eBook - ePub

Urban Geography (Routledge Revivals)

An Introductory Guide

David Clark

This is a test

Share book

- 232 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Urban Geography (Routledge Revivals)

An Introductory Guide

David Clark

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This book, first published in 1982, addressed the need for a fresh and comprehensive guide to the rapidly expanding area of urban geography. Drawing on examples from cities in a number of countries, including the U.S.A., David Clark outlines the contribution of geographers to the understanding of the city and urban society, and analyses the growth of the urban environment alongside planning and policy. A thorough and unique study, this title will be of particular value to undergraduate students, as well as laying the foundations for a more advanced study in urban geography and planning.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Urban Geography (Routledge Revivals) an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Urban Geography (Routledge Revivals) by David Clark in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

1 | THE FIELD OF URBAN GEOGRAPHY |

The modern city is the product of an extremely long process of development. Research workers interested in early civilisations have identified a number of settlements as early as the fifth century BC to which they accord the title of city, although these places were invariably small, thinly scattered and easily reverted to village or small town status. Today, over 75 per cent of the population of the UK, USA, Canada and Australia live in centres which are termed ‘urban’ in the census, and the effects of cities are experienced daily by those who live in the remotest ‘rural’ areas. Rather than being an exceptional settlement form in a basically rural economy, the city has become the central focus of social and economic activity and influence in modern urban society.

In view of this contemporary importance, it is not surprising to find that research workers have tried to build up an adequate framework of knowledge in order to make it easier to understand and plan for the city. This task has occupied a large number of specialists drawn from a wide range of fields in the social and environmental sciences. No one discipline can claim to monopolise the study of the city since urban problems cut across many of the traditional divisions of academic inquiry. Equally, no single methodology predominates in urban analysis for the complexities of urban life necessitate the adoption of a wide variety of approaches. It is in the interdisciplinary nature of urban problems that the city poses the greatest difficulties to the analyst. Progress in urban understanding requires the fusion of insights derived from a number of disciplines each of which approach the study of the city in their own distinctive way.

Geography is the scientific study of spatial patterns. It seeks to identify and account for the location and distribution of human and physical phenomena on the earth’s surface. Emphasis in geography is placed upon the organisation and arrangement of phenomena, and upon the extent to which they vary from place to place. Although it shares a substantive interest in the same phenomena as other social and environmental sciences, the spatial perspective upon phenomena which is adopted in geography is distinctive. No other discipline has location and distribution as its major focus of study. It is the characteristics of space as a dimension, rather than the properties of phenomena which are located in space, that is of central and overriding concern.

Geography is scientific in so far as it aims to develop general rather than unique explanations of spatial patterns and distributions. It proceeds from the assumption that there is basic regularity and uniformity in the location and occurrence of phenomena and that this order can be identified and accounted for by geographical analysis. In examining spatial structure, geography focuses upon those distributional characteristics that are common to a wide range of phenomena. To this end, emphasis in geographical study is placed upon models and theories of location rather than upon descriptions of individual features. The overriding aim is to develop an understanding of the general principles which determine the location of human and physical characteristics.

Urban geography is that branch of geography that concentrates upon the location and spatial arrangement of towns and cities. It seeks to add a spatial dimension to our understanding of urban places and urban problems. Urban geographers are concerned to identify and account for the distribution of towns and cities and the spatial similarities and contrasts that exist within and between them. They are concerned with both the contemporary urban pattern and with the ways in which the distribution and internal arrangement of towns and cities have changed over time. Emphasis in urban geography is directed towards the understanding of those social, economic and environmental processes that determine the location, spatial arrangement and evolution of urban places. In this way, geographical analysis both supplements and complements the insights provided by allied disciplines in the social and environmental sciences which recognise the city as a distinctive focus of study.

