eBook - ePub

China : Economic Reform and Macroeconomic Management

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

China : Economic Reform and Macroeconomic Management

About this book

NONE

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access China : Economic Reform and Macroeconomic Management by Gyorgy Szapary, Steven Dunaway, David Burton, and Mario Bléjer in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

INTERNATIONAL MONETARY FUNDYear

1991eBook ISBN

9781557752024III Monetary and Fiscal Policies in Transition

Since market-oriented reforms were set in motion in 1978, the nature and role of macroeconomic policy instruments, particularly monetary and fiscal policy, have been transformed pari passu with the changes in the economic system. As discussed in Chapter II, under the rigid central planning in place before the reforms, enterprises had little or no independent decision-making powers with respect to investment, production, prices, or wages, all of which were basically decided by the planning authority. In this setting, the role of monetary policy was essentially to support the implementation of the physical output targets contained in the plan, while preventing an excessive accumulation of liquidity in the household sector. At the same time, the objective of fiscal policy was limited to the administrative allocation of resources by regulating the rate of capital accumulation and maintaining household incomes at a level consistent with the availability of consumer goods.

As the scope of central planning has diminished and agents have been increasingly guided by market signals, macroeconomic management has required adoption of a consistent set of new, indirect, policy instruments. Such instruments have in fact been created, but difficulties in applying them have arisen from a number of factors. First, the pre-existing techniques and institutions of central planning have been allowed to continue functioning alongside the new ones. Second, the decentralization of economic decision making to economic agents has been interpreted as requiring also a considerable degree of decentralization of economic management from the central government to lower levels. The increasingly powerful role played in the economy by local governments at the provincial, city, and county levels, which see their primary role as supporting the development of their own regions, has severely affected the ability of the central government effectively to utilize the new indirect instruments to maintain macro-economic balance. These fundamental problems have exacerbated the technical difficulties inherent in developing instruments of macroeconomic control suited to the new environment, and periods of inflation or external imbalance have resulted.

The following sections examine the evolution of the roles of monetary and fiscal policies as the reforms have proceeded. They also consider whether there are characteristics of the reform process that inhibit the maintenance of control over aggregate demand, and explore the question of how firm macroeconomic control can be maintained in a partially reformed economic system without resort to policies that negate the basic intent of the reforms.

Monetary Policy

In the economic system that emerged during the 1980s, monetary policy came to play an independent and major role in macroeconomic management. With more financial resources left in the hands of enterprises and households, and with greater freedom of choice over how these resources should be used, money was no longer just a counterpart to physical transactions specified in the plan, but was also important as a store of value and as a medium of exchange for coordinating unplanned market transactions. The expansion in the role of the financial system was also reflected in the increase in the proportion of enterprise investment financed by the banking system. At the same time, price and trade liberalization increased the potential for expansionary monetary policy to be reflected in inflation and external imbalances.

Policy Formulation and Implementation

Prior to the reforms, monetary policy was implemented through a credit plan and a cash plan. The credit plan was the financial counterpart of the physical plan and specified the amount of credit needed by enterprises to implement the output targets. Enterprises were not allowed to hold cash and their holdings of financial assets were closely regulated (the dual payments system). Enterprises were required to remit all their surplus funds to the Government, and in turn the budget supplied the funds for investment. Bank credit was used chiefly to provide working capital and was related to the accumulation of inventories by enterprises. The cash plan covered the various factors that influenced the amount of cash in the economy, principally the payment of wages and the purchase of agricultural products. However, the PBC had little control over most of the factors affecting the amount of currency in circulation, and its role was essentially to monitor cash flows and alert the authorities when deviations from the cash plan occurred. Since most prices, foreign trade, and external capital flows were controlled prior to the reforms, an excess supply of money generally had little impact on prices or the balance of payments but was rather reflected in shortages in the goods market. Given the “soft” budget constraints under which enterprises operated—a characteristic of which was an accommodating credit policy37—the system tended to generate excessive liquidity in the economy which was reflected in the rationing of goods and the accumulation of forced savings. On occasion, however, these pressures were allowed to be passed on to higher prices, such as in 1961 when recorded inflation rose to 16 percent.

