eBook - ePub

Socio-Legal Approaches to International Economic Law

Text, Context, Subtext

Amanda Perry-Kessaris, Amanda Perry-Kessaris

This is a test

Share book

- 314 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Socio-Legal Approaches to International Economic Law

Text, Context, Subtext

Amanda Perry-Kessaris, Amanda Perry-Kessaris

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

This collection explores the analytical, empirical and normative components that distinguish socio-legal approaches to international economic law both from each other, and from other approaches. It pays particular attention to the substantive focus (what) of socio-legal approaches, noting that they go beyond the text to consider context and, often, subtext. In the process of identifying the 'what' and the 'how' (analytical and empirical tools) of their own socio-legal approaches, contributors to this collection reveal why they or anyone else ought to bother--the many reasons 'why' it is important, for theory and for practice, to take a social legal approach to international economic law.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Socio-Legal Approaches to International Economic Law an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Socio-Legal Approaches to International Economic Law by Amanda Perry-Kessaris, Amanda Perry-Kessaris in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & International Trade Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Part I

Approaching international

economic law

Chapter 1

What does it mean to take a socio-legal approach to international economic law?

Introduction

Sure, it's a subject, and sure, it exists, but if it lacks theoretical and methodological underpinnings, it is not a discipline of inquiry.

(Trachtman 2008: 45)

International economic law is not a discipline. It is a field of study. So it falls to each of us individually to decide how to approach it. International economic activities and their laws have positive, negative, variable and unknown implications at every level of social life – on our actions and interactions; on the regimes by which we govern and are governed; and on the rationalities that guide us (Frerichs 2011b: 68; Perry-Kessaris 2011a). It is possible to identify a number of ‘approaches’ to the field, each with its own distinctive analytical, normative and empirical tendencies (Twining 2000; Perry-Kessaris 2011a). There are, for example, doctrinal approaches which describe what adjudicators and legislators have written, and the public choice approaches which seek to uncover the ‘desires’ that law ‘masks’ (Trachtman 2008: 45–9; see also Shaffer 2008). But there exists no ‘general theory of international economic law’ (Charnovitz 2011: 3) by which to navigate.

Nor is it clear that any such grand narrative is needed. As sociologist Raymond Boudon has observed, theories are least useful to social inquiry when they attempt the ‘hopeless and quixotic’ tasks of identifying the ‘overarching independent variable that would operate in all social processes’, or ‘essential feature of the social structure’, or even ‘two, three, or four couples of concepts (e.g. Gesellschaft/Gemeinschaft) that would be sufficient to analyze all social phenomena.’ Theories only become useful when they ‘organize a set of hypotheses and relate them to selected observations . . . which would otherwise appear segregated’ (Boudon 1991: 519 and 520). Similarly, Joel Trachtman has argued that international economic law (IEL), like law generally, too often sets out ‘to cover ground that has already been covered’, and that such inefficiencies might be avoided if we focused some of our energies on acquiring ‘[g]reater understanding of, and agreement on, research methodology’. We might then ‘form a consensus that certain issues are already known’ and then turn to consider ‘unknown issues’ (2008: 43). What IEL really needs, then, are some of sociologist Robert K. Merton's (1957) ‘theories’ of the ‘middle range’ to enable us to consolidate, identify transferable lessons (analytical, empirical and normative), and then move more wisely onwards and upwards.

Among the array of currently discernable approaches to international economic law, the socio-legal appear to stand out as especially well placed to do the heavy lifting required of a middle-range approach, as well as the next, ‘onwards and upwards’, agenda-setting stage. The purpose of this chapter, and of the collection that it introduces, is to highlight some distinctive virtues and vices of these socio-legal approaches. Although some are reluctant to define ‘socio-legal’ work very precisely, beyond emphasising that it is interdisciplinary and sociologically attuned,2 new comers are (and perhaps old timers ought to be) keen for some clarity.3 This collection honours that tension by stopping short of a rigid definition of ‘socio-legal’ approaches. Instead it identifies three dimensions on which all ‘approaches’ to law vary (analytical, empirical, normative) and locates socio-legal approaches to international economic law along them.