Types of Urban Geographical Study

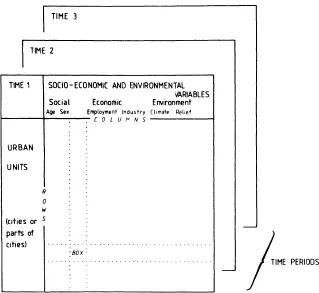

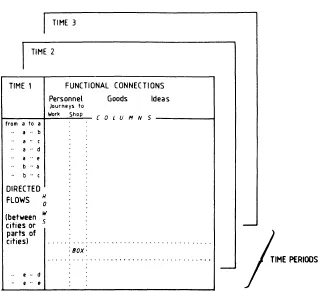

The scope and nature of urban geography is best illustrated by reference to the data on towns and cities that typically form the starting point for urban geographical study. Two basic types of data are in fact necessary to summarise the geographical characteristics of urban places, the one relating to land using activities such as population, housing and industry, the other to the different types of exchange, linkage and interaction which take place within and between centres (Figure 1.1). In the formal geographical data matrix, cities or parts of cities are listed down the rows, while variables on the contemporary demographic, economic, political and environmental characteristics of each place are entered across the columns, so that the observations or ‘geographical facts’ in each cell of the matrix record the extent to which each characteristic is present in each place. It is thus possible by reading along the rows to build up a detailed picture of the social and economic activities present in each centre or, by scanning the columns, to see how places vary in terms of the incidence of a particular variable or characteristic. An historical perspective is provided by the addition of data for previous years and this has the effect of making the formal geographical data matrix into a formal geographical data cube. As many ‘slices’ can be added to the cube as there are years for which data are available. The formal geographical data cube contains comprehensive information on the land using activities of a wide range of urban activities at a number of points in time.

Figure 1.1: Geographical Data Cubes

Formal Geographical Data Cube

Functional Geographical Data Cube

The functional geographical data matrix summarises the flows, movements and exchanges that are generated by, and in turn maintain, the land using activities. In this matrix, urban places are entered into the rows in pairs, and exchanges between places of personnel, commodities and ideas are recorded across the columns, so that the cells index directed volumes of traffic. The complexities of inter-and intraurban exchanges mean that matrices of functional geographical data tend to be very large. For example, for a simple five city system, there are 25 rows of directed movements and as many columns as are necessary to accommodate all the traffic flows. Addition of similar data for previous years transforms the matrix into a functional geographical data cube which indexes the characteristics of urban movements in both a temporal and a spatial dimension. These two cubes can be thought of as conceptual devices for organising the data which are of primary interest to urban geographers.

Working from these data cubes, it is possible to identify three primary modes of urban geographical study (Berry, 1964). The first is the ‘systematic’ approach to urban geography and involves the examination of selected columns of variables so as to see how centres differ from, or are similar to one another in terms of their land use or interactional characteristics. Studies of this type are concerned with the spatial variation of particular features and give rise to distributional maps, as, for example, the distribution of cities according to population size or importance as a traffic focus. Mapping of socio-economic characteristics or flow patterns is a basic step in geographical study and is commonly undertaken as a preliminary to more advanced forms of urban analysis. A second approach is to focus upon selected rows or parts of rows so as to compile an inventory of the socio-economic or traffic mix of individual centres. This perspective is ‘regional’ in the sense that the city is regarded as an area, and attention is focused upon the totality of socio-economic and interactional variation within it. Examples of this approach are to be found in urban atlases which map a wide range of information about the geographical characteristics of an individual city. The third type of study involves the examination of a ‘box’ consisting of a number of rows and columns of the matrix. This involves elements of both the ‘systematic’ and the ‘regional’ approach and examples are provided by studies which seek to classify urban areas on the basis of their socio-economic or interactional character.

