![]()

1 | THE DISTRIBUTIVE INDUSTRIES AND POST-INDUSTRIAL SOCIETY |

Economies of high mass consumption are now well established in Western Europe. Although pockets of economic and social deprivation exist in the EEC, the pervading life-style of the early 1980s, despite economic recession, is one of affluence compared with thirty years ago. This standard of living is the culmination of continued economic growth of industrial society, together with the creation of economic institutions which distribute the manufactured products. Increasingly, social and political scientists have been questioning both the feasibility and morality of continued economic growth along these now traditional lines. The delivery of the higher standards of living, made possible by industrial growth and expected by the consumer, has been the responsibility of various branches of marketing. It is perhaps somewhat paradoxical that the activities of marketing, which have been instrumental in delivering the goods, never have been criticised and questioned so much as now. Webster (1974), writing of the USA but with obvious application to Europe, develops this paradox to suggest that affluence has bred discontent and has led consumers to question the morality of some marketing practices. Webster points to marketing itself as the generator of the consumerism movement which wishes to restrict some of the activities which gave it birth.

1.1 The Emergence of Post-industrial Society

The change in social values typified by the consumerism movement is seen by other social scientists as part of a broader change in society and a swing from an industrial to a post-industrial economy. Dahrendorf (1975) suggests that the central theme of current social and economic change, ‘is no longer expansion but what I shall call self improvement, qualitative rather than quantitative development’ (p. 14). Bell (1974), Dahrendorf (1975), Rostow (1977) and others, even Marx, have viewed social change as a steady progression through a series of stages with various countries, at any one time, at particular points along the sequence. Rostow’s simplistic sequence from ‘traditional’ state to ‘high mass consumption’ encompasses the urbanisation and industrialisation of society, but he is unwilling to consider the stage beyond mass affluence except in so far as to suggest, tentatively, that the personal goal of durable-goods ownership will be tempered by greater demand for services. Such a view of the shift in consumption related to increasing income has a long history which goes back even before Engels, who was one of the earliest writers to analyse the process. Bell (1974) takes the progression a stage beyond industrial society to suggest the emergence of ‘post-industrial’ society, based not on energy as in industrial society but on information and where the dominant economic sectors become ‘tertiary’ (transportation), ‘quaternary’ (trade, finance, insurance and real estate) and ‘quinary’ (health, education, research, government and recreation). In the last few years other writers have taken up the themes introduces by Bell.

