![]()

1

Septimius Severus and the Struggle for Power

Lucius Septimius Severus, who was emperor from 193 to 211, had greater difficulty than anyone before him in seizing the throne. There was a certain resemblance between 193 and 69, when the Julio-Claudian house had come to an end and there had been civil wars. But this time it was even worse, and the task of Septimius Severus was severer than Vespasian’s (69-79). It was, indeed, a remarkable feat that Septimius succeeded in reaching the throne at all. He did so by putting down not only the transient emperor who came before him, Didius Julianus, but by suppressing two formidable rivals, Pescennius Niger and Clodius Albinus.

Septimius Severus (Plates 3-4) had been born in 145 at Lepcis Magna (Lebda) in Tripolitana. He was given the name of his paternal grandfather, who was probably a man of Carthaginian (Punic) origin (perhaps with some Berber blood), and had migrated from Lepcis Magna to Italy in the last years of the first century AD, achieving promotion to equestrian (knightly) status. Septimius’s mother Fulvia Pia may have come from an Italian family which moved to north Africa.1

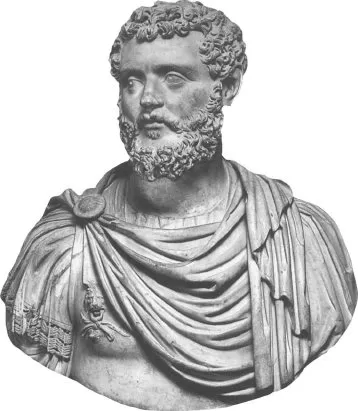

Plate 3 Septimius Severns. Antike Sammlungen, Glyptothek, Munich (Alinari) The busts of Septimius Severns, which are fairly numerous, combine a backward-looking, Antonine appearance with certain features that betoken the future : in fact, they stand for the new Severan epoch. The general impression is Antonine - we are expected to see Septimius as the rightful heir and successor of Antoninus Pius and Marcus Aurelius, to whose family he, fictitiously, claimed to belong. Yet the hair-style is more akin to modern times, with echoes of the Egyptian god Serapis. Nevertheless, if Septimius possessed any markedly un-Roman features, they are not made apparent on these busts.

Plate 4 Bronze sestertius of Septimius Severns. M . Grant, The World of Rome (1960), plate 9 (British Museum)

Septimius assumes the name of Pertinax, whose memory he honoured, and is IMPERATOR for the fourth time (194-5) (L. SEPT. SEV. PERT. AVG. IMP IIII) . He also wears military uniform, a fitting tribute to his own military success in putting down Pescennius Niger (as he later defeated Clodius Albinus). (And on the reverse appears AFRICA, which was his homeland, since he came from Lepcis Magna in Tripolitana. Septimius enriched Africa (not least his home town) with many buildings, and here he celebrates his country, which is personified wearing an elephant-skin head-dress, and apparently holding ears of corn in a fold of her robe. At her feet, partly seen, is a lion . On other coins Septimius honours the gods who received special veneration in Africa and his own family, Hercules and Bacchus.)

Septimius became a member of the Roman senate (perhaps in about 173), held the governorships of Gallia Lugdunensis and Sicily, and was then consul (190) and governor of Upper Pannonia. After the short reign of Pertinax in 193, followed by the accession of Didius Julianus, Septimius was proclaimed emperor by his legions (see n. 4), apparently at Carnuntum (Petronell) - or possibly at Savaria (Szombathely), also in Upper Pannonia - while Pescennius Niger received a similar salutation in the east.

After granting the title of Caesar to Clodius Albinus, governor of Britain, Septimius set out for the east against this rival claimant, Pescennius Niger. Decisive victories over Pescennius Niger were followed by pumtrve expeditions against the Osrhoeni and other Parthian vassals who had helped Niger. Before returning to Europe to fight against Albinus, Septimius raised his son Caracalla to the rank of Caesar in Albinus’s place and adopted himself into the family of the Antonines (196).

