![]()

CHAPTER ONE

THE ORIGIN AND DEVELOPMENT OF THE DETENTION CENTRES IN ENGLAND

THE Criminal Justice Act of 1948 abolished the sentence of corporal punishment and limited the power of the courts to commit to prison offenders under the age of twenty-one. These reductions in the armoury of the criminal courts were made good by the sentence of detention in a detention centre and, to some extent, by orders to attend an attendance centre. Although the Act of 1948 had its origins in the Criminal Justice Bill of 1938, which had reached an advanced stage in its passage through Parliament before it was put aside in 1939 owing to preparations for war, there were, in fact, no provisions for the setting up of detention centres in this earlier Bill. It was thought at that time that the proper treatment of young offenders could be accomplished by residential hostels (Howard Houses) and attendance centres.

In 1947, the Home Secretary, Mr. Chuter Ede, introducing the new Criminal Justice Bill, explained the function of a detention centre:

‘It provides for the young offender for whom a fine or probation order would be inadequate, but who does not require the prolonged period of training which is given by an approved school or a borstal institution. There is a type of offender to whom it seems necessary to give a short but sharp reminder that he is getting into ways that will inevitably lead him into disaster.’1

During the debate that followed, there was little discussion of the purpose and methods of the new institutions;2 attention was concentrated on the possibility of the restriction or abolition of the death sentence, on the abolition of corporal punishment and the treatment of younger offenders, especially in approved schools. When the Bill reached the Lords it was left to Lord Templewood, who as Sir Samuel Hoare had been responsible for the earlier proposals, to ask whether detention in a detention centre would, in fact, be anything else but imprisonment. In this he was speaking for the Magistrates Association as well as for himself, and, on their behalf also, he suggested that the attendance centres and residential hostels which had been outlined in the 1938 Bill would be sufficient to provide ‘a quick, sharp punishment of the kind that would not mean a break, or a serious break in the young offender’s life’.3 He agreed, however, to await events and see how the new penal experiment turned out.

As it finally reached the statute book, the new measure defined within broad limits the kind of offender for whom a sentence of detention was designed. First, the offence committed must be one for which a term of imprisonment could have been imposed. (This is a very wide definition since nearly every statutory offence carries, as its maximum penalty, a sentence of imprisonment. Wilful damage, offences of drunkenness and disorderly behaviour. all forms and degrees of larceny are punishable in this way.) Second, the offender must be over fourteen and under twenty-one years of age. Third, no offender who has served a borstal or prison sentence may be sentenced to detention. Fourth, no offender may be so sentenced unless the court has considered every other method of dealing with him and has found them inappropriate. For offenders who satisfied these four requirements the Prison Commission prepared to establish the new centres. In doing so they made the usual distinction between offenders under the age of seventeen who fall within the jurisdiction of the juvenile courts, and those between the ages of seventeen and twenty-one who are subjected to the rigour of adult criminal procedure. Since the increase in crime in 1951 was particularly marked in the age-group fourteen to seventeen, they decided to try out the new penal institution by opening a junior centre.

In 1952 the first detention centre for boys of fourteen and under seventeen years of age was opened at Campsfield House, Kidlington near Oxford. At first the regime was exacting and severe so that criticisms were immediately levelled at this institution on the grounds that it was harsh, unconstructive and ill-adapted to further the aims of any treatment prescribed by a juvenile court. Such views, common among social workers and social scientists, found expression in this forthright denial of its usefulness.

So far as I understand this so-called shock treatment, it depends upon the denial of human contact between the boy and members of the staff; in my judgement it runs counter to all the most hopeful developments in the treatment of delinquency. This, after all, is what the boy expects of society and in the Detention Centre, society duly obliges by providing it; the Centre offers no challenge to the boy and seeks no response from him other than obedience.4

The Prison Commissioners Report of 1952 acknowledged the existence of such criticism, but emphasized once more that the first aim of the new institutions was deterrence.5 Nevertheless, some changes were made in the severity of the regime and ‘there was a noticeable “mellowing” in the atmosphere of the Centre’.6 Probation officers, however, and social workers generally, still withheld approval from a penal measure that was enforceable by juvenile courts, that was too short for real treatment, and that had no satisfactory provisions for after-care. It is interesting to speculate whether criticism would have been so violent or so sustained if the first detention centre to be opened had been a senior centre for offenders over the age of seventeen.

Despite the volume of criticism, a second centre, this time for older offenders, was opened at Blantyre House, near Goudhurst in August 1954, and the courts made immediate use of the new facility. Committals to both centres were, however, rather haphazard until a study of the results of the sentence was published. This showed that, in terms of reconvictions, at least, the effect of detention upon ex-approved schoolboys and upon those whose criminal behaviour was long-lasting was not good enough to justify its continued use in such cases.7