Approaching law

Disciplinary boundaries should be viewed pragmatically; indeed, with healthy suspicion. They should not be prisons of understanding.

(Cotterrell 1998: 177)

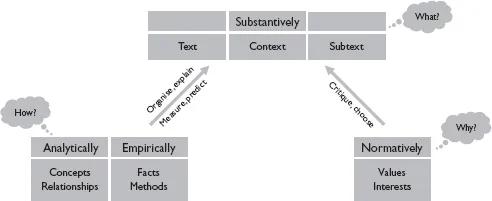

Any approach to law has normative, analytical and empirical components that determine what is approached, as well as how and why it is approached (Figure 1.1). The ‘analytical’ components of an approach are the concepts and relationships it deploys to organise the field of study. The ‘empirical’ components of an approach are the facts and methods that may be used to confirm the real-life existence, or absence, of concepts and relationships. The normative components of an approach are the values and interests that it foregrounds or privileges.

For example, a ‘legal’ approach is an in-discipline approach. It involves the ‘rationalisation of and speculation on the rules, principles, concepts and legal values considered to be explicitly or implicitly present in legal doctrine’; and it ‘constitutes a major focus of past and present legal philosophy’ (Cotterrell 1992: 3, my emphasis).4 In other words, its substantive focus (what), analytical and empirical tools (how), and normative underpinnings (why) are all strictly legal. For those who adopt a black letter, positivist, strictly ‘legal’ approach, law comes first and is the substantive focus. There is no need to look any further.

Figure 1.1 Approaching law.

Law has been travelling on (or returning to: see Frerichs, this volume) an interdisciplinary path for some time now. In fact, Gunther Teubner argues, ‘we are faced with legal pluralism’ not just in the sense of ‘a plurality of local laws, of ethnic and religious rule-systems or of institutions and organisations’, but also in the ‘more radical sense’ of a ‘plurality of incompatible rationalities, all with a claim to universality in modern legal scholarship’ (1997a: 157). Law has long been caught in a ‘collision of discourses’ – a post-modern ‘polytheism’ in which ‘many Gods have even taken residence in the inner sanctum of law, in legal theory and jurisprudence’ no less, as well as the bustling corridors of legal practice (Teubner 1997a: 149, original emphasis). Notable interlopers have been ‘political theories of law’ such as legal realism, the law and society movement, critical legal studies, feminist jurisprudence and critical race theories; and the more radical, even destructive, economic theories of law (Teubner 1997a: 152).

Law is not unusual in this respect. According to Klein, epistemologists are generally agreed that ‘heterogeneity, hybridity, complexity and interdisciplinarity [have] become characterizing traits of knowledge’ (Klein 1996: 4). Such ‘boundary work’ routinely crosses the ‘demarcations’ between disciplines, sub-disciplines, hybrid fields and ‘clusters’ of disciplines; between ‘taxonomic categories’ such as knowledge and research that are ‘hard’ and/or ‘soft’, ‘basic’ and/or ‘applied’, ‘quantitative’ and/or ‘qualitative’, ‘objective’ and/or ‘subjective’; between ‘sectors of society’ such as ‘industry, academe, government and the public’ (Klein 1996: 4–5). For example, sociology has made inroads into (or back to) the substantive heartland of other disciplines. Examples are Economic Sociology5 and its less developed cousin, Economic Sociology of Law. In the latter case, sociological approaches (empirical, normative, and analytical) are used to investigate relationships between law and economy (see Cotterrell, Frerichs, Gammage and Halliday and Block-Lieb in this volume; Ashiagbor et al. forthcoming 2013).

Furthermore, it is by now accepted from the radical fringes to the staid centre that we must reach beyond the discipline of law to economics, political science, cultural history, anthropology and geography if we are to understand international economic law (Jackson 1995: 599). In the mainstream Journal of International Economic Law and American Journal of International Law we find articles drawing on the analytical and empirical tools of history (Lowenfeld 2010), economics (Sykes 1998; Trachtman 2002), politics (Pauwelyn 2008) and political economy (Howse 2002; Slaughter et al. 1998 and Vandevelde 1998) to aid our understanding of international economic law. As Aurora Voiculescu puts it in this volume, ‘the imagining of the new normative survival kit for the neoliberal programme, including IEL, necessitates a re-engagement with disciplines such as anthropology, sociology, moral philosophy and, of course, politics.’

