![]()

PART I

INTRODUCTION

![]()

1. INTRODUCTION

Anneke B. Mulder-Bakker in collaboration with Mireille Madou(iconograhy)

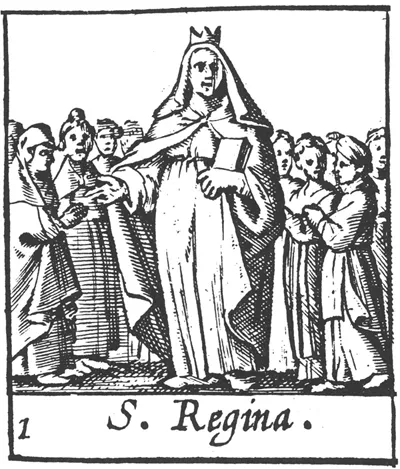

In his Legends of the Saints (Generate Legenden der Heiligen), the founder of modern hagiographical research Heribert Rosweyde (1569–1629) described the life of Saint Regina. Published in 1619, Rosweyde’s Vita is the first known account of her life. According to this, Regina, a noble Saxon woman, wife of Count Adalbert of Oostervant, was the epitome of a saintly mother (fig. 1.1). She gave birth to ten daughters, who, carefully nurtured in religion by the saint, all became consecrated virgins of God. They entered the monastery their mother founded for them in Denain, part of Adalbert’s territory in what is now Northern France. Her daughter Ragenfreda was its first abbess and Regina herself was buried there.1

Figure 1.1 Saint Regina and her ten virgin daughters. Engraving in Heribert Rosweyde, Generale Legende (Antwerp, 1649) (U.B. Groningen)

We could cynically remark that Regina as a married woman practiced what the Church Father Jerome preached: the only merit a wife could aim for was to bring forth pious virgins. In the Generale Legende, however, Saint Regina has more to her credit than childbearing alone. The name Regina was fit for this saint, so writes Rosweyde, for she was not only royal by birth, but also in character. Furthermore, she had devoted herself to Mary, the Queen of Heaven. She behaved as a woman of rank and quality should: she was an obedient daughter, a submissive wife, and a good mother. Together with her husband, she lived a pious life and did many works of charity. For her, marital love and love for God were parts of one whole.2 In reward, God bestowed upon Regina the blessing of wealth in goods and property and an offspring of ten virgin daughters. Regina seems to outdo Saint Anne, who in the course of the Middle Ages became (only) thrice a mother, as Brandenbarg explains in the first study in this collection.

From the eleventh century on, a modest-sized local cult of Saint Regina can be traced, whereby lectiones were read in the monastery of Denain on her feast day, the first of July. Rosweyde based his epitomy on these readings. In historical sources, however, there is neither trace of Regina, nor of her husband Count Adalbert. The only documented personage is Ragenfreda, who appears in a charter of 877 as foundress and first abbess of the Denain monastery. Regina appears to be a fiction, a legend which provided abbess Ragenfreda with holy antecedents.3

Such a phantasm is intriguing for our purposes. A figure like Saint Regina represents all that clerical authors such as Rosweyde believed an ideal mother to be: she is a stereotype of the mother saint. Like Saint Anne, who also received a curriculum vitae of her own in the transition from the medieval to the early modern period, Regina was a model saintly mother. Her Life encapsulates the ideology of sanctified motherhood in the late Middle Ages and early modern period.

It is significant that to introduce Sanctity and Motherhood I must resort to a fiction like Saint Regina. The usual corpus of “sacred biographies”4 contains almost no mother saints, that is, saints whose sanctity is based on motherhood. One may cite the overwhelming popular Virgin Mother Mary and her mother Saint Anne, along with the complete Holy Kinship, but the life stories of these mother saints are also essentially phantasms. Beyond Mary and Anne, both sanctified for their role of mother to key figures in salvation history, what examples of mother saints do we have? There were, of course, saints who were mothers, but they were honored at the altar despite rather than because of their children. There are moreover very few of these.

Delooz, in his sociological studies of saints, found but sixteen married among canonized saints, of whom five were parents, three women and two men. Weinstein and Bell came up with the same number in their well-known study: indeed, they drew their sample of saints from Delooz’s corpus and studied them in more detail. In the later Middle Ages it appears that more women, and among them more married women and mothers, were canonized. Vauchez, who studied all the canonization trials of the thirteenth to sixteenth centuries came up with 25% or even 28% in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries5—Elizabeth of Thuringia is the first, Birgitta of Sweden the most famous of these late medieval saints, both studied in this volume. Why are there so few? And what is more, can we really compare these few to the mother saints Mary and Anne? Are we, in other words, justified to term them mother saints, as defined in this volume? As I will argue below, it seems more apt to term them holy mothers, that is holy women whose public role in society was based on their status as spouse and mother; it was this status of motherhood that gave them entrance to the public sphere (in a similar way as entering the job-market does now) and this opened for them the road to sanctitude.

