eBook - ePub

International Marketing (RLE International Business)

A Strategic Approach to World Markets

Simon Majaro

This is a test

Share book

- 4 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

International Marketing (RLE International Business)

A Strategic Approach to World Markets

Simon Majaro

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Re-issuing this successful book in its seventh editionthe author starts with an overview of basic marketing concepts and their applicability on an international basis. It then covers each ingredient of the marketing mix and explores them in relation to multinational markets. Each ingredient is studied in the light of the fundamental question: 'How far can it be standardised internationally or in a research-based cluster of countries?' Research, planning and organisation problems receive particular attention. A whole chapter is devoted to 'Creativity and Innovation' on a global scale.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is International Marketing (RLE International Business) an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access International Marketing (RLE International Business) by Simon Majaro in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Marketing internazionale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Chapter 1

The Path Towards Internationalisation

Two major developments have imperceptibly become the vital forces that have determined the strategic route that modern firms have taken. They are:

The marketing concept

Internationalisation

Internationalisation

Many writers have dealt with both subjects. The literature abounds with treatises on both marketing and internationalisation. However, these subjects are normally treated as two separate disciplines. It is seldom appreciated that marketing and internationalisation are not only related but interdependent. Many firms have accelerated the development of the international dimension to their activities through the stimulus of the international marketing vistas they had perceived. General Motors, Nestle and IBM have become international companies in the main because at a certain stage in their respective development they identified promising opportunities in world markets. Having established that the domestic market offered limited scope for expansion in terms of growth and profits, these firms sought to exploit opportunities abroad and that meant marketing opportunities. This is probably the main reason why firms based in small countries like the Netherlands and Switzerland embarked on the road to internationalisation at an earlier date than their American counterparts.

Whilst firms claim to have initiated the internationalisation process for a host of reasons, it is not always recognised that probably the most convincing rationale is the desire to harness global marketing opportunities. A firm that is enjoying continuous growth and profitability in its domestic market is far less prone to the internationalising process than the firm that has encountered tough competition at home with eroding margins. In other words, ‘internationalisation’ is a corporate strategy with strong marketing ‘inputs’ rather than an inevitable evolution. A firm can be very successful and remain so without indulging in foreign adventures. On the other hand, with the ever-shortening product life cycle tendency, a firm may find that shunning international markets may in certain circumstances spell stagnation and vulnerability. The message implied in what has been said so far is that the internationalisation process can provide a firm with rich new pastures for planned growth and prosperity but it must be based on clearly thought out and quantified marketing justification. Without such information, the road to internationalisation can be a rocky one.

Too many writers seem to imply that the world enterprise is an end in itself. In his paper ‘The Tortuous Evolution of the Multinational Corporation’, Howard V. Perlmutter concludes:

‘The geocentric enterprise offers an institutional and supranational framework which could conceivably make war less likely, on the assumption that bombing customers, suppliers and employees, is in nobody's interest. . . .’*

This sounds extremely idealistic. Ford Motor Company is operating in the UK and in many other parts of the world mainly because the marketing objectives of the firm are well served by this mode of operation. When Henry Ford II announced in public during a serious industrial dispute that he had no intention of authorising further investments in the UK he forgot why his firm had come to Britain in the first place. Ford came to Britain because it probably made good marketing sense to do so. Ford internationalised its operations because of an underlying marketing stimulus. If, for marketing reasons, the UK ceases to offer attractive opportunities, at that point Ford may cease to invest in that country. Of course there are other elements in such a decision: labour availability, logistics, infrastructure, location convenience, etc. However, in reality the marketing justification is the most powerful. As long as the UK remains a large and promising market for automobiles, marketing considerations will overrule Henry Ford's personal emotions regardless of the pain that industrial relations may inflict upon the firm's management. On the other hand, in the event that marketing opportunities melt away, Ford will probably refrain from sinking more funds in the UK however docile the British workers and the unions become. So much for a large multinational's idealism.