So it is unsurprising that self-describing socio-legal scholars in the US and the UK have for some years been independently concerned with issues of relevance to international economic law, and have recently begun to move into the field in organised fashion.6 The remainder of this chapter explores in greater detail how a ‘socio-legal’ approach distinguishes itself among other interdisciplinary approaches to international economic law. First, what is approached? Socio-legal approaches consider not only legal texts, but also the contexts in which they are formed, destroyed, used, abused, avoided and so on; and sometimes their subtexts. Second, how is socio-legal thinking and practice undertaken? It is interdisciplinary, drawing (analytically) on the concepts and relationships and (empirically) on the facts and methods of the social sciences, and sometimes the humanities. Third, why is socio-legal thinking and practice undertaken? Socio-legal approaches to international economic law aim to understand legal texts, contexts and subtexts, sometimes for the objective purpose of achieving clarity, sometimes with a view to changing them.

What is approached?

Socio-legal approaches consider not only legal texts, but also the contexts in which they are created, destroyed, used, abused, avoided and so on; and sometimes their subtexts. This substantive ‘what’ of socio-legal approaches is captured in the subtitle to this volume: text, context, subtext (Figure 1.1). I cannibalise this tripartite riff from the elegant phraseology of Sabine Frerichs:

By text I mean the legal text, that is, the written rules and doctrines, or what can be considered black letter law. By subtext I refer to the moral subtext of a legal text, that is, its implied or deeper meaning. This includes the different notions of justice underlying a legal argument which make it necessary also to read between the lines. By context I refer to the social context of a legal text, that is, its forceful link with reality. In this perspective, law is not a self-contained discourse but a powerful social institution.

(Frerichs 2012: 9, my emphasis)

Text

The most broadly recognised ‘texts’ of international economic law relate to international trade, and can be traced back to the negotiation of reciprocal trading agreements in the fifteenth century, through the development of the world trading system in the late 1940s, and forward through the negotiating agenda of the World Trade Organization (Charnovitz 2011: 6). But most would now agree that international economic law is much more than that.

It is ‘economic’ in the sense that it addresses the activities of production, distribution, exchange and consumption. It is ‘international’ in the classic understanding of international law is as of law among nations (inter nations), but also in the broader sense of being global. That is, the legal and/or the economic phenomena in question exist beyond national boundaries – whether regional, international, transnational and/or multinational. And, in keeping with broader ‘glocalisational’ trends, the field requires a consideration of local laws and economies. Indeed, ‘perhaps the label “international” survives because of lawyers’ attachment to traditional labels’ (Valentina Vadi, personal communication 2012).

Many have tended towards a pragmatic and functional approach to defining the text of IEL, honouring the spirit of Roger Cotterrell's advice not to allow fields of study to become ‘prisons of understanding’ (Cotterrell 1998: 177). Their interest has been to ‘correlate’ laws with those actions and interactions ‘which they purport to regulate or from which they spring’. They have felt free to identify and ‘fructify’ the laws and institutions of other ‘specialized fields of public international law’ – those directed primarily towards regulating ancillary fields such as ‘culture, development, environment, public health, human rights, intellectual property, labor rights, monetary and currency issues, the sea, and telecom’, without ‘necessarily classifying . . . as part of ’ international economic law (Charnovitz 2011: 4, my emphasis). The result is a field that is extensive yet not overwhelming, malleable but not shapeless.

