eBook - ePub

World Economic Outlook, April 2016 : Too Slow for Too Long

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

World Economic Outlook, April 2016 : Too Slow for Too Long

About this book

NONE

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access World Economic Outlook, April 2016 : Too Slow for Too Long by International Monetary Fund. Research Dept. in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUNDYear

2016eBook ISBN

9781498398589Chapter 1. Recent Developments and Prospects

Recent Developments and Prospects

Major macroeconomic realignments are affecting prospects differentially across countries and regions. These include the slowdown and rebalancing in China; a further decline in commodity prices, especially for oil, with sizable redistributive consequences across sectors and countries; a related slowdown in investment and trade; and declining capital flows to emerging market and developing economies. These realignments—together with a host of noneconomic factors, including geopolitical tensions and political discord—are generating substantial uncertainty. On the whole, they are consistent with a subdued outlook for the world economy—but risks of much weaker global growth have also risen.

The World Economy in Recent Months

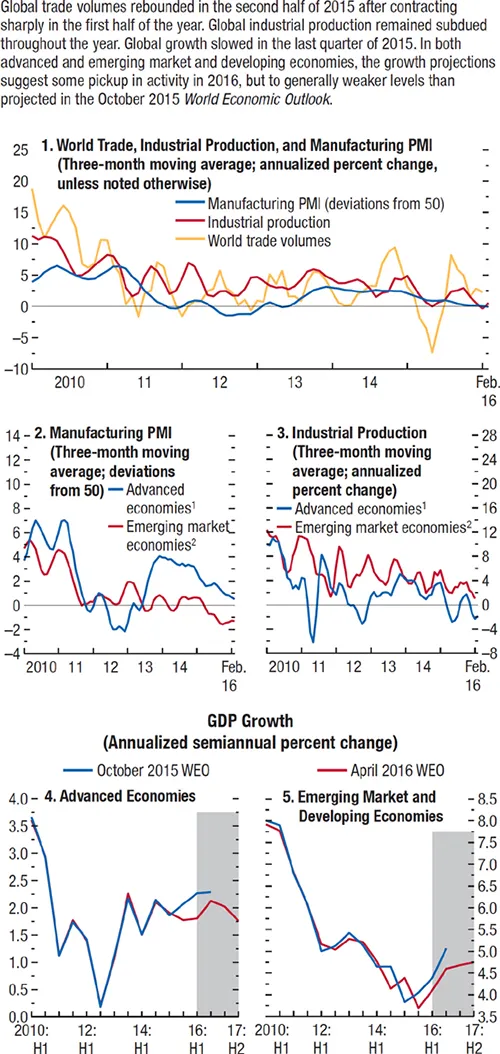

Preliminary data suggest that global growth during the second half of 2015, at 2.8 percent, was weaker than previously forecast, with a sizable slowdown during the last quarter of the year (Figure 1.1). The unexpected weakness in late 2015 reflected to an important extent softer activity in advanced economies—especially in the United States, but also in Japan and other advanced Asian economies. The picture for emerging markets is quite diverse, with high growth rates in China and most of emerging Asia, but severe macroeconomic conditions in Brazil, Russia, and a number of other commodity exporters.

- Growth in the United States fell to 1.4 percent at a seasonally adjusted annual rate in the fourth quarter of 2015. While some of the reasons for this decline—including very weak exports—are likely to prove temporary, final domestic demand was weaker as well, with a decline in nonresidential investment, including outside the energy sector. Despite signs of weakening growth, labor market indicators continued to improve. In particular, employment growth was very strong, labor force participation rebounded, and the unemployment rate continued its downward trend, with a 4.5 percent reading in March.

- The recovery was broadly in line with the January forecast in the euro area, as strengthening domestic demand offset a weaker external impulse. Among countries, growth was weaker than expected in Italy but the recovery was stronger in Spain.

- In Japan, growth came out significantly lower than expected during the fourth quarter, reflecting in particular a sharp drop in private consumption.

- Economic activity in other Asian advanced economies closely integrated with China—such as Hong Kong Special Administrative Region and Taiwan Province of China—weakened sharply during the first half of 2015, owing in part to steep declines in exports. Activity picked up by less than expected during the second half of the year, as domestic demand remained subdued and the recovery in exports was relatively modest.

- Growth in China was in contrast slightly stronger than previously forecast, reflecting resilient domestic demand, especially consumption. Robust growth in the services sector offset recent weakness in manufacturing activity.

- In Latin America, the downturn in Brazil was deeper than expected, while activity for the remainder of the region was broadly in line with forecasts.

- The recession in Russia in 2015 was broadly in line with expectations, and conditions worsened in most other Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) economies, affected by spillovers from Russia as well as the adverse impact of lower oil prices on net oil-exporting countries.

