![]()

The Nagoya-Kuala Lumpur Supplementary Protocol on Liability and Redress

Akiho Shibata

The adoption of the Nagoya-Kuala Lumpur Supplementary Protocol on Liability and Redress to the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety (Supplementary Protocol) on 15 October 2010 in Nagoya, Japan,1 was an epoch-making event both for the field of environmental diplomacy and for academia interested in the study of international environmental law generally, and environmental liability in particular. The Supplementary Protocol provides international rules and procedures in the field of liability and redress relating to living modified organisms (LMOs) in response to damage caused by those LMOs to the conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity, taking also into account risks to human health.

The adoption of the Supplementary Protocol came when the international community was still suffering from the Copenhagen disaster in December 2009, where climate change negotiations collapsed, and was losing confidence in multilateral environmental diplomacy. Indeed, the Supplementary Protocol was the first universal environmental treaty adopted since the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants in 2001. The political configuration of environmental treaty negotiations had undergone a significant change in the first decade of the twenty-first century, and the international community was searching for new ways to effectively create international environmental law.2 Similar to the climate change negotiations, the issue of LMOs in general and the legal design for liability arising from them in particular could no longer be seen as a simple north-south divide, as had previously been the case in 2000 when the Cartagena Protocol on Biosafety (Cartagena Protocol),3 with its controversial Article 27 on liability and redress, was adopted.4

How was the adoption by consensus of the Supplementary Protocol at Nagoya possible both substantively and procedurally? By inviting the Co-Chairs of the negotiating group and the negotiators and advisors from the key negotiating Parties, including the African Union, the European Union, Japan, Malaysia, Mexico, Namibia and South Africa to contribute, this book delves into the minds of those who were at the forefront of the extremely intricate negotiations.

On a more profound, theoretical level, the Supplementary Protocol was negotiated and adopted when, within the academia, the ‘sensibility’ of negotiating an international environmental liability regime was seriously questioned.5 The Protocol on Liability and Compensation for Damage resulting from Transboundary Movement of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal under the Basel Convention (Basel Liability Protocol), adopted in 1999, has not attracted many ratifications from the Parties to the Basel Convention and still has not entered into force.6 The same is true for liability regimes negotiated and adopted within the European context in previous decades.7 The United Nations’ International Law Commission (ILC) has been wandering over the concept of ‘international liability’ since 1978,8 and in 2006, adopted instead the ‘Principles on Allocation of Loss in the Case of Transboundary Harm Arising out of Hazardous Activities’.9 The initial enthusiasm for developing international civil liability regimes, forcibly urged in Principle 13 of the 1992 Rio Declaration on Environment and Development,10 seemed to fade. As an attempt to find a way out of this liability occlusion, the Supplementary Protocol, while retaining the concept of liability and redress, has taken an innovative approach that is now widely called the ‘administrative approach’ to liability. The legal structure of this new liability regime that commanded consensus of the negotiating Parties at Nagoya needs detailed and critical examination; this is the primary aim of this book.

The Supplementary Protocol deals with damage caused by LMOs, a politically and socially sensitive issue.11 An LMO is defined in the Cartagena Protocol as ‘any living organism that possesses a novel combination of genetic material obtained through the use of modern biotechnology’. The term ‘modern biotechnology’ in turn is defined as the application of (a) in vitro nucleic acid techniques, including recombinant deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and direct injection of nucleic acid into cells or organelles; or (b) fusion of cells beyond the taxonomic family, which overcome natural physiological reproductive or recombination barriers and are not techniques used in traditional breeding and selection.12