The hypothesis that emerges, therefore, is that the internationalisation of a firm is to a great extent the corollary to its marketing aspirations and needs. A firm becomes an international enterprise not because it desires to become one, but because it is forced to seek wider markets outside its domestic scene. Internationalisation is a corporate strategy, just like mergers, acquisitions and diversification. Marketing is the underlying justification for such a strategy. Unfortunately, the interdependence between marketing and internationalisation is often overlooked by management and decisions to internationalise are taken with inadequate marketing justification. This is probably why so many firms encounter severe difficulties in achieving success in their international operations. The domestic company that decides to seek its fortunes in world markets is well advised to approach its strategy with caution and systematic planning. The number of pitfalls is enormous; at the same time, the rewards for the manager who enters world markets with a full awareness of the tasks to be undertaken, coupled with a deep-rooted sensitivity towards the international consumer, can be very substantial.

* Howard V. Perlmutter, ‘The Tortuous Evolution of the Multinational Corporation’ Columbia Journal of World Business, vol. IV, 1969.

Chapter 2

The Organisation of the International Firm—A Conceptual Framework

The so-called ‘multinational’ firm is frequently in the news nowadays. Anxieties over the growth and power of the multinational companies show no sign of fading away. The US Government has been seeking to establish how far such firms have been a contributing factor to the dollar decline. In Brussels EEC Commission officials have been discussing proposals for control procedures over multinationals including changes in tax treatment. In the UK Roche came into conflict with the Government on the question of pricing and profits of two drugs supplied to the National Health Service.

Many examples can be added to illustrate how the multinational firm has ceased to enjoy the kind of immunity that its international omnipresence had bestowed upon it previously. It is difficult to assess at the present moment how far this movement is likely to go and what are the longer term implications of this kind of agitation. The significant point to remember is that many firms operating internationally are contributing substantially, directly or indirectly, to the welfare of the communities in which they operate. A study conducted by the Conference Board in the USA covered the activities of 218 US companies which have foreign operations and listed the kind of aid that the companies in question contributed to local activities. Among the forms of aid were cash grants to technical schools and universities, part-time or vacation employment for students, exchange programmes for travel, study or work overseas, emergency relief operations and grants to hospitals and clinics.

In other words not all multinationals are as ‘wicked’ as the recent spate of adverse publicity seems to imply.

The realisation that mounting social, economic and moral pressures are also undergoing an internationalisation process must be recognised by companies wishing to operate on a multinational scale. Indeed it is difficult to see how any company operating on an international basis can hope to survive without paying full heed to the wind of change that is sweeping world markets.

The adjective ‘multinational’ will be avoided in this book. It evokes too much controversy among both academics and international businessmen. There are those who distinguish between an ‘international’ firm and a ‘multinational’ firm. The former, according to a number of writers is ‘bad’, the latter is ‘good’. A most artificial and unsatisfactory classification. Others go as far as to claim that a domestic firm, say a British company with considerable overseas interests, is neither a multinational nor an international firm—it is, according to them, purely a domestic company which happens to have foreign interests! Thus Lord Kearton, when he was the Chairman of Courtaulds, insisted that his company was not multinational in so far as three-quarters of its sales emanated from the UK facilities. ‘Investment in Britain is our first priority’, he said, ‘and investment overseas is complementary to this’.... We see once again the trap of semantics. Does it really matter what title one ascribes to a firm? Is Courtaulds in any way exonerated from the rigours of social responsiveness to the needs of the communities it serves just because the stigma of ‘multinationalism’ has been removed from it by its former Chairman's eloquence?

At the other extreme, one also meets the notion that a company that has foreign subsidiaries—with or without manufacturing facilities is automatically classified as an international firm.

Surely what one decides to call a company with international interests is immaterial. What is important is that a firm that has embarked on an internationalisation path rapidly develops the awareness of the need to consider and meet the expectations of the various communities in which it proposes to operate. This is the most fundamental principle of a successful international marketing effort.