- Macroeconomic indicators suggest that economic activity in sub-Saharan Africa and the Middle East—for which quarterly GDP series are not broadly available—also fell short of expectations, a result of the drop in oil prices, declines in other commodity prices, and geopolitical and domestic strife in a few countries.

- More generally, geopolitical tensions have been weighing on global growth. Output contractions in three particularly affected countries—Ukraine, Libya, and Yemen, which accounted for about half a percentage point of global GDP in 2013—subtracted 0.1 percentage point from global output during 2014–15.

- Global industrial production, particularly of capital goods, remained subdued throughout 2015. This weakness is consistent with depressed investment worldwide—particularly in energy and mining—as well as the deceleration of China’s manufacturing activity.

Figure 1.1. Global Activity Indicators

Sources: CPB Netherlands Bureau for Economic Policy Analysis; Haver Analytics; Markit Economics; and IMF staff estimates.

Note: IP = industrial production; PMI = purchasing managers’ index.

1Australia, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, euro area, Hong Kong SAR (IP only), Israel, Japan, Korea, New Zealand, Norway (IP only), Singapore, Sweden (IP only), Switzerland, Taiwan Province of China, United Kingdom, United States.

2Argentina (IP only), Brazil, Bulgaria (IP only), Chile (IP only), China, Colombia (IP only), Hungary, India, Indonesia, Latvia (IP only), Lithuania (IP only), Malaysia (IP only), Mexico, Pakistan (IP only), Peru (IP only), Philippines (IP only), Poland, Romania (IP only), Russia, South Africa, Thailand (IP only), Turkey, Ukraine (IP only), Venezuela (IP only).

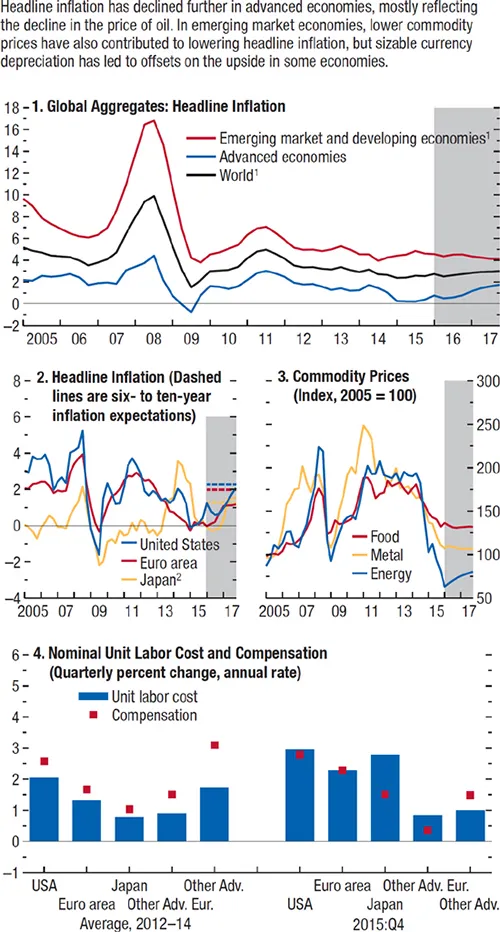

Low Inflation

Headline inflation in advanced economies in 2015, at 0.3 percent on average, was the lowest since the global financial crisis, mostly reflecting the sharp decline in commodity prices, with a pickup in the late part of 2015 (Figure 1.2). Core inflation remained broadly stable at 1.6–1.7 percent but was still well below central bank targets. In many emerging markets, lower prices for oil and other commodities (including food, which has a larger weight in the consumer price indices of emerging market and developing economies) have tended to reduce inflation, but in a number of countries, such as Brazil, Colombia, and Russia, sizable currency depreciations have offset to a large extent the effect of lower commodity prices, and inflation has risen.

Figure 1.2. Global Inflation

(Year-over-year percent change, unless noted otherwise)

Sources: Consensus Economics; IMF, Primary Commodity Price System; and IMF staff estimates.

Note: Other Adv. = other advanced economies; Other Adv. Eur. = other advanced Europe; USA = United States.

1Excludes Venezuela.

2In Japan, the increase in inflation in 2014 reflects, to a large extent, the increase in the consumption tax.

