![]()

1 Introduction

This book is about poverty, and about one of its main causes – financial exclusion, the inability of many low-income people to build up their capital through access to fair-priced financial services. It asks why financial exclusion occurs, and discusses what can be done to get rid of it in the context of four British cities.

Background

As far back as 1942, a British government committed itself to the elimination of poverty. William Beveridge, the civil servant asked by the government to draft a plan which would achieve this, presented a report entitled Social Insurance and Allied Services, which was intended to provide everyone with a basic income on which they could decently live. But, he emphasised, the ending of poverty, in the sense of an income which falls below a decent level,1 ‘is only one of five giants on the road of reconstruction, and in some ways the easiest to attack. The others are Disease, Ignorance, Squalor and Idleness’.2 The other giants, indeed, were also attacked with vigour in the wake of the Beveridge report – through the National Health Service, through the 1944 Education Act which for the first time provided free secondary education, through a massive post-war rehousing programme and through a return, for the first time since 1914, to full employment. And the principal giant, income poverty, was very nearly slain within a decade. Having run at average levels in excess of 30 per cent of the adult population throughout the inter-war period,3 income poverty was estimated by the great pioneer investigator Seebohm Rowntree to have fallen below 5 per cent by 1950.4 Here, and in other industrialised countries, the ‘Welfare State’, as it quickly became known, offered a promise, sixty years ago, of social protection for everyone for as far ahead as anyone wished to look.

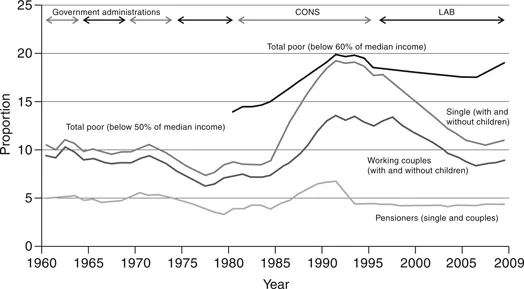

As we now know, things turned out differently. Two of the giants, unemployment and poverty itself, reared their heads again at the beginning of the 1980s (see Figure 1.1, below), as a consequence of governments discovering all round the world that two of the foundations on which Beveridge had built, full employment with stable prices, were not in the long run compatible. With unemployment and inflation both growing rapidly, the Beveridge principles were helpless, and the decision taken both in Britain and in other industrialised countries was to put the objective of stable prices first. In the process, governments discovered that poverty was a more complex thing than it had been visualised in the 1940s and 1950s. One reason for this was the problem of the ‘cycle of deprivation’ or of the persistence of poverty: some people, in spite of the best efforts of the welfare state, remained caught in a poverty trap by the interaction of a multiplicity of factors – family break-up, multiple children, eviction from insecure tenure, low education, ill health, high prices of consumer goods, an inability to save or borrow to finance these purchases, an inability to get back into work. Several of these impacts were not chronicled by Beveridge, and some of them, having once locked the sufferer into chronic poverty, were then passed on to the next generation. Indeed poverty might occur, not just in spite of, but because of the best efforts of the welfare state. One illustration of this problem was a new welfare benefit, Family Income Supplement, introduced in 1971, which was taxed and means tested, so that for every pound earned typically at least eighty-five pence, and sometimes more than the original £1, were debited in lost entitlements. ‘It is now a fact’, lamented Frank Field and David Piachaud in an article in the New Statesman that same year, ‘that for millions of low paid workers very substantial pay increases have the absurd effect of increasing only marginally their family’s new income and in some cases actually make the family worse off’.5 In this way the welfare benefits which had been the key element in originally enabling families to escape from poverty could now be seen as an element in the poverty trap itself – indeed, Field and Piachaud have a claim to have invented the term, although it is now often used, and we shall use it, in a much wider sense than their concept of a disease which the doctor unintentionally makes worse.6 Rather, our main concern in this book is to see what financial inclusion initiatives can do against persistent poverty in all its forms.