At this point it may be appropriate to attempt to categorise the kind of organisational patterns that exist among companies operating internationally. The reader will note that the terminology multinational firms, international firms or even transnational firms is avoided. We are talking about firms with international operations or interests; whether these are companies with many manufacturing and distribution centres abroad or firms that have just embarked on the internationalisation path is quite immaterial. The conceptual framework described should apply to most situations and it is useful for a firm's management to try to understand the kind of ‘culture’ that the company has developed or is likely to develop in the future. A firm that has selected, knowingly or by accident, a certain organisational style must be aware of the implications both for the short-term and the longer-term development of its international effort. As we shall see later, a style which is inherently efficient in the use of men and resources may also contain elements of weakness in terms of sensitivity and responsiveness to markets and their special needs. No pattern is perfect, nor is it intended to suggest that one kind of structure is better than another. The options to be described are purely a conceptual classification based on an empirical observation of a large number of firms operating on the international scene. The acceptance of this framework is helpful in so far as it will provide a basis for subsequent discussions pertaining to the international marketing function. It must be emphasised that no recommendations are being made here as to correct solutions, nor is it being suggested that hybrid structures do not exist.

Background Concepts

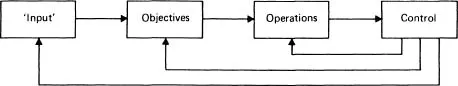

The management of any activity normally calls for the following steps:

Information gathering (‘input’)

Objectives setting

Operations

Control procedures

The control procedures in turn constitute an ‘input’ for the next cycle.

The process, in this very simplified form, can be described diagrammatically as in Figure 1.

Fig. 1 The management of activities—a simple model

The concept applies not only to the management of business problems and activities, it applies to many decision areas in day-to-day life. This is how we manage the purchase of a car. This is how we select a holiday. This is how we choose a new job. Without information the choice of objectives may be ill-conceived and without objectives operations may be totally irrelevant. Finally, if we do not control what we have done, we cannot judge whether or not we have been successful in what we have set out to achieve. Furthermore, without control procedures we may repeat the same mistakes when we come to plan the next cycle.

In a firm we have an intricate conglomeration of decision levels. Whilst each level has a different task to perform it is important that everybody in the organisation functions in an integrated way. Once again to simplify the description we can divide the firm into three distinct levels:*

Strategic

Management

Operational

Briefly, the strategic level has to identify the expectations of the stakeholders (e.g. shareholders, employees, the community, the bankers, the unions, the government etc.); determine the firm's objectives (the attainment of which will meet the stakeholders’ expectations); decide on the type of resources that will be required if the firm is to attain its objectives and select the most appropriate corporate strategy for the firm to adopt.

The management level has the task of translating corporate objectives into functional and/or unit objectives and ensuring that resources placed at its disposal are used effectively in the pursuit of those activities which will make the achievement of the firm's goals possible.

The operational level is responsible for the effective performance of those tasks which underly the achievement of unit/functional objectives. The attainment of the latter will of course be the instrument through which the corporation as a whole can expect to achieve its overall objectives. Thus all three levels are interrelated to such an extent that failure at any level may affect adversely the firm's performance. Having an effective operational level is not enough; similarly having the brightest board of directors (assuming that in most instances the board represents the strategic level) does not guarantee success if the other levels are ineffectual.

Translating what was said about the three levels of a firm into the ‘managerial model’ shown earlier we can describe the firm's hierarchy as a pyramid. Functional activities transcend all levels. Thus, for example, the marketing function requires strategic planning as well as management activities, and finally the process is completed by the operational level undertaking the detailed tasks allotted to it such as selling, advertising, administering the warehousing procedures and so on. Each function and each level requires information, ‘input’, to be able to plan its activities and at the end of the day control procedures are also needed to measure the effectiveness of the performance. The ‘input’ and control are shown outside the pyramid They do not represent resource management activities in so far as their real role is to provide information which facilitates the managerial process...