In response to the evolving role of monetary policy, there have been major changes in the formulation and implementation of monetary policy since 1979.38 Although the annual credit plan continues to be a central element in the formulation of monetary policy,39 banks have been given greater discretion with respect to loans for working capital.40 A cash plan is also still a part of the policy formulation process, but the target for the increase in currency is now only indicative.41 Also, while the formulation of the credit plan remains essentially a “bottom up” exercise that focuses on the credit needs of borrowers, the PBC has recently begun to evaluate the credit plan in the context of a broader financial program. The latter is based on objectives for economic growth and inflation and includes targets for broad money as well as for currency.

Reflecting the coexistence of planning controls and market mechanisms in China, monetary policy is implemented through what may be viewed as a dual control system that relies on both direct credit controls and indirect levers. Under the credit plan, credit ceilings are established for each specialized and universal bank,42 and the banks, in turn, allocate ceilings to their local branches.43 The extent to which credit ceilings have been enforced, however, has varied considerably in recent years. At times they have been little more than indicative targets, and in some years, reflecting weak enforcement, they have been substantially overshot. On other occasions, particularly when monetary policy was being tightened, credit ceilings have been enforced more strictly. On these occasions the authorities have reemphasized controls over credit allocation to sectors and specific enterprises to ensure that credit went to areas deemed to be of priority, so that the brunt of the credit restraint was borne by nonstate-owned industries.44

Efforts were made in the second half of the 1980s to place greater reliance on indirect instruments of monetary control, especially reserve requirements, interest rates, and PBC lending to banks—as opposed to credit ceilings—in controlling the overall amount of credit. The PBC’s ability to control bank credit indirectly, however, has been limited by the ability of local governments to put pressure on its own branches to extend credit to banks to enable them to meet regional credit needs. As a result, growth in PBC credit to banks itself has at times been a major cause of rapid monetary expansion. Steps were taken during 1987–88 to strengthen PBC head office control over the lending by its branches by giving new loans under the plan a fixed maturity and by placing restrictions on the ability of local branches to extend temporary credits. Subsequently, in 1989, a requirement that the appointment of presidents of branches be approved by head office was introduced, and measures were taken to ensure that short-term PBC credits are withdrawn when they fall due.

With regard to interest rates, which are regulated by the PBC, adjustments were infrequent until 1988 despite sizable fluctuations in the inflation rate. The rigidity of interest rates reflected, in part, concern about the impact of increases in lending rates on enterprises whose profitability was restricted by price controls. Since then, interest rates have been adjusted on several occasions, and the interest rate on long-term savings deposits has been linked to inflation.45 In addition, financial institutions have been given limited flexibility to set interest rates higher than those specified by the PBC.

At the present transitional stage of reform, interest rates appear to be more effective in influencing the demand for deposits than in affecting either the demand for, or, in particular, the allocation of credit. Households are natural optimizing units that face rigid budget constraints, making them sensitive to the returns on financial instruments. This responsiveness was illustrated by the effectiveness of increases in deposit rates in halting a run on deposits during the summer of 1988. By contrast, many state enterprises, especially those that are unprofitable, continue not to be fully responsible for their financial performance and are frequently able to obtain subsidies to cover losses. Hence, their demand for credit may not be strongly influenced by the cost of borrowing.46 The impact of changes in lending rates on credit demand by nonstate enterprises, which account for a growing proportion of economic activity and have to operate within relatively hard budget constraints, is likely to be greater than for the state sector. Nevertheless, the allocation of credit remains determined by the credit plan and local interventions rather than by market mechanisms, and nonstate enterprises have borne the brunt of efforts to ration credit supply.

