eBook - ePub

Encyclopedia of Animal Rights and Animal Welfare

Marc Bekoff, Carron A. Meaney, Marc Bekoff, Carron A. Meaney

This is a test

Share book

- 470 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Encyclopedia of Animal Rights and Animal Welfare

Marc Bekoff, Carron A. Meaney, Marc Bekoff, Carron A. Meaney

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Human beings' responsibility to and for their fellow animals has become an increasingly controversial subject. This book provides a provocative overview of the many different perspectives on the issues of animal rights and animal welfare in an easy-to-use encyclopedic format. Original contributions, from over 125 well-known philosophers, biologists, and psychologists in this field, create a well-balanced and multi-disciplinary work. Users will be able to examine critically the varied angles and arguments and gain a better understanding of the history and development of animal rights and animal protectionist movements around the world. Outstanding Reference Source

Best Reference Source

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Encyclopedia of Animal Rights and Animal Welfare an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Encyclopedia of Animal Rights and Animal Welfare by Marc Bekoff, Carron A. Meaney, Marc Bekoff, Carron A. Meaney in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Scienze sociali & Sociologia. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

A

ACTIVISM FOR ANIMALS

Animal protection as a social movement is a modern development, arising in England early in the 18th century. From the beginning, activists working to protect animals have enlisted the support of wealthy and powerful individuals whose political influence and economic privilege have greatly advanced the animal-protection agenda. At the same time, a high degree of tension has always existed between those promoting gradual improvement and proponents of revolutionary change. Societies for the protection of animals were formed in both England and the United States in connection with the passing of the first animal protection legislation (see AMERICAN SOCIETY FOR THE PREVENTION OF CRUELTY TO ANIMALS; ROYAL SOCIETY FOR THE PREVENTION OF CRUELTY TO ANIMALS). Those who fought for this legislation were often the same individuals who formed the societies.

Some authors draw a sharp distinction between the humane movement and activism opposing the use of animals in science (the antivivisection movement; see ANTIVIVISECTIONISM), which arose decades later, pointing to both ideological and class differences between the two. However, ideology and class divided individuals within the antivivisection movement as well, as demonstrated most acutely in the rivalry between Anna Kingsford and Frances Power Cobbe,* the two most important figures in 19th-century British antivivisection. While Kingsford, a physician, linked the suffering of laboratory animals with the suffering of “animals in the meat-trade, the fur-trade, in the hunting field, and in the barnyard,” Cobbe retained a single-minded focus on vivisection, continuing to wear furs and eat meat. Nonetheless, the two activists were equally intense in their opposition to the scientific use of animals and both refused to compromise or consider anything other than the immediate ending of the practice.

Victorian antivivisectionists tended to use the same methods of protest developed by other groups advocating social change. Foreshadowing contemporary “celebrity activism,” Cobbe enlisted the support of individuals prominent in law, government, and the church to lobby for the cause. Antivivisection and animal welfare organizations produced a huge volume of literature in the 19th century, including periodicals, advertisements, and tracts. Five antivivisection congresses drawing activists from all over Europe were held from 1898 to 1909, with the last culminating in a demonstration in London that included seven marching bands.

Louise Lind-af-Hageby* and Leisa Schartau, two Swedish medical students, anticipated the undercover investigations of 20th-century animal rights* groups by attending physiology demonstrations at University College, Kings College, and the University of London and then writing a book about their observations titled The Shambles of Science, which created an enormous outpouring of public revulsion. Nonetheless, the increasingly successful record of experimental medicine in developing vaccines and treating infectious diseases effectively killed public support for antivivisection until late in the 20th century.

Interest in animal protection began to peak once again following the publication of philosopher Peter Singer’s book Animal Liberation in 1975. Singer’s critical analysis of human exploitation of other animals, which he termed “speciesism,”* found a receptive audience and instigated an upsurge in animal-related activism that rivaled 19th-century efforts. Enormous sums of money were donated to existing organizations, and a number of new groups were soon founded, most notably People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals (PETA), which grew from 25 to 250,000 members during the 1980s.

Unlike their 19th-century predecessors, 20th-century activists could claim some clear victories. Henry Spira, head of the New York-based Animal Rights International, achieved antivivisection’s first major success by forcing the cessation of experiments on cats at the Museum of Natural History in New York City after over a year of protest in 1977. Spira’s Coalition to Abolish the Draize Test fought for and eventually achieved radical changes in product safety testing worldwide. In the standard Draize test, a liquid or solid substance is placed in one eye each of a group of rabbits, and changes in the cornea, conjunctiva, and iris are then observed and scored. Both injury and potential for recovery are noted. Consumer protests against widespread use of the Draize test created the momentum that led to the development of alternatives to many types of whole-animal testing. Campaigns against fur wearing led by PETA and other organizations resulted in significant drops in fur sales by the mid-1990s.

