example, among Routledge’s publications of its Contemporary China Series and its series of Studies on China in Transition (over 60 titles in total), no book deals with China’s burgeoning retail economy. The four existing books printed by other publishers all focus on one aspect of China’s retail economy—retail internationalization—and their studies are “firm centric” (see Zhen, 2007; Chevalier & Lu, 2010; Gamble, 2011; Siebers, 2011). This book is written to fill the gap. It goes beyond retail internationalization and moves away from the “firm-centric” approach. The book aims to achieve three broad objectives. First, it provides a comprehensive assessment of the changing consumption patterns, the current size of the Chinese consumer market, and the regional variations within the vast country. This assessment of “demand” establishes the fundamental context for a subsequent examination of the changes in the “supply” side. Second, the book delivers a systematic interpretation of the transformation of China’s retail economy in the last three decades. This includes the entry and expansion of foreign retailers, the development of indigenous retail chains as a national strategy to modernize China’s retail industry, the changing retailer-supplier relations, and the resultant structural changes in the retail sector. Third, it examines the changes in the regulatory system and the corresponding policy initiatives. While all major retail corporations (both domestic and foreign) have their own geo-strategies, their geo-strategies are largely dictated by the state spatial strategies of the Chinese government.

The book is written with the approach of the new geography of retailing advocated by Lowe and Wrigley (1996) and using the economic transition process for post-socialist states, as generalized by Bradshaw (1996), as a theoretical framework, for a deep understanding of the transformation of China’s retail economy. The changes in China are also analyzed and interpreted in contrast to the characteristics and recent trends of the contemporary capitalist retail economy.

CHARACTERISTICS OF THE CONTEMPORARY CAPITALIST RETAIL ECONOMY AND RECENT TRENDS

From the vast literature on retail structure and structural changes in the Western capitalist economies, it is possible to generalize the following major characteristics and trends.

1. Private ownership predominates in the retailer sector, but government intervenes through regulatory measures.

Within the capitalist market economy, retailing is defined as private sector activities that provide goods directly to consumers (Simmons & Kamiki-hara, 2003). Governments rarely own or operate retail businesses, except for a few selected consumer goods (i.e., non-merit goods such as alcoholic beverages and cigarettes). For example, in the Province of Ontario in Canada, all liquor stores are owned and operated by the Liquor Control Board of Ontario—a provincial government enterprise. Whereas corporations and individual entrepreneurs enjoy a high degree of freedom in business decision making, governments do intervene in the retail industry with regulatory measures, often in the form of public policies, to mitigate negative impacts (see Figure 1.1). In turn, these policies, which are supposed to reflect the values of society, impose limits on the retailer’s freedom to deal with competitors and conduct business with suppliers and consumers, thus affecting retail operations and the overall market structure.

Dawson (1980) has generalized five types of public intervention that commonly exist in the Western capitalist economies: (1) location restriction through land use planning and zoning bylaws to minimize spatial externalities; (2) price control to protect consumers from inadequate advertising and predatory selling practices, and to generate revenues for governments; (3) optimization of business structure through fair competition laws to prevent monopoly and encourage innovation; (4) promotion of business efficiency by controlling new entries into a market to avoid excess retail capacities and waste of economic resources; and (5) protection of consumer well-being and safety through licensing/inspections and compulsory labeling. Dawson (1980) also pointed out that whereas direct policies toward retailing are few, indirect policies that aim at other sectors but impinge on retailing are abundant. The various types of public intervention are often imposed by different levels of government and implemented at different spatial scales (Jones & Simmons, 1993).

