eBook - ePub

Camp Life and Sport in Dalmatia and the Herzegovina

Anonymous Snaffle

This is a test

Share book

- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Camp Life and Sport in Dalmatia and the Herzegovina

Anonymous Snaffle

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First Published in 2005. This largely unknown travel book, written by a sporting and hunting enthusiast in 1896, recalls his journey with his wife and two dachshunds in what was then a largely unknown part of Europe. Not even Thomas Cook had conducted tours east of Trieste and our two travellers were exploring territory which was actually less well known to the Victorian traveller at the time than Egypt or Brazil. The author was an English gentleman, keen sportsman and traveller.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Camp Life and Sport in Dalmatia and the Herzegovina an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Camp Life and Sport in Dalmatia and the Herzegovina by Anonymous Snaffle in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

IN THE LAND OF THE BORA.

PART I.—DALMATIA, 1894.

CHAPTER I.

I CAN hardly say what first turned our thoughts towards the eastern shores of the Adriatic, but of this I am sure, that two years elapsed from the time that the word “Dalmatia” was first mentioned between us, until that at which our plan took a concrete form. The next allusion either of us made to the province—I beg its pardon, the kingdom—was when I discovered in a German sporting paper, Der Weidmann, that the shooting there was entirely free. This naturally strengthened my inclination towards it, even in spite of the fact that the editor of the above-named periodical, writing privately, said that the sport was very indifferent. Unfortunately for himself, he went on to give his reason for saying so, which was that it was free. Now, I have in the past enjoyed, and hope in the future to enjoy again, many good days’ shooting in lands where game laws are not—not that, by the way, this is the case in Dalmatia. Moreover, he went on to speak in flowing terms of the sport attainable in Bosnia and the Herzegovina, and I could not believe that none of the bears, wolves, and other beasts, which he spoke of as existent there, ever crossed the frontier.*Another authority, also German, said there were plenty of waterfowl, and also stonehens (Steinhühner). What these were I could not guess, unless ptarmigan (Schneehühner) were meant. This same writer said the jackal was to be found on some of the islands ; but although he is doubtless a rare beast in Western Europe, I could hardly fancy myself treating my old friend the jack as food for “villanous saltpetre” after the many pleasant gallops he had provided in bygone years. I was surprised, though, to find that neither of them mentioned the boar as an inhabitant of the district, knowing what good bags of these animals the Corfu garrison, in the days when it was an English possession, used to make on the Albanian coast.

After all, sport was really a secondary consideration, as it often must be when ladies form part of an expedition.

All the authorities seemed to agree in this, that Dalmatia offered a delightful climate, lovely scenery, and, above all, something new. This really was the great attraction. When your neighbour at every dinner-party is equally familiar with Cairo and Calcutta, Boston and Bendigo, Reykjavik and Rio, it is really an achievement to discover a country with which the British tourist has not yet familiarized himself. That this is the case with Dalmatia, I think I can easily prove. When I first thought of going there, I wrote to ask the great—the only—Cook the fare to Spalatro. I need hardly say that he promptly furnished the required information, but he also added that he himself could not personally book us beyond Trieste. This settled it. A country to which Cook had never “personally conducted” the pavid spinster or the plethoric publican was indeed a terra incognita. To be sure, our authority went on to say that there were no hotels except in the principal towns (and he might have added that they were uncommonly indifferent even there), but this to us was only holding out an extra inducement. Had we not slept peacefully many a night under canvas in the Far East, lulled to sweet repose by the long-drawn snore of the faithful chokedar.* Tents and camp gear presented no difficulty. Then we were told that to some of the islands there were no steamers, whilst to others they only ran at long and fitful intervals. Tant mieux ; so much less chance of the stray tourist having demoralized the inhabitants. Islands are naturally the homes of fishermen, who must have boats ; and these boats should convey us, camp and all, wheresoever we would wander.

After we had thus made up our minds that Dalmatia lay so far away from all we held familiar, it was rather a blow to me to find out, as I did, that I had a second cousin living there. But then he is a Jesuit, and the man who wants to visit countries where they are not to be found must go in a balloon. As he was there we determined to utilize him, and see if he could get us a servant equal to our modest requirements. He answered our letters most kindly, especially considering that he had never seen, nor perhaps ever heard of, us. He tried his utmost to dissuade us from our projected trip, pointing out the possible dangers to our health of camp-life in bad weather, quoting that well-known Adriatic bogey, the bora wind, which he felt sure would blow our tents to kingdom come ; and finally advised us to come direct to him at Spalatro, whence he would dispatch us by steamboat to the various points of interest on the coast and in the islands.

Now, I was well aware that the bora constituted a real inconvenience, and even danger, on the Dalmatian coast, but not, I felt sure, one that could not be counteracted by prudence, firstly, in choosing sheltered positions for the camps, and secondly, by only moving on those days when the natives felt reasonably secure that no atmospheric disturbance was imminent—a course which the facts of our temporary home being close to the point of departure, and of our voyages being short, rendered easy of adoption.

