![]()

1

Cuba: Providing the Model for a

Post-Petroleum Food System?

Petroleum-based food systems and food security

Over the next few decades, nations will be experiencing fluctuations and increasing scarcity of fossil fuel supplies, and this will affect food prices. Alternative farming and food systems are required. Industrialized countries in particular have been over-consuming fossil fuels by two-thirds, and their agricultural sectors have contributed this with their heavy dependence on cheap fossil energy for mechanization and as a basis for agrochemical inputs such as pesticides and fertilizers. The corresponding industrial food systems in which these farming systems are embedded are similarly dependent on cheap fossil fuels for the ever-increasing processing and movement of foodstuffs. The low fuel prices, combined with the industry's avoidance of paying clean-up costs of environmental pollution, have enabled the maintenance of low food prices (Vandermeer et al, 1993; Odum, 1994; Tansey and Worsley, 1995; Desai and Riddlestone, 2002; Harrison, 2004). Alternative, organic agriculture shows to perform better on a per hectare scale with respect to both direct energy consumption (fuel and oil) and indirect consumption (synthetic fertilizers and pesticides) (Scialabba and Hattam, 2002; Ziesemer, 2008). Many of the products of organic farming are processed and marketed through the industrial food system, but their prices are higher owing to their factoring-in of their impacts on the environment (Pretty et al, 2000). Although research has long been under way into energy alternatives, the agriculture and food sectors make little advance in developing alternative systems as long as fuel prices remain low.

A far cry from these petroleum-dependent populations are the 90 per cent of the world's farmers who manage 75 per cent of global agricultural lands and who have little recourse to fossil fuels and inputs (Conway, 1997). For many of these farmers, their low-input and organic status is by default rather than choice. Yet others have opted out of the opportunity to embrace industrialized, Green Revolution agriculture when offered to them.1 Should these farmers, and the food systems of their countries, be encouraged to take the industrialized route and to also depend on fossil fuels, or might they leap-frog into developing more efficient and effective alternative food systems?

Yet more localized, petroleum-free farming approaches are perceived by many as unable to deliver the yields required to feed growing populations, especially those of agrarian-based countries. An estimated 200 million people are classified as undernourished in Africa alone, and with forecasts predicting a shortfall in meeting the Millennium Development Goal of halving global food insecurity by 2015, pressure remains on the agricultural sector to increase yields (FAO, 1998; IAC, 2003; Benson, 2004). Evidence is mounting that alternative farming approaches can outperform industrialized farming in many circumstances (e.g. Pretty, 1998; Parrott and Marsden, 2002; Scialabba and Hattam, 2002; IFAD, 2003). However, this evidence is piecemeal and small-scale. No single country has made a policy commitment to, and effected, a nationwide sustainable, organic production approach. Thus there is no example of what a post-petroleum food system might look like, nor how to put this into place in terms of research, extension and policy support (Röling and Jiggins, 1998).

Cuba: the global example of a post-petroleum food system?

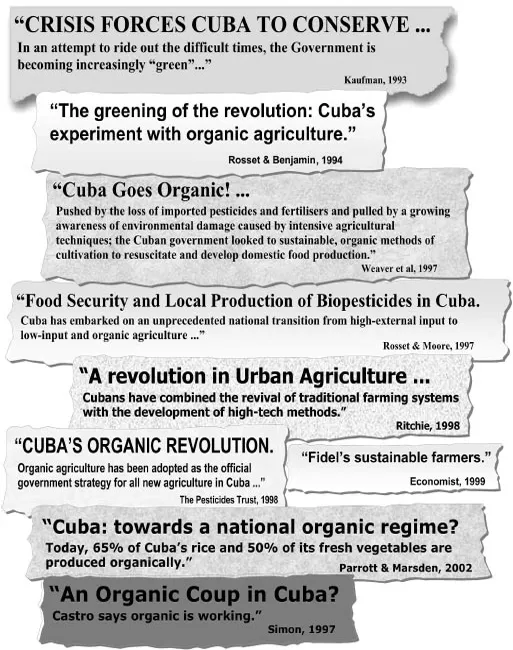

Or is there? Throughout the 1990s, reports were coming through on the resounding success of Cuba in heading-off a major national food crisis, a crisis that had been brought on by drastic shortfalls in imported fuel, food and agrochemical input supplies (these reports include, for example, Levins, 1990; Altieri, 1993; Carney, 1993; Rosset and Benjamin, 1994; Wilson and Harris, 1996; Rosset and Moore, 1997; Ritchie, 1998; Bourque, 1999; Moskow, 1999; Murphy, 1999). Figure 1.1 lists some of the headlines of these reports which emerged mainly through study tours2 and visits to Cuba by foreign interest groups. Was Cuba demonstrating a post-petroleum food system, feeding its people through state-supported, localized, organic farming?

The Cuban food system in crisis

Ever since its Socialist Revolution of 1959, Cuba has maintained restricted and selective contact with non-socialist countries. From an international perspective, this has resulted in a relative dearth of knowledge on all aspects of Cuban life, and a heavy reliance on anecdotal evidence. Nevertheless, there was no doubt that the dissolution of the Socialist Bloc of the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe in 1989 had brought an abrupt end to the support it had provided Cuba, and with this went the inputs that Cuba had relied upon to maintain its highly industrialized system of agriculture – petrol, machinery, chemical fertilizers and pesticides.