2. A planned hierarchy of shopping centers is common in metropolitan cities.

This is perhaps the most conspicuous in North American cities, where “there are more shopping centers than movie theatres; and there are more enclosed malls than cities” (Kowinski, 1985, p. 20). The rapid progress of suburbanization in the late 1950s and the 1960s required that cities be planned following “the principle of hierarchical organization” (Wang & Smith, 1997). Accordingly, a hierarchy of shopping centers was incorporated in this form of planning, consisting of neighborhood, community, and regional shopping centers. Each type of shopping center had a clearly prescribed tenant mix, trade area size, and even physical form (Urban Land Institute, 1985). In the 1970s, a newer and larger type of shopping center—the super-regional shopping center—began to be built. These centers often combine entertainment and recreation with shopping under one roof, becoming a new palace of consumption. Typical examples are the West Edmonton Mall in Canada (493,000m2) and the Mall of America in the United States (466,000m2). As suburbanization continued, the metropolitan city became multicentric, and a network of retail nodes evolved to serve the expansive city. Each regional and super-regional shopping center became a node, spatially distributed in a hierarchical fashion analogous to central places in Christaller’s Central Place Model (Yeates, 1998).

3. Big box stores and power centers have emerged to become new leading retailers.

By the late 1980s, retailing re-emerged as an important and dynamic economic sector in many developed nations. In addition, major technological innovations took place in the distribution system. The highly computerized goods-tracking systems and inventory control enabled direct communications with, and direct shipping from, manufacturers (Hughes & Seneca, 1997). In the process, it spawned urban shopping environments and led to the emergence of a new retail format, known as ‘big box’ stores. At first, such stores were freestanding outside shopping centers; but eventually several big box stores began to cluster together at one location in the form of a planned plaza, commonly called a ‘power center’ (also known as a retail park). In less than ten years, this new format has been adopted by a variety of retail businesses. The big box stores and power centers have become leading retailers in the Western retail system (Jones & Doucet, 1999; Hernandez & Simmons, 2006) and have been widely blamed as the cause of the ‘graying’ of regional and super-regional shopping centers and the demise of department stores in North American cities (Kmitta & Ball, 2001; Doucet, 2001). These new retail spaces have been created and manipulated by the innovative retailers and commercial real estate developers to induce consumption.

4. Retail chains continue to be the most important form of retail concentration, but significant restructuring and reshuffling have been taking place in the retail industry.

With no exception, all retail giants are chain operators, as the retail chain provides a way of introducing scale economies while avoiding the restrictions of market size (Jones & Simmons, 1993). Retail chains often account for 70 percent or more of the total retail sales in a metropolitan market. The 1990s and the 2000s witnessed significant restructuring of retail chains, leading to concentration of retail capital into the hands of a few “super leagues” (Marsden & Wrigley, 1996). Some sought to acquire, or merge with, others to consolidate resources and rose to the status of global corporations. For example, in 1991, the French firm Carrefour took over two other domestic hypermarket chains: Euromarche and Montlaur. In 1999, it merged with Promodes to create the largest European food retailing group and the second largest worldwide.

In 2002, the American electronics retailer, Best Buy, expanded by acquiring Future Shop, a Canadian retail chain. Big capital retailers are better able to invest heavily in information technology and centralized distribution systems, the use of which enables the retailers to more effectively perform their competitive functions of reducing the turnover time of commodities (Hughes, 1996). Meanwhile, many other chains were not as fortunate and subsequently went under. Eaton’s, a Canadian department store chain with a history of more than 100 years, was one such victim.

5. The retailer-supplier relationship has tipped toward retailers.

For many years, producers of consumer goods effectively dictated brands and types of products being sold as well as their price in the retail market. Since the 1980s, retailing has been shifting from being the sales agent for manufacturing and agriculture to being the production agent for consumers, and the balance of the retailer-supplier relationship has tipped toward the large retail chains (Dawson, 2008). The significant retailers are no longer passive receivers of consumer goods supplied to them by producers. While still mediating between consumers and producers, they are no longer neutral mediators. Instead, they influence consumers by selecting goods with larger profit margins (Foord et al., 1996). They erode manufacturers’ share of the surplus value by influencing patterns of consumption in their own favor and by using their bargaining power to lock manufacturers into retailer-led supply situations (Hughes, 1996, p. 99). They also aggressively develop “own-label” products as a competitive strategy. With their significant purchasing and bargaining power, they manage to exploit “negative working-capital cycles” by negotiating for extended credit payment periods, to reduce circulation costs and to accelerate accumulation of capital (Marsden & Wrigley, 1996). Pressure is often placed on suppliers to develop just-in-time production programs and factory-to-warehouse distribution systems to match the demands of the retailers.

