eBook - ePub

International Trade and Economic Growth (Collected Works of Harry Johnson)

Studies in Pure Theory

Harry G. Johnson

This is a test

Share book

- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

International Trade and Economic Growth (Collected Works of Harry Johnson)

Studies in Pure Theory

Harry G. Johnson

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The studies collected in this volume embody the results of research conducted in the mid 1950s into various theoretical problems in international economics. They fall into three groups – comparative cost theory, trade and growth and balance of payments theory. This volume consolidates the work of previous theorists and applies mathematically-based logical analysis to theoretical problems of economic policy.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is International Trade and Economic Growth (Collected Works of Harry Johnson) an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access International Trade and Economic Growth (Collected Works of Harry Johnson) by Harry G. Johnson in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Volkswirtschaftslehre & Wirtschaftstheorie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

COMPARATIVE COST THEORY

CHAPTER I

Factor Endowments, International Trade and Factor Prices*

IN the past few years, there has been a revival of interest in the Heckscher-Ohlin model of international trade, and a closer scrutiny of two propositions associated with its analysis of the principle of comparative costs.1 The first is that the cause of international trade is to be found largely in differences between the factor-endowments of different countries; the second that the effect of international trade is to tend to equalize factor prices as between countries, thus serving to some extent as a substitute for mobility of factors. The result, very briefly, has been to show that neither proposition is generally true, the validity of both depending on certain factual assumptions about either the nature of technology or the range of variation of factor endowments which are additional to, and much more restrictive than, the assumptions of the Heckscher-Ohlin model itself.

My purpose here is to survey the related problems of the relation between factor-endowment and international trade and the effect of trade on relative factor prices, with the aim of clarifying the nature and simplifying the explanation of some of the results of recent theoretical research. The main instrument employed to this end is a diagrammatic representation of the technological side of the economy, developed from one originated by Mr R. F. Harrod.2

In common with other models of international trade, it is assumed, on the consumption side, that tastes and the distribution of the means of satisfying wants (property ownership, or claims on the social dividend) are given; and that, on the production side, technology and the supply of factors of production in each country are given (the latter implying that factors are immobile between countries). Production functions and factors are assumed to be identical in all countries; the outputs of goods are assumed to depend only on inputs of factors into the production processes for those goods, and factors are assumed to be indifferent between uses. Further, production is assumed to be subject to constant returns to scale, so that the marginal productivities of factors depend only on the ratios in which they are used. Finally, perfect competition and the absence of trade barriers (tariffs and transport costs) are assumed. The argument is simplified still further by assuming, initially, the existence of only two countries, I and II, two goods, X and Y, and two factors of production, labour and capital,3 the available quantities of the factors being given independently of their prices.

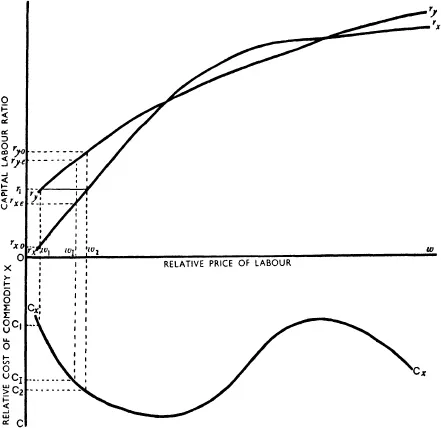

The given technical possibilities of production, summarized in the production functions, imply a definite relationship between the optimum capital: labour ratios in the two industries, relative factor prices, and relative costs of production of commodities. This relationship is represented in Fig. 1. For any given relative price of labour in terms of capital (such as wI) there will be an optimum ratio of capital to labour in the production of each good (rx.e in X and ry.e in Y) which equates marginal productivities to factor prices, and a relative cost of X in terms of Y (cI) which embodies the ratio of their costs of production at the given factor prices with the associated capital: labour ratios.

An increase in the relative price of labour above the given level will make it profitable to substitute capital for labour in both industries, thus raising the optimum capital: labour ratio in both;4 it will also increase the relative cost of the labour-intensive good (X in the neighbourhood of wI), since its costs will be raised more than those of the capital-intensive good by the increase in the relative price of labour.5 Further increases in the relative price of labour will continue to raise the optimum capital: labour ratio in both industries; but either one of two possibilities may be the effect on the relative cost ratio, depending on the relative ease of substituting capital for labour in the two lines of production. The first, and simpler, occurs when one commodity remains labour-intensive and the other capital-intensive, whatever the relative factor price. In this case, one commodity can be definitely identified as labour-intensive and the other as capital-intensive; and the relative cost of the labour-intensive good will continue to rise as the relative price of labour rises, so that the latter can be deduced from the former. The second occurs when, owing to greater facility in substituting capital for labour in the initially labour-intensive good, the difference in capital-intensity between the two goods narrows and eventually reverses itself, so that the labour-intensive good becomes capital-intensive and vice versa; such a reversal of factor-intensities may occur more than once (as illustrated in Fig. 1), as variation in relative factor prices induces variation in the capital-intensity of production of both goods. In this case, a commodity can only be identified as labour-intensive or capital-intensive with reference to a range of relative factor-prices or (what is the same thing) a range of capital-intensities; and the relative cost of a commodity will alternately rise and fall as the relative price of labour rises, as that commodity varies from being labour-intensive to being capital-intensive. Consequently more than one factor price ratio may correspond to a given commodity cost ratio, and the factor price ratio cannot be deduced from the commodity cost ratio alone. The distinction between the two cases, which turns on the facts of technology, is fundamental to what follows.

FIG. 1

The analysis so far has been concerned with the relationships implicit in the given technological possibilities of production. But only a limited range of the techniques available can actually be used efficiently by a particular economy with a given factor endowment; and the possible range of relative factor prices and relative commodity costs is correspondingly limited. The factor endowment of the economy sets an overall capital: labour ratio, to which the capital: labour ratios in the two industries, weighted by the proportions of the total labour force employed, must average out. At the extremes, the economy’s resources may be used entirely in the capital-intensive industry or entirely in the labour-intensive industry; and the relative prices of factors, and the relative costs of commodities, must lie within the limits set by these two extremes.6

The restrictions imposed by the factor endowment on the techniques the economy can employ and on the possible variation of factor prices and relative costs of production are illustrated in Fig. 1, where rI represents the economy’s overall capital: labour ratio. If all resources are used in the production of Y, the relative price of labour will be w1, if all are used in the production of X the relative labour price will be w2; the corresponding relative costs of commodity X are c1 and c2. As w rises from w1 to w2, the capital: labour ratio in Y rises from rI to ry.o and the ratio in X from rx.o to rI; the increases in these ratios are reconciled with the constancy of the overall capital: labour ratio by a shifting of resources from production of Y to production of X, which frees the capital required for the increases in the ratios. It can easily be shown that, for any relative factor price, the proportions of the total labour supply employed in one of the industries is equal to the ratio of th...