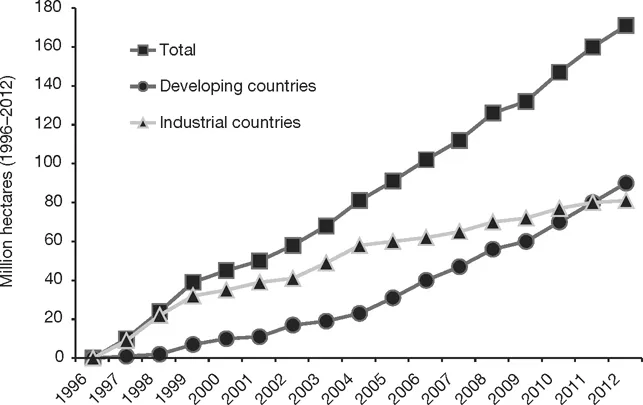

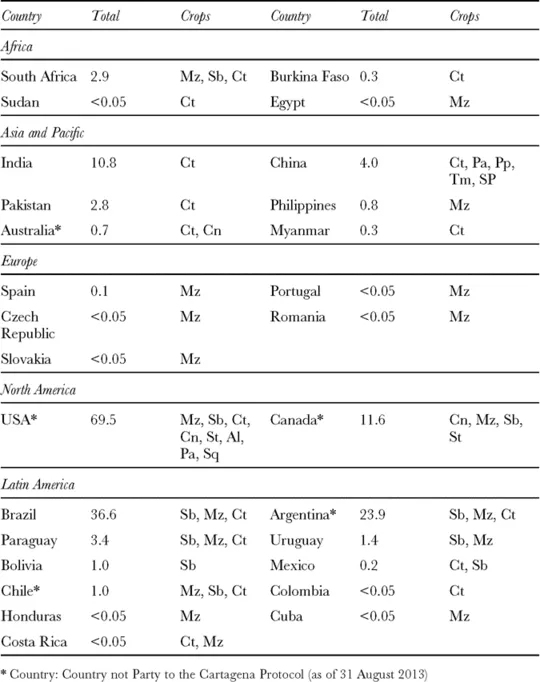

The international community acknowledges both the benefits13 and the risks14 of biotechnology, which is still developing and progressing. By addressing LMOs, the new treaty intends to regulate certain consequences arising from the utilisation of biotechnology for both research and commercial purposes, particularly in the agricultural sector. Thus, the Supplementary Protocol is at the forefront of science and technology and their applications.15 At the same time, genetically modified (GM) crops such as GM soybeans and GM canola have already been produced in large quantities and marketed globally. The area and the number of countries producing such GM crops and vegetables/fruits are steadily increasing across all five continents (see Figure 1.1 and Table 1.1). If one includes LMOs used in laboratory research, field trials for public health purposes16 and industrial applications,17 the use of LMOs can now be considered as ubiquitous in modern society.

Figure 1.1 Global area of biotech crops in million hectares (1996–2012)

Source: International Service for Acquisition of Agri-Biotech Applications (IASSS), Brief 44: Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops: 2012. www.isaaa.org/resources/publications/briefs/44/ (accessed 1 August 2013).

Table 1.1 Global area of biotech crops by country 2012 (million hectares)

Al: Alfalfa; Cn: Canola; Ct: Cotton; Mz: Maize; Pa: Papaya; Pp: Poplur; Sb: Soybean; SP: Sweet Potato; Sq: Squash; St: Sugar Beet; Tm: Tomato

Source: International Service for Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications (IASSS), Brief 44: Global Status of Commercialized Biotech/GM Crops: 2012. www.isaaa.org/resources/publications/briefs/44/ (accessed 1 August 2013).

However, unlike oil spills polluting the ocean or nuclear power plant accidents spreading radioactive material, there has not yet been a scientifically confirmed case of environmental damage caused by LMOs. The treaty negotiators were tackling a hypothetical problem of environmental damage that may potentially be caused by LMOs without any actual experience of it. The state-of-the-art science and technology involved in LMOs, their already complex global supply chains and the lack of actual environmental damage caused by them to date have been identified as formidable challenges in designing a liability regime involving LMOs, for which existing liability regimes may not serve as a complete model.18

During the negotiation of the Supplementary Protocol, some participants (some with good and some with bad intentions) tried to revive the political, social and even emotional divide over LMOs that had been partially sealed off by the Cartagena Protocol. A lack of actual cases of environmental damage caused by LMOs allowed, on the one hand, idealistic and sometimes emotional claims of establishing an impenetrable liability regime responding to all hypothetically conceivable scenarios including catastrophic events. On the other hand, it also prompted conservative and sometimes hostile attitudes towards the practical necessity of such a regime. However, the adept Co-Chairs of the negotiating group steered the discussion towards a focus on the technicalities of the legal structure of an acceptable liability regime, taking full account of the realities of the ‘GM world’ as described above.