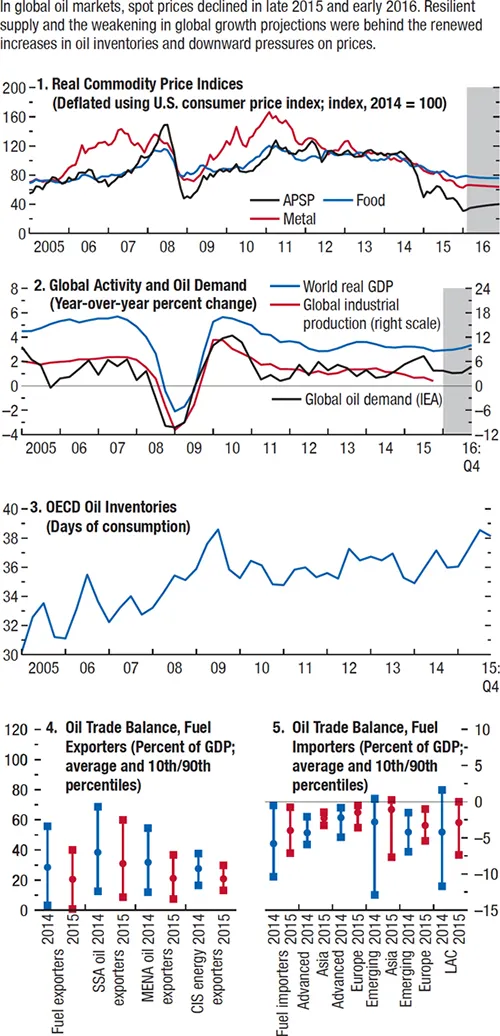

Declining Commodity Prices

Oil prices decreased further by 32 percent between August 2015 and February 2016 (that is, between the reference period for the October World Economic Outlook [WEO] and that for the current WEO report) on account of strong supply from members of the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries and Russia, expectations of higher supply from the Islamic Republic of Iran, and concerns about the resilience of global demand and medium-term growth prospects, as well as risk-off behavior in financial markets, leading investors to move away from commodities as well as stocks (Figure 1.3). Coal and natural gas prices also declined, as the latter are linked to oil prices, including through oil-indexed contract prices. Nonfuel commodity prices weakened as well, with metal and agricultural commodities prices declining by 9 percent and 4 percent, respectively. Excess oil supply pushed inventory levels in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries to record-high levels despite the strong oil demand that much lower prices spurred in 2015.1 Oil prices recovered some ground in March, on the back of improved financial market sentiment.

Figure 1.3. Commodity and Oil Markets

Sources: IMF, Primary Commodity Price System; International Energy Agency (IEA); Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD); and IMF staff estimates.

Note: APSP = average petroleum spot price; CIS = Commonwealth of Independent States; LAC = Latin America and the Caribbean; MENA = Middle East and North Africa; SSA = sub-Saharan Africa.

Exchange Rates and Capital Flows

Between August 2015 and February 2016, the currencies of advanced economies tended to strengthen, and those of commodity exporters with floating exchange rates—especially oil-exporting countries—tended to weaken further (Figure 1.4, blue bars).

Across advanced economies, the Japanese yen’s appreciation (about 10 percent in real effective terms) was particularly sharp, while the U.S. dollar and the euro strengthened by about 3 percent and 2 percent, respectively. In contrast, the British pound depreciated by 7 percent, driven by expectations of a later normalization of monetary policy in the United Kingdom and concerns about a potential exit from the European Union.

Among emerging market economies, depreciations were particularly sharp in South Africa, Mexico, Russia, and Colombia. The Chinese renminbi depreciated by about 2 percent, while the Indian rupee remained broadly stable.

Since February, the currencies of commodity-exporting advanced and emerging market economies have generally rebounded, reflecting a decline in global risk aversion and some recovery in commodity prices (Figure 1.4, red bars). Conversely, the dollar has depreciated by about 1½ percent and the euro by about 1 percent.

The decline in demand for emerging market assets was also reflected in a slowdown in capital inflows, as discussed extensively in Chapter 2. This decline was particularly steep during the second half of 2015, with net sales by foreign investors of portfolio holdings in emerging markets for the first time since the global financial crisis (Figure 1.5). Balance of payments developments in China loom large in explaining the dynamics of aggregate flows to and from emerging markets during this period. Motivated by changing expectations about the renminbi/dollar exchange rate since last summer, Chinese corporations undertook substantial repayments of dollar-denominated external debt (generating negative capital inflows), while Chinese residents increased their acquisitions of foreign assets (boosting capital outflows). With a tightly managed exchange r...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Assumptions and Conventions

- Further Information and Data

- Preface

- Foreword

- Executive Summary

- Chapter 1. Recent Developments and Prospects

- Chapter 2. Understanding the Slowdown in Capital Flows to Emerging Markets

- Chapter 3. Time for a Supply-Side Boost? Macroeconomic Effects of Labor and Product Market Reforms in Advanced Economies

- Statistical Appendix

- World Economic Outlook, Selected Topics

- IMF Executive Board Discussion of the Outlook, March 2016

- Tables

- Footnotes