Despite its philosophical basis in ethics and its emphasis on compassion, animal protection also displayed a violent face in the activities of the Animal Liberation Front (ALF) and other radical groups. Arson, vandalism, and malicious destruction of property by animal rights activists from 1977 to 1993 resulted in damages of $7.75 million, leading the biomedical research community to press for the Animal Enterprise Protection Act, passed by Congress in August 1992. This legislation makes theft and destruction of property at a research facility a federal crime. In the final years of the 20th century, the focus of animal rights activism is shifting to factory farming* and the environmental, ethical, and health costs of a meat-based diet.

Selected Bibliography. French, R. D., Antivivisection and Medical Science in Victorian Society (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975); Hume, E. D., The Mind-Changers (London: Michael Joseph, 1939); Rowan, A. N., F. M. Loew, and J. C. Weer, The Animal Research Controversy: Protest, Process, and Public Policy (Boston: Center for Animals and Public Policy, 1995); Sperling, S., Animal Liberators: Research and Morality (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1988); Turner, J., Reckoning with the Beast: Animals, Pain, and Humanity in the Victorian Mind (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1980).

DEBORAH RUDACILLE

ADVERTISING, USE OF ANIMALS IN

The use of live animals in advertising takes many different forms. Domestic animals and wild animals are often trained for use in television commercials. While the advertising industry purports to adhere to standards set by the American Humane Association in regard to the treatment of animal “actors,” some would argue that the manipulation (i.e., training) of an animal for use in advertising is unethical. The use of wild animals in commercials is particularly controversial. Animal rights* advocates maintain that when an animal is shown in a setting that is completely unrelated to its natural environment, a message about that animal’s nature is conveyed that is both false and damaging to an accurate public understanding of the particular animal’s nature. Even when domestic animals are used in advertising in ways that portray them more accurately, such as domestic dogs* or cats* in some animal food commercials, many proponents of animal rights believe that the individual animals used are being exploited. Often, dogs or cats are dressed in human clothing, and cinematographic technology is used to make them appear to be dancing or performing other humanlike behaviors. This use of animals is considered to be demeaning and trivializing to individual animals and to animals in general.

Live animals have also been kept in cages and other enclosures for advertising purposes. Considerable attention has been given to the imprisonment of great apes such as gorillas in small cages in stores and shopping malls. The only argument in favor of such a use of animals is one that disclaims the fact that animals have any inherent rights at all and considers humans to have the right to employ an animal for any purpose that benefits a human being. In other words, this view argues that humans have the right to complete control and dominion over animals. From an animal rights perspective, this practice is abusive and unethical because it causes harm to an animal by restricting his or her freedom, places him or her in an unnatural setting, and isolates the animal from others of his or her kind.

The effect and implications of using images of animals in advertising are more subtle. Animals used to sell products and services that are aimed at children are usually shown as silly or “cute.” “Tony the Tiger” is just one example of an animal image with which we are all familiar and that has come to be closely associated with a particular food product marketed to children. Tigers, many would argue, should be valued as the wild and independent creatures that they are in nature and should not be portrayed as friendly purveyors of breakfast cereal. Although most people would view the use of animal images as harmless, many advocates of animal rights argue that these images exploit animals, contribute to the perpetuation of a view of animals that is paternalistic and trivializing, and ultimately contribute to a lack of respect for members of other species.

ANN B. WOLFE

ALTERNATIVES TO ANIMAL EXPERIMENTS

In the early 1970s, British antivivisectionists (see ANTIVIVISECTIONISM) established humane research charities with twin aims: to advance medical progress and to replace animal experiments with solely nonanimal methods. This was the first coordinated effort anywhere in the world to identify and develop alternative, nonanimal research as a serious scientific enterprise. Despite initial resistance from the scientific community, progress with alternative techniques has been dramatic. Animal experiments are being replaced by alternative methods, called nonanimal techniques, that range from the inanimate, such as computer systems and chemical tests, through research at the molecular and the cellular level to clinical research and population studies at the other end of the spectrum. Computer programs can offer insights into the action of new medicines on the basis of their molecular structures, even when they exist only in the chemist’s imagination. On a systems level, complex aspects of physiology and drug metabolism can also be modeled with computers. For example, there are computer programs that can predict, with 80% accuracy, whether or not a chemical may be metabolized by the liver into a cancer-causing substance.

Understanding basic processes of health and disease through use of human cells and tissues grown outside the body in laboratory cultures leads to better diagnosis and treatments. Rabies diagnosis used to require infecting mice* with the disease, inevitably causing suffering and death. A tissue-culture test has now saved many tens of thousands of mice and produces results in 4 rather than 35 days.

Human cell and tissue cultures, sometimes combined with silicon-chip technology and fluorescent dyes, are replacing animals in medical research and vaccine production. Cancer, Parkinson’s disease, diabetes, asthma, colitis, spinal injury, and multiple sclerosis are all being researched in the “test tube.” In the Netherlands, scientists have replaced lethal vaccine tests on guinea pigs with cell-culture alternatives. Sometimes, microscopic organisms such as bacteria and yeasts are simple analogues of a human system. For example, tests with bacterial cultures have partly replaced the use of rats and mice to determine whether chemicals cause cancer. As a result, many thousands of animals have been spared from chemical-induced tumors. Volunteer studies provide direct information about human health and disease. Cancer, heart disease, muscle disorders, epilepsy, arthritis, and psychiatric illness can be researched with new scanning and imaging techniques. Lasers and ultrasound probes can safely monitor the internal effects of some novel treatments.

