![]()

The kind of language found in public spaces plays a significant role as a barometer of language ideologies and can function over time as an indicator of social transformations. This special issue of Japanese Studies examines an aspect of linguistic life that is also attracting scholarly attention in many other countries where globalisation has led to growing multilingualism and where rapidly advancing new media technologies are seen as increasingly influencing language use: namely, the varieties of language use encountered in public spaces that highlight underlying social developments shaping the directions in which many contemporary societies are moving. Using the lens of language encountered in public spaces, we aim to provide a deeper understanding of the sociolinguistic currents shaping language use in Japan today by examining multifaceted aspects of linguistic diversity, both in terms of the use of languages other than Japanese and of the varying manifestations of the Japanese language itself.

A large proportion of the existing research literature on language in Japan deals with the use of language in private contexts. This issue’s theme of language in public spaces has therefore been chosen in order to shift the focus from the personal to the public. At the same time, however, some of the articles (Gottlieb, Occhi et al.) highlight the use of the personal within the public spaces of media and the Internet, illustrating the place of the private within a public or semi-public sphere. The term ‘public spaces’ is here conceptualised as including cyberspace in addition to the physical environment of public spaces through which people move; over the last decade a growing body of research has emerged around the use of the Japanese language on computers and the Internet. At the same time, recent scholarly interest in the physical details of the linguistic landscape has resulted in a seminal book by Backhaus on street signs in Tokyo as indicators of the management of emergent multilingualism. The public spaces covered in this issue therefore range from the material (an international airport, the streets of Tokyo, the JSL classroom in Japan) to the electronic (television dramas, local government web pages and cyberspace).

One of the major uses of language in public space is, of course, on signs. Using a narrative theory approach, Wetzel examines advertising and informational public signs, focusing on their relationship to the reader and on notions of language as praxis. The narrative approach, she concludes, enables an understanding of how particular ends are achieved in Japanese culture and of what kind of ends are being sought through such signs. Backhaus also investigates public signs, this time multilingual ones in Tokyo: basing his study on the methodology of the relatively recent linguistic landscaping subfield of sociolinguistics, he shows how they can be read as indicative of wider changes in Japanese society and its overall linguistic makeup. Heinrich, using a linguistic ecology approach, investigates language choices on signs at Naha Airport in Okinawa, arguing that they perpetuate an entrenched nationalist language ideology and suggesting ways in which the language ecology of a public space such as the airport could be changed to avoid this.

When we define cyberspace and electronic media as public spaces of a different kind, then we find interesting issues of language use in evidence here as well. Many local governments make proactive use of multilingual websites for the benefit of foreign residents in their areas: Carroll’s paper investigates the use of languages other than Japanese on prefectural websites, taking several as case studies and in the process raising some interesting points about language policy and e-government. Within the Japanese language itself, the language of cell phone emails, chatrooms and bulletin boards continues to diversify and to generate seemingly new forms of language use. My own article, however, from the theoretical standpoint of language play, argues that orthographic play found in cyberspace – far from being a revolutionary or even evolutionary new development – is simply the continuation of a long tradition which can be traced back to the earliest days of written Japanese and has now been moved into the much wider public arena of cyberspace. And finally in this bracket of articles, Occhi, SturtzSreetharan and Shibamoto-Smith examine men’s language use in romantic dramas, focusing on the link between the romantic hero, Standard Japanese masculine forms and dialect in popular television dramas: ‘the language practices of Mr Right in romantic representational contexts’, under the rubric of television as a broader cultural ideology of space.

The articles by Thomson and then Nakane consider language use in two highly interactive public spaces: the JSL classroom in Japan itself and the Japanese courtroom. Thomson adopts a Second Language Acquisition perspective in her examination of the effect of the idea that there is only one correct form of Japanese on the lives of learners of Japanese as a second language within Japan, both inside the classroom where textbooks and teachers model correctness and outside it where learners are constantly subjected to the judgment of native speakers about the correctness of their Japanese. And finally, Nakane uses Halliday’s systemic functional linguistics framework to investigate an important linguistic aspect of Japanese courtroom practice, namely which stages of trials are interpreted and which are conducted in Japanese only, warning against a simplistic view of register which assumes that ostensibly non-technical questioning of defendants does not require interpreting.

While the articles in this issue thus feature a variety of theoretical approaches, coherence has been assured by their intellectual contribution to discussion of the overarching theme of language in public spaces. I would like to thank all contributors for their thought-provoking articles and for their cooperation and patience during the process of putting the issue together. And of course, I offer my sincere thanks to Judith Snodgrass for her enthusiastic support for both the initial idea and the ongoing development of this issue, and to David Kelly for his patient and scrupulous editing.