The issue against Albinus was settled in a battle near. Lugdunum (Lyon) (February 197). After a short stay in Rome, Septimius moved east to retaliate against Parthia for its at least verbal support of Niger. A campaign culminated in the fall of Ctesiphon (perhaps in December 197). After two abortive attacks on the desert fortress of Hatra (Al-Hadr) the war ended with the annexation of Osrhoene and Mesopotamia by the Romans (199). The next two years were spent by Septimius in Syria and Egypt. On 1 January 202 he and his elder son Caracalla became joint consuls at Antioch. Then Septimius and his family returned to Rome. Septimius spent much of the next six years in Italy, but visited Africa in 203-5, and perhaps in 208 as well. In 208 he set out with his wife and two sons, Caracalla and Geta, for Britain. In the hope of intimidating the Caledonians Scotland was invaded. The Roman losses, however, were severe, and a temporary peace was patched up in the summer of 210. Worn out by sickness and broken in spirit by Caracalla’s unfilial conduct, which consorted badly with intentions of founding a dynasty, Septimius died at Eburacum (York) in 211.

How much should he be regarded as an Africani?2 Opinions differ. Did he have an African accent? Probably; his sister spoke with one, and he had, as we saw, some Punic (if not Berber) blood. Was he dark-skinned, or more dark-skinned than the Italians? John Malalas says he was. But we cannot be sure. There is a tendency nowadays to say that the Africitas of Septimius has been over-estimated. Yet it was from Africa that he came (Plate 4), and this influenced his attitude towards Italy (Chapter 5).

Something more must be said about Septimius’s accession. He had been hailed emperor as soon as the news of the succession of Didius Julianus arrived, and took the name of Pertinax in honour of that emperor’s predecessor. Septimius had, locally, administered the oath of allegiance to Pertinax.3 It was on the accession of Didius Julianus, with the support of nearly all the Danubian and Rhenish legions,4 that Septimius made his dash for Rome, where he spent thirty days in June (from the 2nd) and early July of 193 - between three and four months after his initial proclamation. It seems very possible that Pertinax had intended him to be his heir.5

But Septimius’s claim to the imperial throne was contested by Pescennius Niger in the east, for which Septimius left promptly in order to deal with him. Gaius Pescennius Niger was born in about AD 135 (or a little later), and came from an Italian family of equestrian (knightly) rank.6 Promoted into the senate by Commodus, he fought against the Sarmatians in Dacia in 183, and became consul. Then, in 190, he was appointed to the governorship of Syria, where his lavish output on public entertainments made him popular. When he obtained news, in 193, of the assassination of Pertinax and the problems that were besetting Didius julianus, he allowed himself to be proclaimed emperor by his soldiers at Antioch - at approximately the time of Septimius Severus’s proclamation in Upper Pannonia. (Like Septimius, he had probably already intended to seize the throne once Pertinax was out of the way.) The character of Pescennius Niger has been disputed. Discipline and austerity are ascribed to him. But it is plausible to agree that he was neither particularly good nor particularly bad, although we have, of course, mainly his victorious enemy’s account.7

All the nine legions stationed in the east declared for Niger. And he gained the support (though no troops, for internal reasons) of King Vologases V of Parthia (cf. above; and Chapter 5). Within Europe, too, Niger obtained the allegiance of Byzantium - the later Constantinople (Istanbul) - and intended to occupy another city, Perinthus (Marmaraereǧlisi, Ereǧli), to ensure him the control of the main land routes. But Septimius Severus, arriving from Rome, sent ahead an advance guard which captured Perinthus. And then he proceeded to besiege Byzantium. Niger’s commander-in-chief, Asellius Aemilianus, was defeated across the Bosphorus near Cyzicus (Balkiz) and again in the neighbourhood of Nicaea (Iznik), in the narrow passes west of the city.8 With what was left of his army Niger withdrew eastwards across the Taurus (Toros) mountains. However, his rearguard was swept aside by the enemy, who broke through the Cilician Gates (Külek Boǧazi), endangering Antioch itself. In order to stop their advance Pescennius Niger moved forward to Issus (Deli Çay), on the borders of Syria and Asia Minor. Nevertheless, his army was again defeated there.9 He returned to Antioch. But when news came that Septimius was not far away he evacuated the city and fled eastwards towards the Euphrates. Before Pescennius Niger was able to cross the river, however, he was overtaken and killed (195). Byzantium, discouraged, surrendered. Its siege had lasted for more than two years: the city seems to have fallen late in 195, perhaps in December, although an earlier month is not out of the question.