Population studies of diet, lifestyle, and occupation have revealed causes of heart disease, stroke, cancer, osteoporosis, and birth defects. Diabetes, arthritis, and multiple sclerosis are among other major health problems for which population research is providing breakthroughs.

Today, nonanimal methods of research, testing, and teaching are widely accepted and increasingly implemented. Medical students can learn physiology and pharmacology from interactive computer models and self-experimentation, instead of using dogs* and rabbits; cell-culture tests are replacing experiments on mice and guinea pigs; studies of the brain are pursued safely in volunteers instead of through invasive research on monkeys. Nonanimal techniques allow us to save lives tomorrow without taking lives today.

Selected Bibliography. Langley, G. R. (Ed.), Animal Experimentation: The Consensus Changes (Basingstoke, England: Macmillan, 1989); Orlans, F. B., In the Name of Science: Issues in Responsible Animal Experimentation (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1993); Sharpe, R., Let’s Liberate Science: Humane Research for All Our Futures (Jenkin-town, PA: American Anti-Vivisection Society, 1992).

GILL LANGLEY

Reduction, Refinement, and Replacement (the Three Rs)

The concept of alternatives or the Three Rs, reduction, refinement, and replacement of laboratory animal use,* first appeared in a book by two British scientists, William M. S. Russell and Rex Burch, published in 1959 entitled The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique. The book was the report of their scientific study of humane techniques in laboratory animal experiments, commissioned by the Universities Federation for Animal Welfare (UFAW). Russell and Burch maintained that scientific excellence and the humane use of laboratory animals were inextricably linked and proceeded to define in detail how both of these goals could be achieved through reduction, refinement, and replacement of animal use. In 1978, physiologist David Smyth used the term “alternatives” to refer to the Three Rs. Since then, the Three Rs have become interchangeable with the word “alternatives.” In some circles, however, the word “alternatives” is understood to signify only replacement. Hence, in order to avoid possible misinterpretations, one of the Three Rs should precede the term “alternatives” when discussing specific methods (reduction alternative, refinement alternative, or replacement alternative).

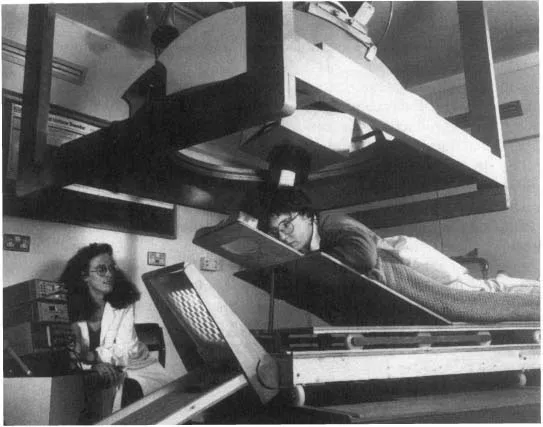

Alternatives to Animal Experiments. The MEG brain scanner is entirely noninvasive and is here being used to study photosensitive epilepsy in a volunteer. This is an alternative to distressing experiments on baboons. Source: Dr. Hadwen Trust for Humane Research, Clinical Neurophysiology Unit, Aston University, Birmingham, England.

A reduction alternative is a method that uses fewer animals to obtain the same amount of data or that allows more information to be obtained from a given number of animals. The goal of reduction alternatives is to decrease the total number of animals that must be used. In research, scientists can decrease the number of animals they use by more efficient planning of experiments and by more precise use of statistics to analyze their results. Researchers can also reduce the number of experimental animals by using ever-evolving cellular and molecular biological methods. These systems are sometimes more suitable for testing hypotheses and for gaining substantial information prior to conducting an animal experiment.

Refinement alternatives are methods that minimize animal pain* and distress* or that enhance animal well-being.* An important consideration in developing refinement alternatives is being able to assess the level of pain an animal is experiencing. In the absence of good objective measures of pain, it is appropriate to assume that if a procedure is painful to humans, it will also be painful to animals. Refinement alternatives include the use of analgesics and/or anesthetics to alleviate any potential pain. They also include the use of proper handling techniques and environment enrichment.* Such enrichment ranges from placing species-appropriate objects for play and exploration in animal cages to group housing of social species.

Replacement alternatives are methods that do not use live animals, such as in vitro systems. The term “in vitro” literally means “in glass” and refers to studies carried out on living material or components of living material cultured in petri dishes or in test tubes under defined conditions. These may be contrasted to “in vivo” studies, or those carried out “in the living animal.” Certa...