![]()

Part I

Impacts, strategies and choices

The resource extraction industry and the economic and social status of indigenous and local peoples

![]()

Chapter 1

The resource curse compared

Australian Aboriginal participation in the resource extraction industry and distribution of impacts1

Marcia Langton and Odette Mazel

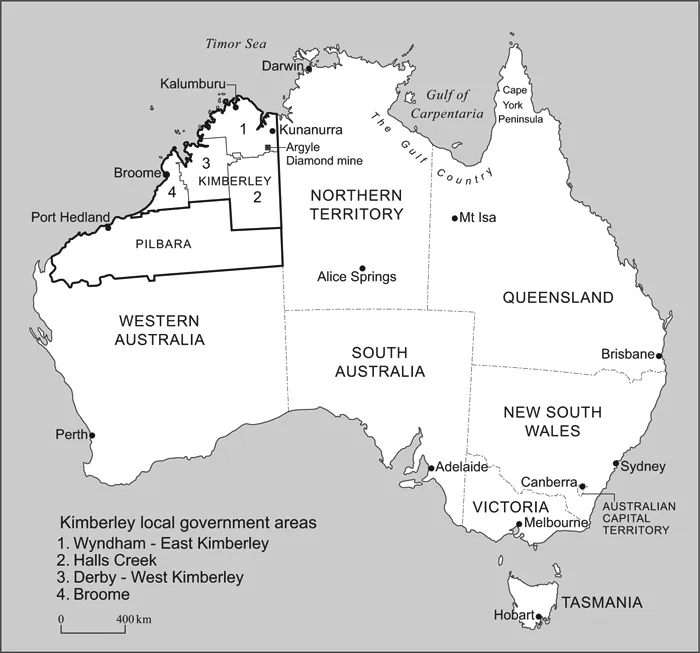

Figure 1.1 Australia showing mining areas and towns mentioned in Chapters 1, 2, 3 and 13

Introduction

The phrases ‘the resource curse’ and ‘the paradox of plenty’, as used by Auty (1993) and others, refer to the social and economic phenomenon in which many countries that are otherwise rich in natural resources experience poor economic growth, conflict and declining standards of democracy. In Australia, while the nation as a whole may not endure the failings associated with countries caught up by the resource curse, there are mining regions where conditions bear a remarkable similarity to those in countries described by Auty (1993), Sachs and Warner (1995), and others (see, for example, Mehlum et al. 2006). Sachs and Warner, for instance, have documented a ‘statistically significant, inverse, and robust association between natural resource intensity and growth over the past 20 years’ (1995: 21). There are some mining regions of Australia, where Aboriginal populations are significant majorities, for which the socioeconomic data show extreme poverty. The similarities of these populations with those discussed in the resource curse literature are so striking as to raise the question whether the ‘resource curse’ thesis applies to these Australian situations. In this chapter we explore this problem, highlight the lessons learned from research on the resource curse and discuss how they apply to Australia’s institutional and policy environment. We draw on research conducted on the negotiation and implementation of agreements with indigenous Australians, many of which are enabled by the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) (NTA). Such agreements, together with the mining industry’s approach to corporate social responsibility, are intended to ameliorate the disadvantages faced by indigenous communities. Despite these developments, however, little socioeconomic improvement has been achieved in these communities, and we look to explanations such as the inequitable distribution of resource project impacts on local peoples, issues of rent seeking and substitution and the potential effects of low levels of economic diversification to account for this phenomenon (see Switzer 2001). Finally, we discuss institutional and other reforms that might be effective in these circumstances.

The resource curse

The resource curse thesis correlates natural resource abundance to evidence of slow or declining economic growth, such that ‘resource-poor countries often vastly outperform resource-rich economies’ (Sachs and Warner 1995: 2; see also Auty 1993; Auty and Mikesell 1998). There are many hypotheses about the causes of this correlation, with the two most significant being economic and institutional (or political economy) factors (Sandbu 2006: 1155). In the first instance, resource booms tend to induce rising currency exchange rates, making export activities other than minerals and oil less competitive, and increasing the competitiveness of imports. This economic distortion (referred to as ‘Dutch disease’ after the negative effect of the natural gas revenues from the North Sea on Dutch manufacturers) also has a detrimental impact on non-mining sectors such as agriculture and manufacturing by bringing about increased wages and a loss of skilled labour (Sandbu 2006: 1155). Although this microeconomic factor has little direct application to the situation of Aboriginal Australians, some mining projects illustrate a similar trend, where the influx of highly paid labour causes localized inflationary effects, such as rising food and housing costs.