Unlike the negotiations over a climate change regime or the Nagoya Protocol on access and benefit-sharing (ABS) relating to genetic resources,19 the substantive negotiation of the Supplementary Protocol rarely involved ministers or other political figures. It was conducted mostly by those officers responsible for administrative management of LMOs and their legal advisors who knew the substantive issues the best. Pragmatism prevailed in the negotiation. The non-politicisation of the negotiation achieved by focusing on the practical and legal issues of a liability regime for biodiversity damage was one important factor in the successful adoption of the Supplementary Protocol. The Supplementary Protocol keeps a fair distance from potentially divisive issues related to LMOs themselves, essentially by freezing the controversy and leaving them to the determination of each State. The result was the insertion in 18 places in the Supplementary Protocol of the famous phrase: ‘in accordance with its domestic law’.

Thus, the Supplementary Protocol was able to shelve many of the potential difficulties and complexities particular to biotechnology and LMOs.20 Instead, its legal design is premised mainly on addressing biodiversity damage in an international liability regime. This aspect of the Supplementary Protocol may have profound precedential and theoretical implications that reach beyond LMOs and biotechnology.

The Supplementary Protocol addresses damage that is defined as ‘an adverse effect on conservation and sustainable use of biological diversity, taking also into account risks to human health’ (Article 2 (2) (b) and Article 2 (3)).21 This is the first ever global treaty that defines ‘biodiversity damage’ and establishes the legal consequences arising from such damage. As international law continues to grapple with a generally acceptable concept of environmental damage,22 the agreement on the concept of biodiversity damage and, more significantly, on its legal consequences was almost a miracle, especially in the context of the treaty negotiated under the United Nations auspices by 160 or so Parties to the Cartagena Protocol. This miracle, however, had been achieved by extensive political compromise and adept drafting technique, making the Supplementary Protocol difficult to comprehend for first-time readers. This book will shed light on some of the most controversial, and thus most difficult-to-read, provisions of the Supplemental Protocol.

This book does not intend to be a comprehensive commentary on all 21 articles and five preambular paragraphs of the Supplementary Protocol. Instead, this book examines in depth the highlights of the Supplementary Protocol from the per - spective of both the negotiators and academia. The most significant feature of the Supplementary Protocol from the perspective of both diplomacy and academic study is its incorporation of an administrative approach to liability for biodiversity damage, rather than a fully fledged civil liability regime. Three chapters examine the prelude to, the negotiation over and the legal significance of this core feature of the Supplementary Protocol that underlies all other issues examined in this book.

This book is composed of three parts. Part I addresses the international legal context and the negotiating history underlying the Supplementary Protocol. In Chapter 2 (‘A new dimension in international environmental liability regimes: a prelude to the Supplementary Protocol’), Akiho Shibata, a professor of public international law at Kobe University, Japan, and a legal advisor to the Japanese delegation negotiating the Supplementary Protocol between 2006 and 2010, examines the legal structure of the Supplementary Protocol, and questions whether its conceptual underpinning that lays the foundation of administrative approach to liability has any preludes in general international law (as opposed to US, EU and other domestic practices). After an examination of the discussion in the United Nations International Law Commission (ILC) under the agenda item ‘international liability’, he concludes that the two-tiered structure of the ILC Allocation of Loss Principles adopted in 2006 was the true international law prelude to the administrative approach to liability for environmental damage. As such, he argues that the Supplementary Protocol is firmly grounded on a general theory of liability as accepted by the ILC that bestows it with legitimacy and the power to pull States towards its acceptance.

In Chapter 3 (‘Negotiating the Supplementary Protocol: the Co-Chairs’ perspective), René Lefeber and Jimena Nieto Carrasco, the Co-Chairs of the Ad Hoc Working Group and the Group of Friends of Co-Chairs (GFCC) tasked with negotiating a liability regime under the Cartagena Protocol between 2004 and 2010, examine the history of the six-year negotiations leading to the adoption of the Supplementary Protocol. The Co-Chairs disclose that it was at their initiative that an administrative approach to liability was put on the table as one option among several approaches to liability. Further, they note that they had to resort to innovative initiatives and techniques such as ‘Blueprint’ and ‘Core Elements Paper’ to expedite the negotiations and the ‘confessionals’ to comprehend the bottom lines of the delegations’ instructions. They also endeavoured to engage the civil society and business representatives in the negotiation, while effectively employing both behind-the-scenes bilateral talks with the recalcitrant parties and, occasionally, closed meetings of the GFCC. Now, they seek t...