These column, row and box approaches to the data represent the most elementary modes of urban geographical study. More advanced analysis may involve comparative studies in which attention is focused upon the degree of similarity between pairs or sets of columns and rows. For example, the extent to which employment structure relates to the size of cities would be examined by comparing and correlating selected columns of data in the matrix. Similarly, studies of comparative urban structure would focus upon pairs of, or series of rows, so as to see how the socio-economic or interactional character of one place differs from or is analogous to other places. The availability of data for previous years increases the range of approaches considerably since it means that the five types of urban study so far defined can be undertaken in a temporal context. Urban historical geography is, therefore, concerned with identifying and explaining the nature and extent of ‘systematic’, ‘regional’ and ‘comparative’ changes in urban spatial character.

As well as identifying the major types of urban geographical study, the data cubes point to the existence of a number of different levels of geographical inquiry. Data on economic and interactional character may be assembled for many different types of urban unit, including census enumeration districts or tracts, wards, urban places and urban regions, and by changing the entries in the rows, it is possible to study the city at a number of spatial scales. In conceptual terms, the range of scales is infinite and continuous, but geographers tend to focus upon processes and patterns at either the inter-urban or the intra-urban level. In inter-urban studies, towns and cities are the basic units of analysis, and emphasis is placed upon their structural similarities and differences, and the extent to which they interact and interdepend as parts of an urban system. Conversely, at the intra-urban level, the individual city is the focus of attention and analysis is directed towards the identification and explanation of internal patterns of land use and interaction. Some of the most important questions in urban geography surround the extent to which processes and patterns which are observed at one scale are present at the other, and how they are related.

The Changing Focus of Urban Geography

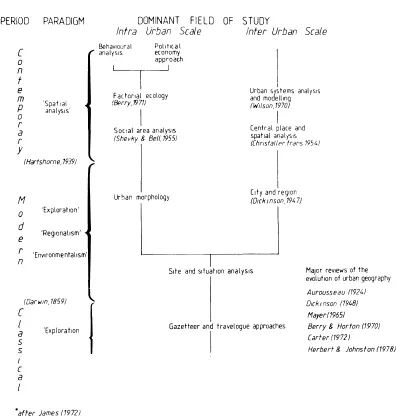

Although the concern with the spatial structure of the city has been central to urban geography since its emergence as a sub-discipline, the various types of urban study outlined above have received different emphasis at different times in the past. Urban geographers have not held a static view of their subject, rather the consensus as to what are the main issues requiring geographical investigation has changed markedly. Such shifts of emphasis are largely a product of changes in the philosophy and methodology of geography as a whole. Whereas geography in the early twentieth century was preoccupied with exploration and discovery, with the relationship between man and his environment and with defining and describing regions, primary attention since 1945 has been placed upon spatial modelling and spatial analysis (James, 1972). This emergence of spatial analysis as an accepted central focus or paradigm represented a fundamental redirection of geographical inquiry which affected all branches of the discipline in the 1950s and 1960s. Today, spatial analysis with its emphasis upon pattern is being increasingly challenged by those who would direct more attention towards the processes that give rise to geographical distributions. Urban geography as a consequence has undergone and is undergoing some major changes of focus from its early concern with the siting and situation of cities through to its present-day interest in the behavioural and political aspects of urban structure (Figure 1.2).

Urban geography has a long tail but a short body. It can claim to have origins in the writings of the ancient Greek scholars, Eratosthenes and Strabo, but its existence as a sub-discipline is very much a feature of the present century, and indeed of the last thirty years. Pre-twentieth century works were strongly descriptive and typically amounted to little more than observations on the physical appearance and subjective impressions of urban places. For example, Martyn’s geographical magazine of 1793 was concerned to describe the architectural features of English cities. Similarly, Pinkerton’s (1807) ‘modern georgraphy’, contained a brief account of the chief cities and towns in England according to their dignity, opulence, population and location. These gazetteer approaches were of some value to the traveller, but were not sufficiently systematic or penetrating in their descriptions to form the basis of a scientific urban geography.