So we returned answer, despising the seductions of Spalatro hotels and steamboats, but promising the worthy father a visit later.

Having failed to get a servant through this medium, and also from a Zara hotel-keeper to whom we wrote—and who never answered—we were rather at a loss till my wife came to the rescue with a brilliant suggestion, Why take a servant at all? So finally, after some discussion, it was settled that we should go on the American plan, and trust to luck for any assistance in work that our own hands could not enable us to complete.

Our “expedition” was thus finally made up of my wife and self, with our two dachshunds, Waldmann and Rex—“the red dog” with whom some of my readers may have already made acquaintance in the pages of “Gun, Rifle, and Hound.” Excepting in so far that the little fellows are my inseparable companions, and proved useful watch-dogs, I must frankly admit that they were not that success in Dalmatia which they had previously been in German woods and Ardennes forests. They seemed to feel the disadvantage they were at among the rocks and mountains, and only worked really well in the vineyards and marshes. To any one who may think of following in our footsteps, I would recommend the taking of one or two pointers or setters, or preferably one of each, as the former will suffer in the feet from the sharp rocks, whilst the want of water will often knock up the latter.

Assuming that the average reader knows no more about the matter than I did before I went there, I may, perhaps, be allowed to say a little about Dalmatia. The only connection the name formerly had in my mind was that it was the native home of those quaint-looking black-and-white pointers, vulgarly known as “plum-pudding dogs,” one of which, in my young days, invariably formed part of a well-turned-out London equipage, but which now seem in a fair way to become as extinct as the dodo. In this case it will certainly not be to Dalmatia that fanciers will be able to resort to renew their stock, for I never saw a single specimen of the breed there, and can only suppose that some wag named the breed on the Incus a non lucendo principle.

These are a few facts, some of which I learnt previously to going there by studying the authorities (all foreign) on the subject, and others of which I obtained locally. Dalmatia is now, and has been since the termination of the Napoleonic wars, an Austrian province, and, by virtue of its possession, the Emperor of Austria adds to his many titles that of King of Dalmatia. It comprises the former trans-Adriatic possessions of the Venetian Republic, as well as of that of Ragusa and other lesser ones, together with a bit of Turkey handed over to Austria in 1882 (the Spizza district). In position it extends along the east coast of the Adriatic, and is, though only a narrow strip, of the respectable length of two hundred and twenty English miles. The islands, whose area bears a very considerable proportion to that of the mainland, may be roughly divided into two groups—the Northern or Liburnian Archipelago, ending near Sebenico ; and the Southern one, extending from Trau to Ragusa. Their number is enormous, but many are mere uninhabited rocks. The three largest in order of size are Lesina, Curzola, and Brazza. No better idea of the nature of the country can be given than that which can be obtained from the following statement : eleven-thirteenths of the whole country is entirely sterile, being nearly all rock.

Although Dalmatia has formed an integral part of the Austrian Empire for the best part of a century, it is only in the last fourteen years that it has become of any political importance. When, after the events of 1880, the Turkish provinces of Bosnia and Herzegovina were handed over to the safeguard of the Austrian Empire, it at once became obvious that the most convenient mode of access thereto was to be obtained through Dalmatia. On the principle of one good turn deserving another, it was the possession of Herzegovina which enabled Austria to finally subdue and to subject to her conscription the turbulent peasantry of the Crivoscie district, who, in 1869, had successfully opposed the Viennese authorities, being principally enabled to do so by the vicinity of the Turkish frontier. Most of them have since emigrated to Montenegro. It is through Bosnia alone that the Dalmatians can reach their capital by rail, from Metcović, though the route is a somewhat circuitous one, and it would be more to the point if the other line were continued from Knin ; but to this subject I shall return later. At any rate, the Dalmatian route is far the most convenient one an Englishman who wishes to visit the “administered provinces” can take.

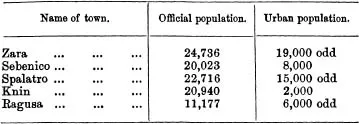

The only towns of any importance in the province are Zara, its chief town, Sebenico, and Spalatro. Of the others, none have an “official population” of ten thousand, except Ragusa. These official figures are decidedly misleading, as they refer to the electoral communes, and lead one to expect a much bigger place than one actually sees. For instance, the Commune of Sebenico extends from Vodiće to Rogosnića, say twenty-three miles. The following table will show the difference between the official numbers and the approximate population of the towns themselves:—

From which it appears that the real population of Zara only in any way approaches the published figures, whilst Knin has not a tenth of the number with which a stranger would credit it.

* Ultimately, as will appear hereafter, we had to give up all hopes of the visit to the Dinaric Alps, which formed part of our original programme.

* Watchman

CHAPTER II.