Nanette Gottlieb

University of Queensland

![]()

PATRICIA J. WETZEL, Portland State University, USA

Public signs (both advertising and informational) are analyzed here as narrative. This allows us to see the parallels between abbreviated texts in public spaces and extended discourse that has a long history of analysis. It also reveals parallels between literary and linguistic treatment of discourse. Included in the analysis is a description of how reference and indexicality function in the discourse we see all around us on what might be called ‘the linguistic landscape’, as well as how point of view operations, focalization, and voice are manipulated to authors’ specific ends.

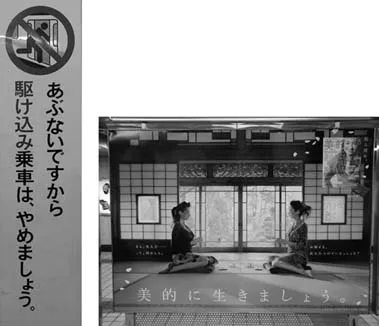

The landscape of Japan – especially urban Japan – is filled with voices that clamor for our attention (see Figure 1). The layers of pure advertising, the common exhortations to stop smoking and running onto trains, the cautions to watch for pickpockets and other ne’er-do-wells, the prohibitions against parking and littering – all of these tell a complex and cacophonous story.

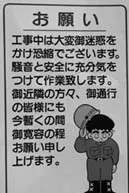

It is possible to take a formalist stance and examine how the linguistic elements of these signs operate. For example, construction sites in Japan almost always post an apology that is filled with honorific language that expresses regret on the part of the builder for any inconvenience that might be visited on the passers-by (see Figure 2). Another commonly observed formal feature of Japanese signs and advertisements is that they are much more likely to use a hortative (-mashō, ‘let’s’) than an imperative form (as might be expected in an English sign) to elicit behavior or consumption from readers (see Figures 3 and 4). This even extends to cannibalizing English morphology such as ‘Let’s’ to get readers to patronize a company (see Figure 5).1

Such analysis of the linguistic forms that are associated with speech acts gives insight into the pragmatic use of language – the manipulation of form within context to achieve certain ends. But it does not tell us about the relationship of the sign to the end user: the reader. As a sojourner in Japan, I often find myself being drawn into these signs, and asking, ‘Who are the people in these signs to me? And who am I to them?’ What I propose to do here is to look at these signs in terms of narrative – to examine their relationship to the reader and to notions of language as praxis.

FIGURE 1. The landscape of urban Japan is cluttered with signs that include advertisements (on the left) and admonitions against parking and/or walking (on the right).

FIGURE 2. Apology to people affected by construction. ‘Please. [We] regret (humble) that [we] are causing a terrible nuisance (polite) while under construction. [We] will carry out (humble) [our] work being careful to pay sufficient attention to noise and safety. For the time being, [we] request (humble) the tolerance (polite) of people (polite) in the neighborhood (polite) and everyone (polite) who passes through in transit (polite).’

Signs as Narrative

Public signs are seen here as mini-narratives. The use of the word ‘narrative’ is intended to establish a parallel between signs and longer discourse (conventional narrative) that has been explored in some depth. Narrative has captured the imagination of many who wish to explore communication and communicative acts that tie into cultural imagination. In this sense, narrative has been variously portrayed as a cognitive artifact, a resource for sense-making (i.e. in therapeutic discourse or recovery from trauma), a text type, a tool for thinking, and a heuristic for judgment.2 Such broad interpretations no doubt owe much to the work of Barthes who expanded the field of narrative when he observed, ‘There are countless forms of narrative in the world … Among the vehicles of narrative are articulated language, whether oral or written, pictures, still or moving, gestures, and an ordered mixture of all these substances … it is present at all times, in all places, in all societies’.3 Psychologists find the notion of narrative useful in analyzing how humans process information, encode and retrieve information, and form cognitive categories. Thus characterized, whether they are about prohibited behavior, the inconvenience of construction, directions for public transportation, or advertisements for goods and services, the signs under discussion here qualify as narratives. They give us access to a story, and in doing so they evoke voices with which the reader is expected to have some familiarity and/or some relationship.

FIGURE 3. Japanese signs that use a hortative (-mashō ‘let’s’). On the left, discouraging train users from running on the platform and into the train, ‘[It]’s dangerous so let’s stop galloping onto the train.’ ...