In addition to Beveridge’s five giants, two other key influences which contributed to keeping people in the poverty trap were social and financial exclusion. During the Conservative administration of Margaret Thatcher from 1979 to 1990 most indicators of income poverty rose, due to a sustained increase in unemployment (to a level of three million, or 12 per cent of the labour force, by 1986),7 a sustained reduction in the real value of welfare benefits and a change in the behaviour of banks – which in pursuit of their own viability closed a number of their branches in less remunerative, in other words poorer, neighbourhoods. Beyond this, banks typically refused to make loans to people who were unemployed or on benefits, and indeed often would not lend to anyone, employed or not, within defined postcodes.8 Thus, across large zones which often corresponded exactly to the council estates established by the first great flowering of the comprehensive welfare state in the 1940s and 1950s, those many low-income people who suffered from unmanageable levels of debt also found that little help in dealing with this predicament was available to them from conventional financial institutions. This is financial exclusion, and it links in an obvious way with social exclusion, which is the inability of poor people to participate in the social processes which determine people’s life chances (Askonas and Stewart 2000: 9, Lister 2004). The question which we now confront is: apart from the eroding welfare state, what alternatives were available within the private or voluntary (or public) sector to combat social and financial exclusion? The answer to this question will take us to the main theme of this book.

Two of the most significant alternatives available in principle to those caught in the poverty trap of the 1980s were mutual organisations (and especially credit unions) and sub-prime financial organisations (and especially home credit or ‘doorstep lending’ organisations). Both of these groups are an important part of the backdrop to the innovative financial institutions considered later in this book, and need some description here.

Credit unions are mutual financial organisations which lend and at the same time take savings deposits. They are legally obliged to define as members a group of people who share a ‘common bond’, often in the workplace or in the local community. They have existed since at least the eighteenth century, and during the century-and-a-half between the industrial revolution and the arrival of the Beveridge welfare state constituted an important part of the process by which working-class households built up a capital reserve to protect them against shocks9 and insure the household’s basic subsistence (Hollis and Sweetman 1998; King and Tomkins 2003; Maltby 2009). Within credit unions, loans are made (at a legal maximum interest rate of 12 per cent, raised to 24 per cent in only to those who have previously accumulated collateral in the form of savings, and this requirement excludes many people, since the poorest often see themselves as unable to save on a regular basis.10 Traditionally the role of credit unions has been seen as supporting household consumption and savings, and increasingly they are now used for acquisition of consumer durables, but they rarely lend for small business development. A more detailed discussion of credit unions, and a mapping of their role within our case-study areas, is given in Chapter 3.

Sub-prime financial organisations are, formally, those financial organisations not licensed by the Financial Services Authority to operate as banks, and therefore forced to raise resources from higher-cost sources than prime-rated financial markets. Often sub-prime financial organisations are willing to lend to riskier clients than high-street banks, and in particular to uncollateralised low-income individuals. A detailed account of sub-prime financial organisations has been provided by, amongst others, Kempson and Whyley (1999), Brooker and Whyley (2005), Collard and Kempson (2005) and several contributions to the Financial Inclusion Task Force, such as Finney and Kempson (2009) and Experian (2009). Sub-prime financial organisations, like credit unions, offer short-term loans for the purchase of consumer goods, but unlike credit unions do not ask for savings or any other form of security; in many ways, as we shall see, they substitute by intensive loan collection methods, just like microfinance institutions in developing countries, for the building-up of savings capacity amongst the poor. In some cases — such as pawnbrokers, who offer loans secured against jewellery or other collateral – these institutions have been established since pre-industrial times. Also existing since time immemorial and still thriving are loan sharks– unlicensed individuals offering unsecured loans at extremely high rates of interest to insecure people such as refugees and asylum seekers, who use violence and threats of it to enforce repayment.11 However, the most interesting category of sub-prime lenders is neither of these, but a group of legitimate and highly profitable commercial companies which have adapted themselves to the predicament of low-income borrowers by collecting loan repayments from borrowers not in the lender’s office, but in the borrower’s own house. These home credit companies, informally known as ‘doorstep lenders’ and also known as licensed moneylenders and weekly collected credit companies, are an oligopoly: the largest of them, National Provident, has over two million customers, and has almost half the market to itself, with three other companies, Cattles, London and Scottish Bank and S & U, accounting for another 20 per cent.12 Benefiting from their extremely strong bargaining position vis-a-vis poor clients and not being able to take collateral from them, they charge interest rates which amply reflect the risks of non-repayment and the costs of going to the doorstep to pick repayments up, and usually run well into three figures.13 Annual percentage rates on doorstep loans can be anywhere between 100 and 500 per cent (Kempson and Whyley 1999), though Palmer and Conaty (2002) cite examples where people were paying more than 1,000 per cent interest; the cost of credit emerging from our own surveys ( Chapter 4) averages out across our survey cities at around 190 per cent. These loans often include hidden charges, insurance premiums and the like, which are not necessarily obvious, especially to those with low levels of financial literacy. On the evidence of our interviews, most of these loans are used for covering the costs of everyday living and basic essentials (Palmer and Conaty 2002), rather than for luxury items.