DALMATIA can be conveniently reached from England by various routes. The quickest, which was also the one we adopted, is that by the Saint Gothard, Milan, and Ancona, from which last place there is a regular weekly service of steamers to Zara. This route can, of course, be varied in a number of ways, e.g. by taking the Paris and Mont Cenis line to Milan. The cheapest route is that by Harwich, Antwerp, Luxemburg, Basle, and Innsbrück to Trieste or Pola. In this case the railway journey is also about forty-eight hours, but the sea-voyages at both ends are considerably longer. In the latter case the steamers call at several ports en route, unless one takes what the Lloyd people call their “Dalmatian” line. These boats only call at one place, Pola, between Trieste and Zara. If, however, time is no object, the others will be preferred, as enabling one to see a little of Istria, which is not uninteresting. In both the above cases I assume a start to be made from Zara, which, with the exception of some islands, is the extreme northerly point of the province.

There is, however, a third way of going out, and one to my mind infinitely preferable to either of the above, when neither time nor money is an object. This is to take the weekly Peninsular and Oriental steamers to Brindisi, and thus dispense with the tiresome railway journey, with its four or five custom-house formalities. Brindisi is in regular steamer communication with Corfu—in itself well worth a visit—and thence the steamers, touching at one or two Albanian ports, land the traveller at Cattaro, to all intents and purposes the most southerly point of Dalmatia. Another great advantage of this route is that one can take all one’s camp equipment with one, whereas, if one goes by land, it must be shipped on to Ancona or Trieste a month in advance. This southern approach is especially suitable to those who go to Dalmatia early in the year, enabling them, as it does, to go north as the season gets hotter. It is almost superfluous to add that Dalmatia is not a suitable climate for camp-life before March, even in the south. As an alternative, the Indian mail route can be taken to Brindisi by those who wish to go in spring. This port is also in regular steamer communication with Ragusa, but there does not seem to be any object in beginning in the middle of the country in this way.

I have said that we selected the quickest route. Indeed, we were obliged to do so, as our start had been delayed two months. I had intended to leave early in June, and this I still think the best time for the purpose. But August was a week old before ever we saw Dalmatia. Passing over in silence the well-known continental transit, I will proceed at once to the last stage of our railway journey. The Ancona express leaves Milan at half-past one in the afternoon, and when we had seen the last of the familiar dining-room at Bologna, the novelty of the journey commenced for us. Unfortunately, it was dark when we reached the Adriatic at Rimini, and the only evidence of its presence that night was the murmur of the surf—a sound, I think, that is always homelike to the Briton.

At Ancona we found all our camp gear except one very important item, the camp-beds, and these we were obliged to replace in a hurry by Italian brande, or folding bedsteads, of which more anon.

The steamer agent had written us that the Zara boats left Ancona at “0.30 Wednesday,” so of course we expected to leave next day, August the eighth. We had yet to learn, however, that at Ancona “0.30 Wednesday” means Wednesday night, or really Thursday morning, so we were let in for a second day at Ancona. However, a couple of days can be spent pleasantly enough in the quiet Italian seaport. The forts, the harbour, and, if one must say it, the glare, are provocative of recollections of Malta. The two bathing establishments are excellently managed, and it is a capital idea to be able to follow up one’s bathe by lunching at a table close to the sea. In fact, especially as the heat was very great, one would willingly have spent the whole day at one of these places, had they only provided a decent reading-room in addition. But literature is not an Italian want ; nor, I may add, are comfortable lounging-chairs.

The heat and drought had lasted over two months, we were told, so we were decidedly unfortunate to have to go aboard, as we did after dinner on Wednesday, in the most terrific rain. Being wet through, we thought we could do no better than turn in, which we did. I woke at the familiar sound of the siren, and, though I did not look at my watch, I fancy we sailed fairly punctually. “Now,” thought I, “it is a clear run to Dalmatia.”

Between six and seven I was on deck, and found the steamer, Barion by name, going about eight knots among an archipelago of barren-looking Dalmatian scoglie. This word is applied equally to the large islands and to the little ones, and even to the mere reefs. The sea was dead calm, and the morning bright and hot, so that there was no reason to suppose that we should meet with the slightest difficulty during the remainder of our voyage. We sat down on deck, where most of our fellow-passengers were assembled, and waited for our coffee to be announced.

All at once we heard a shout ; the engines stopped, and the rattle of a cable through its hawse-hole followed, accompanied by profuse Italian language, mostly bad. Going to the side, I saw that the ship had been steered for a channel some forty yards wide, between a long island (Melada) to port and a barren rock to starboard. Through this passage the water ran in a very broken manner, ominously suggestive of shallow water and a strong current.

Now we are going astern, and slowly, slowly the ship heads to the southward, her screw not five yards from the dry rocks on shore. Nothing but the knowledge of the precipitous nature of the coast of these islands warrants the execution of this otherwise perilous manœuvre. At last the bow swings clear, the anchor is catted and fished, we pass round the little scoglia, and, finding our proper channel on its southern side, steam cheerily through. In two hours we are at Zara.

Zara, or, to give it it...