The articles here presented offer some new food for thought. Firstly, we have the studies of Ida of Boulogne, Ivetta of Huy, Elizabeth of Thuringia, and Birgitta of Sweden. Ivetta of Huy, an early thirteenth-century patrician widow, whom I have studied in this volume, appears to have continued an intense contact with her family after she became a recluse. Indeed, after the ritual of enclosure Ivetta was seen as a mouthpiece of God; she became a sapientissima mater for community, clergy, and kin. In her study of Elizabeth of Thuringia, Petrakopoulos notes that there is a discrepancy between the role marriage and motherhood played in the life of Elizabeth and their role in the later symbolization of the saint. Marriage and motherhood did not hinder Elizabeth from attaining holy charisma in her lifetime, but in hagiography these aspects are not portrayed as an integral part of her sanctity. Petrakopoulos can ascertain this because of the nature of the sources about Elizabeth: in her case we do not have to rely on polished images presented by learned Church clergy. This is something to remember. Nieuwland shows how Birgitta of Sweden imparts to her readers her personal ideas and conceptions, her worries and doubts. She shows us how Birgitta spontaneously uses maternal imagery to describe the concept of God, and she also shows how Birgitta finds succour in the Holy Mother Mary during labor and how she learns from Anna to depend on saints who themselves have been mothers. In the lives of Ivetta, Elizabeth and Birgitta, the links between holiness and motherhood are apparent, in their Vitae, much less so. Ida of Boulogne, studied by Nip, is the only woman who owed her sainthood to her sons, the famous leaders of the First Crusade and the first Kings of Jerusalem. She is rightly called a mother saint. To distinguish her from the others, I allot the term holy mothers to the latter.

Secondly, in late medieval sources religious phenomena are described which had until then no recorded history, religious phenomena which concern sanctity and motherhood. The studies of Brandenbarg and Tilmans show that late medieval people, even learned humanists, honored Mary and Anne in an immensely popular cult. These mother saints somehow answered the devotional needs of medieval people, and their cults induce us to reconsider the link between sanctity and motherhood.

We need to take a critical look at the nature of the sources. Medieval history is a history made up of several layers. At the bottom we have the chaotic and dispersed traces of life: artifacts like a kitchen spoon or a child’s shoe, which have survived by accident and were not meant to tell a story. There are also layers made up for the needs of the moment, texts to inform, to instruct, to recreate; or for the short term memory, such as city accounts. Hagiography and historiography on the other hand were intended to preserve events of the past for the long term, and often enough the writers explain they are writing these events down because they should not be forgotten. These sources also serve the needs of the moment, but in a different way. Asking just how they did, what they selected for preservation and what they chose to omit, in other words, a critical assessment of these sources, is a crucial part of our work.

Our sources, however, have not only undergone processes of omission and selection during their creation. There is also the process of transmission, which can be happenstance, casual, or, and for hagiography this is of vital importance, a conscious, concerted, group effort to collect and preserve. As we will see, the Acta Sanctorum, a source on which medievalists rely, is in fact a collection of saints’ lives of the seventeenth and later centuries. Thus Counter-Reformational choices also color our view of medieval history, and in the present case, of the relation between sanctity and motherhood. Another factor contributing to the selective view sources can give us is that different groups in medieval society reached different levels of literacy and subsequently have left different degrees of documentation. In the early Middle Ages especially, the pen was wielded by clergy and monks. Only that which pertained to them was set down on parchment. Other sectors of society—and this applies as well for the later Middle Ages—were predominantly oral; they left hardly any written records. Studies in the field of institutional history show that it is especially new developments which are documented, new developments in which the top ranks, men in other words, played an important role. Areas which were ruled by tradition, precisely those areas in which women played an important and accepted role as wives and mothers of future generations, have much less resonance in written sources. Why record a tradition? It is, after all, common knowledge. At the very best we find these female roles in chivalric epic or pedagogical tracts.6 However, the yield of sources from the late Middle Ages is much richer: there are more of them, and they originate from broader segments of society. On the basis of what they tell us, we can do some guesswork for earlier periods.

In this introduction I will pursue some of the topics which present themselves in the above: a) a second inventory of the sources which we have, this time the iconography of saintly mothers, which will help us set the geographic boundaries for the studies in this volume, b) the nature of the hagiographical selection included in the Acta Sanctorum, c) characteristics of the saints’ lives which have been handed down to us and the discrepancies between holy persons and saints, and d) the cultural force of the laity.

This introduction does not allow for an exhaustive treatment of these topics. Rather it will serve as a preliminary survey of the terrain, in which various problems are charted. Clarissa Atkinson will in her conclusion analyze and comment on the broader trends and developments which come to the fore in the articles in this collection.

A SECOND SURVEY: THE ICONOGRAPHIC DOSSIER

Next to hagiography, iconographic sources can give us a perspective on the medieval history of sanctity and motherhood. Mireille Madou,7 the art historian who made an inventory of the visual material about saintly mothers for this volume, confirms that every search for mother saints in the visual arts inevitably leads to the countless portrayals of Mary with her child Jesus. Almost as inevitably the search leads to Saint Anne, often surrounded by the Holy Kinship. The iconography of these saints succinctly reveals the essence of their sanctity: they are mothers of the key figures in salvation history; their attributes are these children. No other saints are iconographically distinguished by their children as mother saints in the way Mary and Anne are.

During the times of the persecutions in the early Church, many married women and mothers were martyred. Only four of them, however, and then only from the twelfth century onwards, were occasionally depicted with their children. The other mother martyrs were celebrated in the liturgy, represented in frescoes and altarpieces, sculpted in wood or stone, but without their children. De Nie, in her contribution, calls to attention Perpetua, the mother of a young child, who was thrown into prison with her pregnant slave Felicitas. There Felicitas bore her child. In 203 they suffered a gruesome martyrdom. Neither saint is depicted with child. It is again among the legendary martyrs that we find iconographic links between sanctity and motherhood, saints such as Julita and her three-year-old son Quiricius, who supposedly suffered under Diocletian, or Felicitas and her seven sons, and Symphorosa, also with her sevensome. The historical trustworthiness of their lives is with reason subject to doubt. Their Passios show a remarkable similarity to the seven brethren and their mother of 2 Mace. 7. Saint Sophia and her daughters Fides, Spes, and Caritas are all martyrs who belong to the world of allegory. Precisely these saints are shown with children: Julita, Felicitas and Sym...