On the basis of this study and in answer to the expressions of doubt about the usefulness of detention, efforts were made to ensure a better selection of offenders for this form of treatment. A Home Office circular gave advice to courts about the kind of offender most likely to respond to detention. Meanwhile, public anxiety about the growing criminality of the age-group seventeen to twenty-one led judges and magistrates to press for the opening of more senior centres. A second one was, therefore, opened early in 1957. This was at Werrington in Staffordshire and it received offenders from the northern and midland courts. Accommodation was now available for 142 young men between the ages of seventeen and twenty-one and 600 offenders could be received each year. This was not yet enough to provide an alternative to all sentences of imprisonment for men of this age-group. Moreover, the whole question of the treatment of offenders committed to penal institutions for short terms had been referred to the Advisory Council on the Treatment of Offenders and their Report on the Alternatives to Short Term Imprisonment8 was expected to indicate the trend of informed opinion at that time. The Advisory Council had considered what steps could be taken to reduce the number of committals to prison for periods of less than six months; its recommendations included the imposition of heavier fines, the use of supervision when time was allowed for payment, the provision of attendance centres for offenders over seventeen and the speedy implementation of the provisions of the Criminal Justice Act for remand centres. There was no mention of detention in a detention centre although the senior centre at Goudhurst had been open for more than a year when the committee of the Council began its enquiries. The senior attendance centre recommended by the Advisory Council was opened in Manchester in 1958. This, unlike the junior centre, was administered and staffed by the Prison Commission. Obviously, however, official policy was moving towards a solution of the problem of the treatment of young offenders that would make extensive use of senior detention centres. In 1958 the Advisory Council was asked to comment on specific proposals for the sentencing of offenders under the age of twenty-one. These were, first, that sentences under six months should be served in detention centres; second, that sentences between six months and two years should be indeterminate and be served in borstal type institutions and third, that imprisonment should be available as a sentence for offenders under twenty-one only when a term of three years or more was thought to be appropriate.

Before the Council examined these proposals in detail, the Home Secretary published, early in 1959, the White Paper on ‘Penal Practice in a Changing Society’.9 This contained the proposals for the treatment of young offenders which are outlined above. The White Paper, however, attracted little attention and what reaction there was, was generally favourable.10 The seal of approval was finally set upon this new venture in penal policy and administration by the full Report of the Advisory Council which said ‘the deficiencies of short sentences of imprisonment have, to a great extent, been overcome in detention centres’.11 At the same time, the Report stressed that ‘the penal treatment of young offenders should be primarily remedial’ and claimed that ‘the system has already shown some flexibility in expanding the original conception of a regime based primarily on deterrence to include elements of positive training’.12

With this powerful backing and little adverse public comment, a new Criminal Justice Bill was introduced early in 1960 containing provisions for the ultimate replacement of the majority of prison sentences for offenders under the age of twenty-one by sentences of detention, and the establishment of a system based on a shortened borstal sentence for periods between six months and two years. Sentences of over three years remained available for grave crimes and for offenders for whom such long terms of imprisonment seemed necessary. There was little alteration in these provisions during the passage of the Bill through both Houses.

The debate outside Parliament centred round the possible differences between detention centres and prisons. It had been demonstrated that detention in a detention centre served a useful purpose for certain selected offenders.13 It was argued that it could not, with continued good effect, be used indiscriminately. A second objection was to the length of sentences of detention. Sentences of three months and six months were not easy to integrate within one centre; under the Bill it would be possible, by a system of cumulative sentences and orders, for an offender to be sentenced to nine months’ detention. In contrast, the Report of the Scottish Advisory Council on the Treatment of Offenders recommended a uniform sentence of three months.14

The provisions for statutory after-care—a long-felt need—received a whole-hearted welcome, although there was some discussion about the treatment of those who broke the conditions of their supervision after release. The provisions of the 1961 Act involve the return of the offender to the centre for the unexpired portion of his sentence or for fourteen days, whichever is the greater. There does not seem to be any sound alternative to this solution but it will be noted that detention centres will, when the provisions come into effect, be able to receive some offenders for periods of fourteen days in addition to those sentenced for periods of three to nine months. It remains to be seen whether the new provisions for after-care will out-weigh the disadvantages of large variations in the lengths of sentence.

Since detention centres, borstal institutions and prisons are now to be used as alternative forms of penal institutions for young offenders under the age of twenty-one some comparison of the recent committals to each of those types of institution might prove useful.

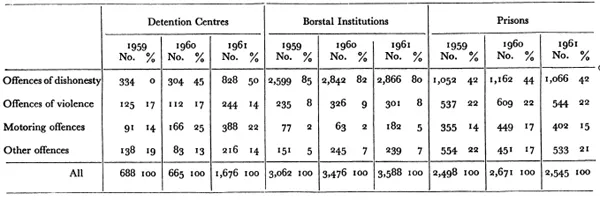

Table 115 shows the offences for which young men were sentenced to detention, to borstal and to prison for the years 1959, 1960 and 1961. There is a marked difference between the kind of offences committed by those who were sentenced to borstal and those who were sentenced to detention and imprisonment. Clearly the longer training provided by borstal institutions is thought to be more suitable for dishonest offenders while those found guilty of offences of violence are expected to be amenable to the deterrent regimes of detention centres and prisons.

Table 1: Analysis of the offences of offenders sentenced to detention, borstal training and imprisonment in the years 1959 1960 and 1961

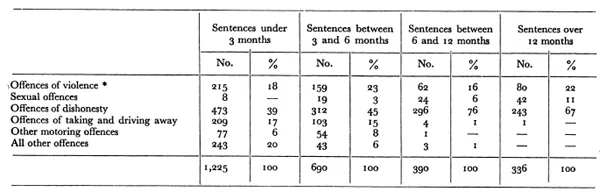

Table 2: Length of sentence, analysed by the offence committed, of male offenders aged 17–21 sentenced to imprisonment in 1960

* Offences of violence include all assaults, indictable and otherwise, actual, grievous bodily harm and murder.

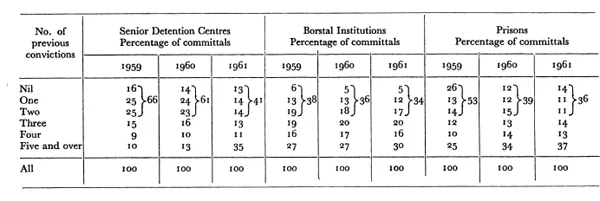

Table 3: Previous convictions of male offenders aged 17–21 sentenced to borstal training, imprisonment and detention in a detention centre in 1959, 1960 and 1961

The similarity between the type of offence com...