6. Internationalization of retailing has intensified.

As their home markets became saturated, large retail chains were motivated to explore foreign markets, using a variety of paths ranging from licensing and franchising to joint ventures and wholly-owned subsidiaries. Almost every successful large retail chain has been seeking possibilities for expansion into other countries (Simmons & Kamikihara, 1999). Initially, they chose markets that had the least physical and cultural distances in order to minimize cost and the degree of uncertainty about sourcing and operation. In recent years, the major international retailers have increasingly turned their attentions to the ‘emerging markets’ in Asia and Latin America (Nakata & Sivakumar, 1997; Wrigley, 2000). Wal-Mart became an international company in 1991. By 2012, it has more than 5,000 stores in 26 countries, including 370 in China (Wal-Mart China, 2012). Carre-four, which went international in the 1970s, has also intensified its overseas operations since the late 1980s. It now operates 9,500 stores in 32 countries, including 361 in China (Carrefour Corporate Website, 2012). Revenue from their overseas operations has become an increasingly important part of business success, or even survival, for many multinational retailers.

7. E-tailing has been gaining increased popularity.

In the early 1990s, a new agent of retailing and a new form of retail space— online shopping and web stores—came into being. This led to the creation of the famous Amazon in 1995 and eBay in 1996. Online shopping is one form of electronic commerce, whereby consumers purchase goods (or services) from a seller over the Internet, without having to visit a brick-and-mortar store. Shoppers must have access to a computer connected to the Internet and a method of electronic payment—typically a credit card. Once a payment is received (usually through a third-party e-commerce business that facilitates online money transfer between consumers and retailers, such as Paypal), the goods can be shipped to a prescribed address via post or courier services, or they can be picked up by the consumer from a nearby store.

Most people tend to think that web stores are virtual space, but the e-(re) tailers do need to set up such physical facilities as warehouses and regional distribution centers by either constructing new buildings or leasing existing spaces, thus requiring heavy monetary investment. These facilities are necessary in order for online retailers to reduce delivery time and cost.

Initially, online shoppers were deterred by fraud and privacy concerns, such as risks of cyber theft to steal credit card numbers and identity. In recent years, such risks have been greatly reduced by the use of Secure Sockets Layer (SSL) encryption and firewalls, and e-tailers improved their refund policies. As a result, more and more consumers are encouraged to shop online for the benefits of convenience and saving, as the web stores are open all year round with no after-business hours and with no restrictions by location and distance.

The increased popularity of online shopping is leading to another revolution in the retail industry. In the new world order of retail, shoppers have become more tech savvy, even using smartphones to shop, order, and pay; or they go to a store to look at and feel a product, and then buy it online from Amazon, turning the brick-and-mortar stores into show rooms. Not all merchandise have the same level of suitability for sale online. Yet, e-tailers have been expanding their offerings, taking market shares away from the brick-and-mortar retailers. Amazon continues to be on the march, successfully moving into merchandise that Wal-Mart traditionally has sold. In the 2011 fiscal year, Amazon posted an impressive 41 percent revenue growth, compared with 8 percent at Wal-Mart, putting pressure on Wal-Mart to fix its lagging e-commerce operation (Welch, 2012). In response, Wal-Mart is investing heavily to revamp and expand its online shopping system with a new motto, “Anytime, Anywhere.” To reduce overall cost to consumers, Wal-Mart aims to use its stores as pickup centers, instead of shipping the products from a distribution center. More retailers responded to the new shopping pattern by offering both multi-channel retailing (sell both in store and online in parallel) and cross-channel retailing (order online but pick up in store).

THE NEW GEOGRAPHY OF RETAILING: A PARADIGM SHIFT

Retailing is a subject of study by two schools of scholars and students— business management and geography—but they approach the subject from different perspectives. The former concentrates on firms and business organizations, including logistics, merchandising, marketing, consumer behavior, in-...