The ‘text’ under consideration ‘may take the form of hard law or soft, of conventions and best practices, of model laws or legislative guides, of prescriptive or diagnostic standards’ (Halliday and Block Lieb this volume). In cases where the law in question is international in origin, it ‘cannot be separated or compartmentalised’ from general international law. Despite clearly identifiable trends towards fragmentation in the international law (Koskenniemi 2011: 265; Flores Elizondo, Schneiderman and Yearwood in this volume), the interpretation and development of international economic law continues to affect, and be affected by, interpretations and developments in general international law (Jackson 1995: 599). International economic law is often distinguished from ‘private’ international commercial law governing particular transactions such as contracts (Charnovitz 2011: 7). But public and private actors and activities are in constant interaction, so it does not do to be too rigid on the matter (see Halliday and Carruthers 2009). Indeed, in this volume Roger Cotterrell specifically seeks to ‘shift focus . . . away from the idea of law as rooted in the governmental activity, agreements or relations of nation states’ and ‘towards a recognition that law is also rooted in the projects and aspirations of actors operating in networks of community’, but at the same time to ‘suggest that these contrasting perspectives are interdependent’ (see also Xu in this volume).

Terrence Halliday and Susan Block-Lieb (in this volume) encourage us to pause a moment, to smell the ink, to ‘confront[ ] who crafts the text, what form it takes, and how it is carried into global and national arenas of economic activity.’ For the text is the result of decisive ‘recursive’ social processes that have all too often been ‘left by sociolegal scholars to political scientists or jurists’ (Halliday and Block-Lieb). Deval Desai answers the call with an examination of how ‘the “text” of agreements between mining corporations and indigenous communities’ is ‘framed’ through ‘discourses of law, actors and the indigenous rights professional’ (Desai in this volume). Likewise, Ioannis Glinavos charts the failed ‘struggle towards text’ to regulate the bonus culture in the banking industry (Glinavos in this volume).

Context

Whether or not they pay much attention to the text, those who take a socio-legal approach always set out to explore the actors, actions and interactions that form its context. This requires more than a legal analysis – more, for example, than simply tracking the, undoubtedly thrilling, evolution-by-interpretation of the US Alien Tort Statute from a 30-odd word side issue in 1789 to one of the greatest sources of hope for securing corporate liability for human rights abuses in the US Supreme Court case of Kiobel v. Royal Dutch Petroleum, Co. (Shell) on-going in 2012.7 It requires an exploration of law's ‘link with reality’ (Frerichs 2012: 91).

It may not always be immediately obvious, but international economic actors (producers, distributors, exchangers, consumers, regulators, debtors – even, Actor Network Theorists would argue, objects: Cloatre 2008) both state and non-state (see Scheiderman and Shields, both this volume), their actions and their interactions, are always embedded in wider social life. Indeed, all actors are always engaged, to different degrees (from fleeting to stable), in multiple types (in the terms of Max Weber: traditional, instrumental, belief-based and affective) of social action, of which economic action and interaction are just one (instrumental) sub-type. For example, foreign direct investment creates and alters relations between many types of human actor – buyers and sellers, employers and employees, suppliers and retailers, consumers and producers, shareholders and company officials, regulators and regulatees – who may be located in the home states from which investments originate, the host states in which investments are made, and beyond. And these actors will at the same time be engaged in multiple, entangled, other forms and types of interactions. So, by applying Roger Cotterrell's socio-legal ‘lens of community’ to foreign investor–government–civil society relations in Bengaluru (Bangalore), I have been able to expose how the Indian ‘legal system succeeds, and fails’ to support actions and interactions of a ‘broad range of actors, each with different motivations . . . but all requiring the support of the same facilitator for their productive interaction: mutual interpersonal trust’ (Perry-Kessaris 2008). Likewise, in this volume, Roger Cotterrell and Ting Xu apply the lens of community to explore law in the contexts of internet developers and Chinese lineage-based communities respectively.

We may sometimes forget that ‘economic’ actions and interactions are part and parcel of wider ‘social’ life. In particular, our understandings of economy might sometimes become disembedded from wider social life, in the sense that the analytical and normative approaches (or rationalities) that are central to economic actions and interactions may be confused with, and privileged over, those that are central to non-economic actions and interactions. Sometimes that disembedding can even have a performative effect – we begin to ‘think economics, do economics and feel economic’ (Perr...