eBook - ePub

Urban Decline (Routledge Revivals)

David Clark

This is a test

Share book

- 162 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Urban Decline (Routledge Revivals)

David Clark

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

In the twentieth century, urban growth was one of the most powerful catalysts of geographical, social and demographic change in the Western world. When this book was first published in 1989, however, a massive process of counter-urbanization was underway, which saw the loss of population and jobs in cities and a pronounced urban to rural shift. This book analyses the causes and consequences of urban decline in Britain and the developed world during this period and beyond, and assesses the implications for urban planning and policy. David Clark's relevant and comprehensive title will be of value to students with a particular interest in urban geography and development.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Urban Decline (Routledge Revivals) an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Urban Decline (Routledge Revivals) by David Clark in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Human Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter one

Urban depopulation

British cities are in decline. Population levels are falling, the industrial base is shrinking, and the governmental and financial powers and autonomy of the city are being eroded. The symptoms and consequences of this decline are the focus of daily attention, analysis and prescription in local and national news media. Inner urban decay, crime, racial tension, riots, mass unemployment and falling standards of service provision are some of the more obvious and disturbing indicators of a general and deep-seated deterioration in the social, economic, political and financial fabric of the city.

For all its contemporary severity, urban decline is a comparatively recent phenomenon. Thirty years ago, maps of population trends were confirming the continuation of a pattern of national population change that had been established in the late eighteenth century. Growth was occurring in all the major cities, as it had since the beginning of the industrial revolution, as natural increases of the urban population were compounded by net in-migration. Conversely, extensive tracts of rural Britain were losing population as people left the farm and the village for the city. Today, these patterns are the reverse. Urban population levels are falling as more are lost from the city by net out-migration than are gained through the excess of births over deaths. Far from being centres of attraction, cities have become zones of abandonment. It is at the fringe of the city-region and beyond that growth is occurring. The most dynamic parts of the urban system are small towns and market centres in the rural periphery; precisely those places and areas that were stagnating and declining at mid-century.

Employment levels in the city have shown a similar pattern of change. Following a steady if unspectacular rise over the immediate post-war period, the numbers of jobs in British cities have fallen sharply. Within this overall pattern, the change in the number and location of manufacturing jobs has been most pronounced and has had the most far-reaching consequences. As a result of the growth of mass production from the First World War onwards, the major cities became the principal manufacturing centres of Britain. Although there was some shift of production jobs from urban to rural areas in the 1960s this was primarily the product of differential rates of growth. The massive de-industrialization of the UK economy since 1966, the peak year for manufacturing employment has, however, been strongly urban centred so that cities have become areas of concentrated employment decline. At the same time, the urban-rural shift has continued because the rate of job loss has been less outside the city.

As well as losing people and jobs, the power of cities as units of local government is in decline. Until the early 1970s, the major British cities enjoyed considerable independence and influence by virtue of their county borough status. They provided a wide range of personal and environmental services and enjoyed a high level of financial autonomy by virtue of their rates income. Today, these powers are much reduced. As a consequence of local government reforms in 1974, and the abolition of the metropolitan counties and the Greater London Council in 1984, cities have been relegated to the position of district authorities. They have lost many responsibilities in the areas of health care, water supply, sewage treatment, transport provision, and planning. Moreover, changes in the structure of local government finance mean that their budgets are now effectively dictated and controlled by central government. Rather than acting as principal pivots in the second tier of government, cities have lost much of their power and identity being subsumed within the unitary centralized state that is increasingly emerging in modern Britain.

Urban decline is not unique to Britain. Cities in many countries throughout the world are experiencing massive and accelerating population and employment loss. The extent and characteristics of its occurrence suggests that decline, measured in social and economic terms, may represent a stage in the long-term evolution and development of the city. By this interpretation, cities first grow as the population of a country concentrates in a small number of large clusters. These then spread outwards locally as central area densities lessen and as growth occurs within the adjacent commuting areas. Urban decline is associated with the deconcentration of the population into small towns and rural areas as part of a general process of counterurbanization. The fact that cities in other countries appear to have evolved through these stages suggests that urban decline is in part attributable to processes of demographic change that are determined by the level of economic development.

While there may be close parallels with experiences elsewhere, the decline of cities as units of local government is a result of circumstances prevailing in Britain. It is a consequence in particular of the centralization of power in the country which has benefited Whitehall at the expense of City Hall. The reason cited by central government is the need to improve the cost effectiveness and accountability of local government and finance. The primary motive however is party political and involves the increased subordination of large city-based municipal socialism by the Right-dominated centre. The existence of these strands underlines the complexities of the processes which are responsible for urban change in contemporary Britain. Long-term and broad-based processes of population and employment decline are being compounded by the actions of central government which, in reducing the power and influence of the city, have undermined the basis of the local state.