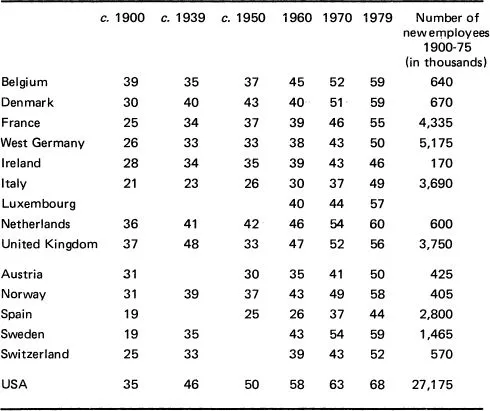

The growth in importance of non-productive activities and the decreasing emphasis on industrially based economic development are not simply theoretical notions of social philosophers. There is firm empirical evidence of the changing structure of the workforce in Western economies and the growth of service industries. Pollard (1979) shows that since 1900 the percentage of service workers in the economies of a sample of Western countries has more than doubled and throughout the EEC service industries employ well over 50 per cent of the workforce. Table 1.1 shows these figures; it must be pointed out that the figures are based on a definition of services by industry sector not by occupation, and that 1977 figures are used since later figures become difficult to interpret because of growing unemployment, particularly in the manufacturing sector. Increasingly, industrial corporations, whose industry sector is manufacturing, contain a large proportion of service workers, so if an occupation-based classification was used the percentages of Table 1.1 would be much higher. Gershuny (1978) points out that for Britain the concentration of service occupations in the manufacturing sector could be a more significant indicator of future social patterns than the more commonly analysed shift in the balance of the industry sectors. Some service industries, Gershuny maintains, are decreasing in importance as changed household activities, allied to higher rates of ownership of consumer durables, encompass traditionally purchased services. Home washing machines, for example, have reduced the demand for specialised clothes cleaning services, and home entertainment has reduced the demand for specialist public entertainment services. The emergence of the self-service economy, he argues, has reduced many personal service industries, but the emergence of large corporations controlling a wide range of economic activities requires the support of industrial service activities. This is also inherent in Mandel’s (1975) analysis of late capitalism, in which he suggests that industrial society is inherently unstable and that capitalism will collapse as capital is transferred from productive to service enterprises. ‘The logic of late capitalism is therefore necessary to convert idle capital into service capital and simultaneously to replace service capital with productive capital, in other words services with commodities’ (p. 406). Mandel argues that this is untenable in a capitalist framework, but by keeping the distinction between service industry and manufacturing industry he fails to appreciate the full interdependencies of what others term post-industrial society. This interdependence is central to the thesis in Galbraith’s (1974) analysis of social change and the emergence of an economy dominated by a service sector and large corporations. In these various theoretical and empirical models it is clear that Western economies are undergoing significant structural change in the late twentieth century and much depends on personal philosophies as to which model is considered acceptable. The effect of this structural change is that increasingly the service sector is being recognised as a leading sector of the economy.

Table 1.1 Employment in Service Industries as a percentage of total Employment

Sources: Pollard (1979) OECD Labour-force statistics.

1.2 The Growth of Service Employment

Gershuny (1978) and others have suggested that the transition from industrial to post-industrial society is characterised by the onset of a decrease in the share of employment accounted for by the industrial sector. The growth of the three commonly identified employment sectors shows considerable variation in rates of change over the past three decades. Generally, the share of the agricultural sector has declined steadily, the share of the tertiary sector, after initial fluctuations, has increased steadily and the share of the industrial sector has increased then levelled off and, in the richer countries, has declined. By the late 1970s the share of the industrial sector in total employment was declining in all the EEC member countries. The early 1960s in the EEC were typified by an increasing share of employment accounted for by the industrial workforce, but this had changed by the early 1970s with, by 1977, post-industrial society well on the way to being established.

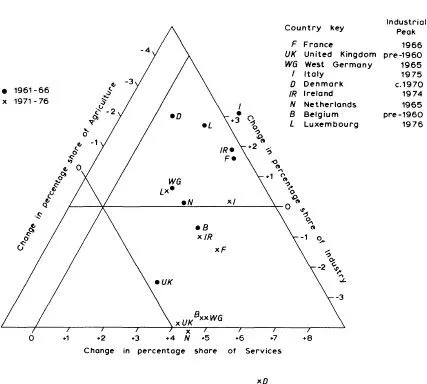

The contrast between the first half of the 1960s and the 1970s is seen in Figure 1.1, where the changes in the percentage shares of the three sectors are plotted for the two time-periods. Between 1961 and 1966 only Belgium and the United Kingdom showed a decline in the percentage share of industry. Ten years later, not only had the rate of decline in both these countries increased but only two countries, Italy and Luxembourg, still showed an increase in the share of their industrial sector and in Italy the industrial share peaked in 1975 and in Luxembourg in the following year. From Figure 1.1 it would appear that the greatest change took place in Denmark. Although this is probably true, it is not quite so dramatic as appears due to a change in the data series in 1969/70 making the earlier figure not directly comparable. The year of the maximum share of the industrial sector is shown in the key on the figure. Although the absolute values of the sector shares vary considerably amongst EEC members and the peak value for the industrial sector ranges from 50 per cent to 33 per cent, none the less the trend of change is similar over all the countries.