The appeal of such massively expensive credit is, simply, uniqueness within the areas where it is supplied, compounded by ignorance about the cost and considerable skill in sales and client management on the part of loan collectors. The initial approach, in the Stocksbridge area north of Sheffield, typically comes in the form of a £50 voucher slipped through the door or available in the supermarket, which is then paid back in thirty-two instalments at £2.50 per week – an annual percentage rate of 399 per cent. This is the only form of credit seen to be available by those living on benefits – certainly to buy consumer durables, but sometimes even to pay for food. As illustrated by the following anecdote from the Meadowell estate in Newcastle, if you are living on benefits and most of your income is already pre-empted by debt repayments, your time horizons are extremely short:

Pat, who had worked in a hospital before having children, was struggling to make income support stretch to cover her food, fuel bills and nappies. Before she had paid off her first loan [from National Provident],14 a salesman from another credit company, Shopacheck, came to the door offering more vouchers. She took them and another loan to help clear the first. ‘I knew I was getting into debt but I needed it for the kids, just to survive that day.’15

Often the pressure to borrow, to the point of stealing, to afford the loan repayments comes through peer pressure via the children. As another Newcastle client mentioned,

I’ve had Provys [loans from National Provident] in the past and got so desperate I’d break into the meter on the TV to steal the money. You want your kids to be equal otherwise they’ll be targets. The kids say, ‘You’ve got snide trainers, you’re a tramp.’16

In spite of the high rates of interest which they charge, doorstep lenders and their agents are seen as sympathetic partners by many of their clients who are unaware of the cost which they are paying for credit, who are unaware of any alternative methods of getting credit, and who appreciate the time their collectors are willing to put into chatting to them about their problems and, indeed, postponing instalments without additional charge in the event of financial misfortunes encountered by the client (Brooker and Whyley 2005: Leyshon et al. If default or delay on repayment occurs on such a loan, then so far from being met with harassment it is courteously and helpfully rescheduled: the opportunity to extend the term of the loan is welcomed by doorstep lenders as a means of widening the market, and indeed is part of the process by which they are kept within the poverty trap. An enormous extension of the coverage of doorstep lenders occurred during the 1980s recession, and has occurred again during the current (2007–11) global crisis.

Against this background, let us pick up the story of poverty through the 1990s, and what resources and institutions were available to defend against it. Figure 1.1 provides a summary statistical picture of the time-pattern of headcount poverty, measured as half of mean income and separately assessed for different groups of households (working single people, working couples and pensioners, with and without children, and pensioners) from 1960 right through to the present.

Figure 1.1 Poverty in the UK: share of the population with below half average income, 1960–2009.

As Figure 1.1 shows, total poverty in the sense of those below half median income17 began to rise in 1977, well before the onset of the recession and the advent of a Conservative administration in 1979–80, and after a pause in the early 1980s it rose continuously until by 1992 it stood at 19 per cent of the population, or about two-and-a-half times its 1977 level, and, as best we can make the comparison, far above the proportion of the population calculated by Rowntree in York to be poor at the beginning of the 1950s.18 The real value of welfare benefits, as measured by the level of poverty among pensioners, also worsened sharply, from about 3 per cent to 7 per cent of the population over the same period. Many of those hurt in this way were the long-term poor and their dependants, initially made unemployed by the sharp cuts in declining industries such as steel, coal, textiles and heavy engineering in the 1980s and not able to shift into alternative jobs. Focussing on the financial dimension of their poverty, about one-tenth of the population, most of whom were poor, had no bank account and no means of borrowing. Credit unions in principle offered some relief for this predicament, but only a minor one because the poorest could not satisfy the requirement to save, and informal lenders also provided ‘relief’, but only in the superficial sense that they enabled the f...