Figure 1.2: Major Stages in the Evolution of Urban Geography

For Carter (1972) it was the replacement of description by interpretation of location which laid the foundations for modern urban geography. From the pioneering works of Hassert (1907) and Blanchard (1911), a form of urban geographical work emerged, which centred around the analysis of the site and situation of towns and cities. This approach was environmental in emphasis and assumed that general location and setting were primary determinants of urban character and that the origins and development of the town were a response to local physical conditions. Site and situation studies typically had two elements; a detailed description of different types of urban site and an analysis of the effects of location and situation upon urban growth and form. The approach is fully illustrated in Taylor’s Urban Geography (1949) which he claimed to be the first urban text in English. It consisted of a complex classification of urban sites and an analysis of over 200 towns in terms of their situation, relief and climate. For Taylor, it was logical to discuss sites of towns in an order based essentially on varying importance of local topography. His classes were, therefore: cities at hills; cuestas; mountain corridors; passes; plateaux; eroded domes; ports, including fiords, rias, river estuaries and roadsteads; rivers, falls, meanders, terraces, deltas, fans, valleys, islands; and lakes. All of these are ‘controlled primarily by the topography of their sites’ (p. 12). Those where the topography is less obvious are cities on plains, cleared out of forests and in deserts. Cities developed to serve special human needs include mining, tourist and railway cities, the first two being located in reference to special qualities in the environment. Miscellaneous types are planned, ghost, boom and suburban towns. A similar approach which stressed the importance of the physical environment was advocated as late as 1948, when Dickinson argued that the determination of site and situation was ‘the first task of the geographer in urban study’ (Dickinson, 1948, p. 12).

The physical environment undoubtedly does set general limits to urban development, but the detailed classification and analysis of site and situation proved unable to account for similarities and differences in urban character. One problem with an approach which placed so much emphasis upon the physical environment was the comparative neglect of the socio-economic features of towns as reflected in housing and industry; the other was the relative lack of attention which was given to historical factors. This imbalance was partially redressed by the emergence of a type of urban geographical study which focused on the layout and build of towns viewed as the expression of their origin, growth and function. Urban morphology studies sought to classify and differentiate towns in terms of their street plan, appearance of building and function or land use. They originated in Europe, especially in Germany, where the rich variety of settlement layouts and building types, which reflect many changes of architectural style, pose especially challenging problems of classification to the analyst. Examples of this approach include Müller’s (1931) study of Breslau which proposed a classification of houses based upon roof types, Geisler’s (1924) survey of architectural styles in Danzig and Martiny’s (1928) essay on the morphology of German towns which distinguished on functional grounds between natural urban forms and those which resulted from conscious urban planning. These early studies in urban morphology were criticised by Dickinson (1948) because the approach was empirical rather than genetic and it is ‘only the latter which permits the recognition of the significant’ (p. 21). Subsequent work by Conzen (1960, 1962) did much to counter this shortcoming by establishing a basic conceptual framework for urban morphological study, but the approach remained essentially descriptive and proved incapable of leading to general statements and explanations of urban structure and form.

Urban morphology studies were paralleled in the inter-war period by a focus at the inter-urban scale upon the city and its surrounding region. For Dickinson (1948), the urban settlement in general has a two-way relationship with its surroundings that extends beyond its political boundary. First, the countryside calls into being settlements called urban to carry out functions in its service. Secondly, the town, by the very reason of its existence, influences in varying degree its surroundings through the spread of its network of functional connections. Urban-rural links were examined incidentally as part of site and situation approaches, but with the growing realisation of their functional importance, they became a central focus of attention. At one level, city regional studies sought merely to identify urban spheres of influence by mapping indices of commuting (Chabot, 1938), food supply (Dubuc, 1938) and telephone calls (Labasse, 1955), but at another they involved comprehensive investigations of the role of functional regions in spatial organisation. This latter approach was of considerable academic and practical importance and is represented by Dickinson’s City, Region and Regionalism (1947). City regional studies established a major fiel...