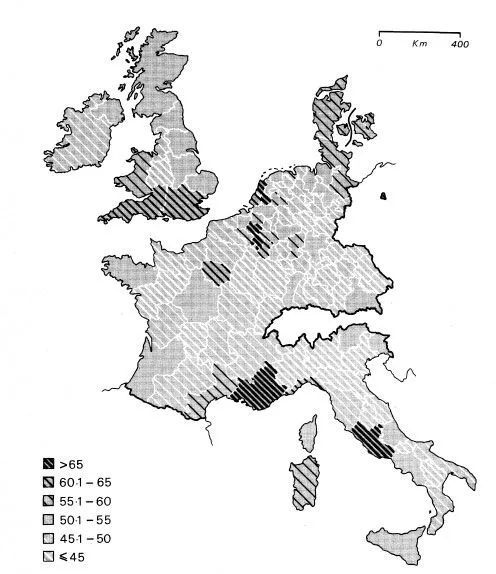

At a regional level there is both greater range in absolute values of sector share and, in 1977, still some regions showing an increase in the share of the industrial sector. The greatest variability in sector share occurs for agriculture; some regions in southern Italy had 30–40 per cent of employment in agriculture in 1977, whereas in north-west Europe figures below 5 per cent were commonplace. Regional differences in the industrial sector are less with the greatest range in France and Italy; rarely did the 1977 percentage fall below 30 per cent or above 50 per cent. The service sector in most regions is the single most important sector and in Provence, Utrecht and Brabant it is responsible for close to 70 per cent of all employment. Figure 1.2 shows the distribution of values over the regions, with low scores not only in regions with a poorly developed infrastructure but also where the industrial sector is still expanding. The overall value for the EEC in 1977 was 52.1 per cent and has since risen both in real terms and also as a percentage of the employed workforce.

Figure 1.1: Change in the percentage Shares of Employment in Agriculture, Industry and Services

Comparisons with the immediate post-war period are possible through the study by Lengelle (1968), which indicated that during the 1950s only two (Saar, Nord) out of the 41 major regions of France, West Germany and Italy showed a decline in the industrial-sector share of employment and all showed a decline in the agricultural-sector share. Between 1970 and 1977 100 out of the 110 regions in the EEC showed a decrease in the industrial-sector share. Of the ten showing an increase three were in the Netherlands and reflect the concerted attempts to attract industrial investment in Zeeland and North Netherlands. There is a considerable range, however, in the change in sector shares with, in several regions, shifts of over 10 percentage points over the 1971–7 period. Changes of this magnitude reflect major adjustments in employment composition. In Lengelle’s study of a ten-year period, mainly in the 1950s, the size of sector change was much less with only six regions showing a shift (increase) of more than 8 per cent in the industrial sector and only one, the Paris region, showing a change of this size in the service sector. The patterns and rate of change are quite different in the early 1970s from the patterns appearing in Lengelle’s study of twenty years previously. The continued growth of the service-sector share of regional employment again reflects the shift from industrial to post-industrial society.

Figure 1.2 Employment Share of Services in EEC Regions in 1977

1.3 The Marketing Revolution in Post-industrial Society

One aspect of this change which has received less attention than others is the extent to which marketing activities have increased their relative power and importance. Almost all the quaternary sector of Bell’s post-industrial society and a significant part of the tertiary sector are dominated by marketing activities. First, the general growth of the service sector has moved large numbers of employees into marketing. Many of the 19 million new jobs in service industries in the EEC since 1900 (shown on Table 1.1) and the increases in service activity in Figure 1.1 and 1.2 are accounted for by marketing activities. Secondly, the change in emphasis to the improvement of the quality of life rather than the pursuit of mass affluence has created new activities and new processes within the marketing economy. This change is more pervasive than the emergence of new values and attitudes amongst consumers, for it also manifests itself in new ideas in industrial marketing and, as Fisk (1976) points out, in a changed attitude to recycling commodities. Thirdly, the conflicts created by the stress inherent in social change have provided government with a new interventionist role in marketing and distribution. Galbraith has analysed the potentials for conflict between the producer and consumer. With governmental realisation of these conflicts, so greater public policy intervention has occurred in the service sector and all aspects of marketing. Public policy traditionally has centred on the productive sections of the economy and the close interrelationship of output and employment. A feature of post-industrial society is the separation of output from employment and consequently the need for a quite different policy approach to managing economic growth and, in turn, social change. As part of this new role government has become a generative force in marketing change while formerly it was passive; however, the acceptance of social responsibilities by marketing agencies also reduces the need for strict governmental control of activity.