Monetary Developments

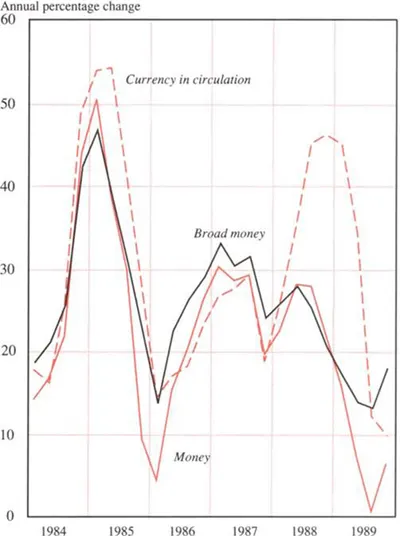

Difficulties in maintaining monetary control under the reforms have been reflected in wide fluctuations in the growth rates of money and credit aggregates (Chart 1 and Table 1). In late 1984 and early 1985, for example, the rate of monetary expansion increased dramatically as the in-creased financial autonomy granted to enterprises led to a sharp increase in the demand for credit to finance investment and wage bonuses that the newly established central bank was not yet strong enough to resist.47

Chart 1. Monetary Developments, 1984–89

(Annual percentage change)

Source: Data provided by the Chinese authorities.

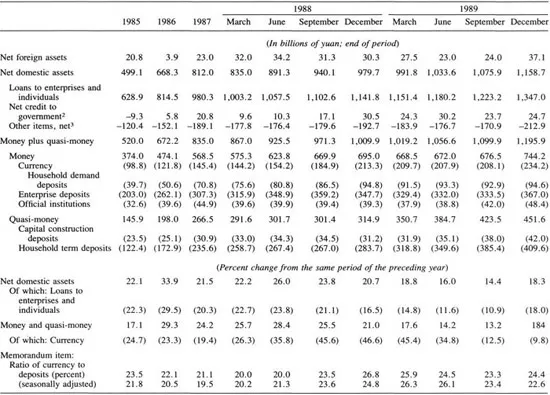

Table 1. Monetary Survey, 1985–891

Sources: People’s Bank of China; and staff estimates

1 Covers the operations of the People’s Bank, the four specialized banks, the two universal banks, and the rural credit cooperatives.

2 Claims related to the state budget operations less government deposits, which include extrabudgetary deposits of local governments.

3 Includes financial bonds issued by banks.

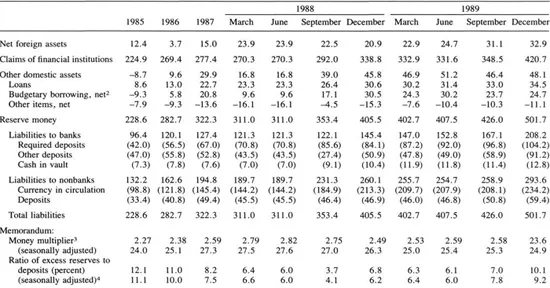

As inflation rose in mid-1985, the PBC took steps to tighten policy, particularly through stricter enforcement of credit ceilings, and money and credit growth rates slowed sharply. Subsequently, concerns about a slowdown in economic growth led to an easing of policy that resulted in broad money growth rates close to 30 percent for much of 1987 and the first three quarters of 1988.48,49 Interestingly, the broad money expansion during this period was fueled not so much by PBC credit to banks as by a large drawdown of banks’ excess reserves (Table 2). The utilization of these excess reserves was made possible by a shift from mandatory to indicative ceilings on banks’ loan portfolios in 1987; it was facilitated by the development of an interbank market that allowed banks to economize on working balances.

Table 2. Operations of the People’s Bank of China, 1985–891

(In billions of yuan; end of period)

Sources: People’s Bank of China; and staff estimates

1 Ba...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- I. Introduction

- II. Overview of Reforms

- III. Monetary and Fiscal Policies in Transition

- Appendix: Demand for Money

- References

- Tables

- Footnotes