Pescennius Niger had been distinctly popular at Rome, which caused Septimius particular worry. Niger’s coins of various eastern mints,10 in addition to displaying eastern themes, show that he had intended to inaugurate a new Golden Age, linked with Augustus. His key title was ‘Justus’ - indicating straight and faithful dealing: though how far this was translated into action we cannot tell. It is probably fair enough to conclude that Septimius won the war against him by taking advantage of Pescennius Niger’s military mistakes. After that fight was over Septimius embarked on the First Parthian War (Chapter 5), partly in order to suppress Barsemius of Hatra, who (like Parthia, it was said: cf. above), had supported Pescennius Niger.

But when Septimius came back to Rome - as we learn from the coins that he did - a sinister incident occurred when the populace ‘indulged in the most open lamentations’ (about the imminent war against Albinus, governor of Britain).

There had assembled. . . an untold multitude and they had watched the chariots racing. .. without applauding, as was their custom, any of the contestants at all. But when these races were over and the charioteers were about to begin another event, they first enjoined silence upon one another and then suddenly all clapped their hands at the same moment and also joined in a shout, praying for good fortune for the public welfare.

This was what they first cried out. Then, applying the terms ‘Queen’ and ‘Immortal’ to Rome, they shouted: ‘How long are we to suffer such things?’ and ‘How long are we to be waging war?’ ...

This demonstration was one thing that increased our apprehensions still more.

That was said by a Senator, Dio Cassius (Appendix) but: it increased the apprehensions of Septimius Severns to an even greater degree. It was, for him, a nightmare come true. The emperors were always afraid of trouble from the people of Rome - hence their repeated acts of generosity towards the metropolitan population (Chapter 7). Indeed, they feared, very often, that these people would bring them down: though in this they were wrong, because it was usually the army that did so. Perhaps that was because the emperors treated the civilian populace of Rome so generously. Or, more probably, the fear was just unwarranted. This demonstration against Septimius Severus may well, as Dio Cassius and other ancient historians hint, have been organized and orchestrated by the supporters of Clodius Albinus in the city, who were numerous, not least in the senate.

Nevertheless, at about the turn of the year, Septimius broke with Albinus, whether unwillingly or deliberately we cannot tell,11 and left Rome to contest his claim to the imperial throne.

Clodius Albinus (Decimus Clodius Septimius Albinus) was probably born between 140 and 150. He was said to have come from a rich (noble?) family of Hadrumetum (Sousse) in north Africa, but this remains doubtful. He seems to have started his official career as an eques (knight). But he became a member of the senate during the later years of Marcus Aurelius, to whom, as governor of Bithynia-Pontus, he remained loyal during the rebellion of Avidius Cassius in 175. Thereafter Albinus fought in Dacia (182-4), and may have been governor of Upper or Lower Germany. Consul around the year 190, he then obtained the governorship of Britain, where he had to deal with a turbulent garrison.12

Septimius Severus, when he claimed to be the successor of Didius Julianus in 193, freed his hands for the imminent war against his eastern rival Pescennius Niger by declaring Clodius Albinus to be Caesar. This title implied that he was destined to be Septimius’s successor. And the coinage of the time makes it clear that this was so.13 It might seem somewhat naive of Albinus to have trusted, apparently, the authenticity of this offer and to have, in consequence, accepted the offer, and thus, in 194, to have obtained a second consulship in absentia, keeping quiet for two years - although Septimius had two sons, Caracalla and Geta, whom he presumably intended, when they became old enough, to become his successors. However, Caracalla was at this stage only 5 years old, and Geta was even younger. And Clodius Albinus, whatever his doubts about Septimius’s motives, could well have hoped that he himself might become emperor if Septimius was defeated and killed in his forthcoming war against Pescennius Niger.

But it was Niger who was defeated and killed, and so Septimius survived. In 195 the relationship between him and Albinus was broken off (so that Caracalla became Caesar instead). In consequence Albinus, abandoning his allegiance to Septimius, had himself proclaimed Augustus, and was declared an enemy of the state by Septimius’s government. Yet Albinus’s cause was by no means hopeless. Not only had he, as we saw, many supporters at Rome, but he was also backed, for example, by the governor of Hispania Tarraconensis, Lucius Novius Rufus. It is not impossible that Albinus planned to march into Italy. For if he remained inactive, disaster was sure to follow, and he did not intend that this should happen.

So he sailed from ...