The increased rate at which the structure of the macro-economy is changing means that changes in marketing processes are rapid, new technology is quickly developed and applied and even new marketing functions emerge. For many years personal adaptation to marketing change was managed by adaptation within a life-cycle, so that stable marketing processes could be assumed within a single generation with the next generation adapting to the new assumed status quo. A decade ago, Schon (1971, p. 26) argued in the wider context of social change, but the argument is applicable to marketing change that:

Individuals must somehow confront and negotiate, in their own persons, the transformations which used to be handled by generational change. We are no longer able to afford the relatively leisurely process of adaptation which has until now allowed us to keep the illusion of the stable state. (p. 26).

Developments since 1971 only confirm Schon’s view and comparisons of the European surveys of attitudes and goods ownership produced by the Readers Digest Association (1963, 1970) show the transformation that has occurred in Europe in twenty years. Both the form and the rapidity of marketing change has led some workers to term it a marketing revolution.

Undoubtedly revolutionary changes have taken place in marketing and of a magnitude comparable with the industrial revolution of a century and a half ago. Just as the industrial revolution was one aspect of fundamental social change and the onset of industrial society, so the marketing revolution is a small part of the broader process of the emergence of post-industrial society. This association between marketing and social change is a dynamic one. Marketing activities are a causal force in social change and a consequence of social change as well. More strongly, marketing is the instrument of much social change’ (Levy and Zeltman, 1975, p. 45). Such a view is particularly relevant as Western economies move from industrial to post-industrial phases.

1.4 Technique, Organisation and Environment in the Marketing Revolution

It is worthwhile considering, briefly, some of the parallels between the broad changes of the industrial revolution and the general pattern of change currently underway in marketing. Institutional change within the industrial structure of the economy was basic to the nineteenth-century industrial revolution. The techniques and technology of production changed as did the management of the productive processes. Paralleling these are the presently active processes changing marketing technique and organisation. Mass merchandising uses the new retail techniques of the superstore and hypermarket, which are as different from the corner store as the weaver’s cottage was from the woollen mill. Within the new stores the sales techniques have been revolutionised by new technology. Computerised stock-control procedures, a variety of self-service methods on the shop floor, front-end automation with scanners and electronic check-outs which are linked to the stock-control system are all examples of radically new techniques in retailing. Other institutions in the marketing channel have undergone comparable fundamental changes in operating technique. Wholesaling, transport and advertising, for example, are undergoing elemental changes in operating technique just as in the industrial revolution all the activities in the channel of production applied the new technologies to their operational processes.

Patterns of institutional organisation and management changed alongside the techniques of production during the industrial revolution. New management methods and ownership structures emerged to control the productive institutions. Similar patterns are emerging in marketing institutions through processes of vertical and horizontal integration and the rise of multinational marketing companies and conglomerchants. Several retail firms based in the USA operate in Europe and Australia, and European retailers are investing in the USA. This spatial decentralisation is controlled by a much greater decentralisation of corporate power made possible by the new information technologies of post-industrial society. Other management changes are associated with the growth of vertically integrated forms of marketing organisation. At the consumer level there are new and significant changes occurring in the form of organisation. Consumerism is a small but potentially powerful process creating new patterns of consumer behaviour. In Britain, ‘in spite of the development of a consumerist movement and growing government concern with consumer problems, it would be m...