Figure 1.1 International reporting on the transformation towards organic agriculture in Cuba in the 1990s

From the beginning of the Revolution, Cuba had been influenced by the ideology of industrialization, in order to emancipate the rural population from the perceived drudgery of hand labour and to provide an abundant supply of cheap food. In the words of the Communist Manifesto, this was undertaken through ‘a triumphant conquering and domination of nature by man’. Cuba and the other socialist countries in the Council of Mutual Economic Assistance (CMEA) had relied on each other for obtaining whatever goods and services they required, this being necessitated by the trade sanctions of politically opposed countries. Cuba had then followed a model of externally assisted agricultural modernization, one with a far more rapid rate and spread than of other agrarian-dependent countries. This industrial growth was dependent on imported inputs and capital goods (Pastor, 1992). Cuba, a country without significant petroleum reserves, was in receipt of subsidized imports of fuel, agrochemical inputs, technology, training, many basic foodstuffs and medicines. In return it sold its tropical produce – largely sugarcane but also tobacco and fruits (along with other resources such as nickel) – to those temperate-climate socialist countries at more than double the world market price. This symbiotic trading relationship lasted for three decades, from the 1960s to the 1980s,3 and endured so well that the materially abundant decade of the 1980s was subsequently referred to in Cuba as ‘the years of the fat cow’.4

The abrupt changes of 1989 hit the Cuban agricultural sector particularly hard for four reasons. Firstly, Cuba had an extreme industrialized agricultural system, one that was using more tractors and applying more nitrogen fertilizer per hectare (192kg/ha) than similar production systems in the USA (Hamilton,2003). Mechanized irrigation systems covered over one-quarter of all crop land. Secondly, Cuba was importing not just a select few of the inputs and foodstuffs it required for survival but the large majority of them. In 1988, for example, 90 per cent of fertilizers and pesticides, and 57 per cent of food needs, were being imported (Rosset and Benjamin, 1993). Within the country, farms controlled by the Cuban Ministry of Agriculture, which worked 70 per cent of agricultural lands, were producing just 28 per cent of nationally consumed calories. Thirdly, not only did Cuba lose its Soviet trading partners, who were paying preferential prices for its products – an average of 5.4 times the world market price for sugar, for example – but just as Cuba was forced to enter the global sugar market, international commodity prices plummeted.5 Finally, over the previous 30 years Cuba had developed very little in the way of its own diversified agricultural products or light industry, either for export or for domestic consumption (Pastor, 1992).

The years of the fat cow were over. Between 1990 and 1993, according to reports, the availability of pesticides and fertilizers fell around 80 per cent, while fossil fuel supply dropped by 47 per cent for diesel and 75 per cent for petrol. Electricity levels also then fell, by 45 per cent. Agricultural production and food availability dropped to critical levels, with average calorific intake falling by as much as 30 per cent compared to previously and food imports dropping by over 50 per cent (PNAN, 1994; Rosset and Moore, 1997; Rosset, 2000).

The reported response to the crisis

In 1990, the state declared the start of a ‘Special Period in Peace Time’, a selfimposed state of emergency which urged the need for sacrifices in living standards, including an acceptance of insufficient food supplies, in order to buy the country time to build up its levels of self-sufficiency and particularly to meet basic food requirements (Rosset and Moore, 1997).6 Within this framework, the agricultural sector was tasked with finding solutions to production problems, and to do so using local resources. Given the importance that the Revolution placed on science and technology, this food security mandate was spearheaded by the scientific community.7 Researchers who had previously been beavering away in isolation on the development of alternative technologies were now mobilized and brought into the mainstream, and already-existing plans to produce organic pesticide and fertilizer products were put into operation and scaled-up in order to replace the shortfall of imported chemical inputs. In place of tractors, traditional teams of oxen were reinstated, and the knowledge and skills of older farmers were sought for the handling of the livestock as well as for other issues.

One major chronicler of this period, Rosset (2000, p206), had the following to say about the change in agricultural technologies:

In response to the crisis, the Cuban government launched a national effort to convert the nation's agricultural sector from high input agriculture to low input, self-reliant farming practices on an unprecedented scale. Because of the drastically reduced availability of chemical inputs, the state hurried to replace them with locally produced, and in most cases biological, substitutes. This has meant bio–pesticides (microbial products) and natural enemies to combat insect pests, resistant plant varieties, crop rotations and microbial antagonists to combat plant pathogens, and better rotations and cover cropping to suppress weeds. Synthetic fertilizers have been replaced by bio–fertilizers, earthworms, compost, other organic fertilizers, natural rock phosphate, animal and green manures, and the integration of grazing animals. In place of tractors, for which fuel, tyres and spare parts were largely unavailable, there has been a sweeping return to animal traction.

The area of change that gained the most international coverage and interest was that of urban agriculture (Weaver, 1997; Murphy, 1999). As the disastrous impacts of the import shortages grew more visible, the state decreed that all fallow and unused urban land be cultivated in perpetuity (en usufructo) and free from taxes. People from all professions took up this opportunity and, supported by the state, developed an intensive network of cultivated plots. By 1998, Havana had more than 26,000 urban gardens, producing 540,000 tons of fresh fruits and vegetables (Moskow, 1999).

For agriculture as a whole, yields of many basic food items increased, in some crops to levels higher than those of the previous decade, especially those of roots, tubers and fresh vegetables (Rosset, 1998; Funes, 2002). The food crisis had, according to reports, been lessened or even overcome. As Rosset (1996, p66) explains: ‘Although no figures are available, numerous interviews and personal observations indicate that by mid-1995 the vast majority of Cubans no longer faced drastic reductions of their basic food supply. ’

It was not only agricultural production that had apparently been trans-formed. According to reports, the Cuban government had succeeded in maintaining its socialist policy of feeding its people. Cuba had historically placed high priority on social concerns and had invested in the development and provision of education, communication channels, housing and health care facilities. It was this solid foundation that provided the bedrock for Cuba's survival (Rosset and Moore, 1997). Just over mid-way through the decade, Fidel Castro announced (1996): ‘We can proudly say that despite the difficult circumstances, we were...