The change from urban growth to urban decline means that the relevance of much of established urban policy is brought into question. Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, population and employment statistics were pointing to rates of increase which necessitated the continuation of the urban containment policies of the immediate post-war period. Initiatives as varied as green belt, new towns, prevention of scatter, town development and expanded towns schemes, as well as several aspects of traditional regional policy, were all concerned with constraining, regulating and redirecting urban growth. Indeed the whole orientation of planning at the time was to counter the forces of megalopolitanization which arose out of rising urban populations and employment levels.

This applied not merely to the policies themselves but also to the whole structure of local authority based planning. An anti-urban bias was an inherent feature of local government, urban authorities having neither the powers nor the space with which to tackle their problems of growth and expansion. The reversal in the direction of urban change, however, has given rise to new problems requiring new structures and solutions. The contemporary shortcomings of the city stem from decline rather than growth. Cities are being reshaped and refashioned in ways, and with consequences that were neither envisaged when the bases for urban planning were established in 1947, nor when local government was reformed in 1974. There is an urgent need for planners to recognize the reality of urban decline and to devise policies which attempt to deal with its various consequences.

This book focuses on the anatomy of urban decline. It outlines the causes, characteristics and consequences, and examines the implications of decline for planning and for policy. Central to the argument is the contention that decline is the product of powerful and well established social and economic processes, associated with the stage in the urban life-cycle, which are working against the Western city. Their adverse effects are compounded by the progressive centralization of power in the United Kingdom in recent years which has reduced the ability of cities to respond to change. So deeply entrenched are the processes of decline, however, that the extent to which they can, indeed should be reversed, is questioned. Over twenty years of urban initiatives have produced few tangible benefits to the city. Rather than pursue policies of regeneration which have limited prospects for success, a case is made that the role of planning should be to encourage and to facilitate the decline of redundant cities and to promote the creation of new urban forms, more suited to contemporary needs, elsewhere. These issues are explored systematically in chapters dealing with economic (Chapter 2), governmental (Chapter 3), and financial aspects of decline (Chapter 4). The implications for policy are considered in Chapter 5. Having outlined the salient points of the argument, this chapter focuses in detail upon urban population decline, both internationally, and in the United Kingdom.

Decline in perspective

The experience of urban decline is both new and restricted to particular areas in the world. Although the comparative studies which have been reported are few in number and are limited by the availability of data to a consideration of population trends they show that the replacement of growth by decline is very much a feature of the last twenty years. Evidence for the onset of decline was first highlighted in the United States by Berry (1976). He pointed out that between 1970 and 1973, US metropolitan areas grew more slowly than the nation as a whole and substantially less rapidly than non-metropolitan America. The validity of this observation was quickly confirmed by Beale (1977), McCarthy and Morrison (1977) and Sternleib and Hughes (1977). So significant is this turnaround that it represents, for Vining and Strauss (1977), a ‘clean break’ with the past. By this interpretation, the onset of decline heralds the introduction of a new and fundamentally different era in the history of urban development.

Although it is now widespread, urban decline is by no means universal in occurrence. The incidence of decline varies according to the level of national economic development and the size and stage in the life-cycle of the city. Large Western cities with strong roots in nineteenth-century industrial technology are experiencing the greatest losses, but the pattern of urban population change among smaller centres within the same countries is more varied. Cities in Third World and Eastern Bloc countries, appear as yet to be largely unaffected by decline.

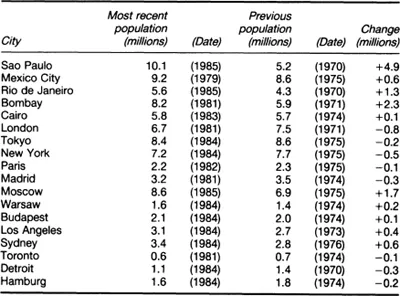

Table 1 Population change in selected cities

Source: United Nations Demographic Yearbooks.

Some very basic evidence to support these generalizations is shown in Table 1. Sao Paulo, Mexico City, Rio de Janeiro, Bombay and Cairo illustrate the scale of population increases that are currently being experienced by major cities as urban growth continues unchecked throughout the Third World. The population of London, New York, Tokyo, Paris and Madrid is, however, falling. Eastern Bloc cities such as Moscow, Warsaw and Budapest are expanding slowly as are some ‘younger’ western cities such as Los Angeles and Sydney. In contrast, Western cities with older roots, such as Toronto, Hamburg and Detroit are in decline.

A more detailed insight into the characteristics of contemporary urban change throughout the world is provided by Vining and Kontuly (1978). They found that a decline in the population of the major urban regions in the most advanced nations has occurred in recent years. Of the seventeen countries for which reliable comparable data were assembled, eleven (Japan, Sweden, Italy, Norway, Denmark, New Zealand, Belgium, France, West Germany, East Germany and The Netherlands) were found in 1978 to be experiencing a decline in the population of their urban core areas. In the first seven of these eleven countries this pattern first became apparent in the 1970s. In the last four, its onset was recorded in the 1960s. The core areas of six countries (Hungary, Finland, Spain, Poland, Taiwan, and South Korea) were still growing in 1978. Even allo...