Explanations of the resource curse point to the mismanagement of the economic boom and identify ‘policy failure as the prime cause of the underperformance of the resource abundant countries’ (Lal and Myint 1996, as cited in Robinson et al. 2006: 448). Such underperformance might include greater ‘rent-seeking behavior by individuals, sectors or interest groups, and the general weakening of state institutions, with less emphasis on accountable and transparent systems of governance’ (Ballard and Banks 2003: 295; see also Ross 1999). For example, Robinson et al. (2006: 448) look to the critical importance of institutions in a resource boom, since ‘these determine the extent to which political incentives map into policy outcomes’. They suggest that competent institutions with strong accountability mechanisms will avoid the ‘perverse political incentives that such booms create’ (Robinson et al. 2006: 447). Meanwhile, Mehlum et al. (2006:1) also point to the particular importance of institutional arrangements for distributing resource rents. Relying on the distinctive analysis of economist Amartya Sen, Stiglitz (2006) concurs with such explanations, arguing that poor distribution of resource-derived wealth is the cause of poor socioeconomic activity in mineral-rich areas. He proposes a number of solutions: partnering institutional quality and improved governance with sustainable wealth management, prioritizing transparent and accountable institutions to reduce the scope for corruption, and improving conditions for investment (Stiglitz 2006; see also Sen 1999).

It is these findings which drew our attention to some similarities with the impacts of the resource curse among Australian Aboriginal populations affected by mining operations, although we also note that there are significant differences to consider. For instance, the resource curse thesis is usually applied to national economies rather than regions within nations. However, even though Australia is an accountable and competent state, there is potential for this conceptual framework to lead us to a better understanding of the conditions faced by Australian Aboriginal communities in resource-rich settings and in particular, how these communities might be able to benefit from the expansion of the minerals economy.

Mining in the Aboriginal domain: legal frameworks and corporate responsibility

Mining activity in Australia is currently undergoing its largest escalation in history, led by operations in Western Australia’s Pilbara region (Taylor and Scambary 2005). With more than 60 per cent of these mineral operations lying in the vicinity of Aboriginal communities (Department of Industry, Tourism and Resources 2007: 3), the need to ensure that sustainable benefits accrue to these populations has emerged as an important issue.

While in Australia the history of conflict observed in many resource curse economies has not occurred on a similar scale, mutual antagonism between the mining industry and indigenous communities in the 1970s did create tensions that spilled over into national politics, leading to extensive litigation by indigenous people (Hawke and Gallagher 1989; Switzer 2001: 10–11). The introduction of legal frameworks enabling the participation of indigenous communities in mining negotiations, along with political pressure and international developments regarding corporate social responsibility, dramatically changed this state of affairs (see Crooke, Harvey and Langton 2006; Harvey 2004; Langton et al. 2004).

Formal recognition of indigenous rights encouraged the minerals industry to take a new approach, acknowledging the detrimental impacts of mining on Aboriginal communities and their entitlement to benefits as a result. Mining companies became increasingly aware of the importance of establishing cooperative working relationships with local indigenous people, and recognized that the negotiation of sustainable relationships was preferable to costly litigation and ensuing delays to exploration and mining (Lenegan 2005; World Business Council 2000). One important aspect of mining companies’ need to gain security of access to resources is the concept of ‘social licence to operate’ – which requires commitment to mining operations by Aboriginal and local communities, as well as an agreement on conditions for access to, and use of, the land (Department of Industry, Tourism and Resources 2007). The social licence to operate obtained by making agreements with affected indigenous groups goes far beyond the standard notion of corporate social responsibility, particularly because agreement on the part of indigenous parties consenting to mining operations usually goes hand in hand with specific benefits aimed at improving their economic and social outcomes. Corporate social responsibility practices, on the other hand, are not directed specifically at affected groups, and are instead aimed more generally at a company’s reputational standing as a corporate citizen, frequently supporting environmental and carbon reduction projects of global significance.

In Australia’s federal system of government, Commonwealth, state and territory legislation applies to a range of land access matters, and also to dealings with indigenous people. Natural resources are legally owned by the federal, state or territory governments, which do not engage in commercial mineral exploration and development, but rely on the private sector to undertake these activities. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples currently hold more than 20 per cent of Australia’s land mass under statutory titles (for example, under the Aboriginal Land Rights (Northern Territory) Act 1976 (Cth)); however, since the High Court’s ruling in Mabo v Queensland (No. 2) (1992) 1 CLR 175 (Mabo), other areas, such as unallocated Crown land, may be subject to native title rights or native title applications.

While various statutory land rights schemes provide some rights for indigenous peoples in particular parts of Australia, native title legislation applies nationally and provides an important impetus for government and industry to engage with indigenous people. Following the Mabo case, the Commonwealth government passed the NTA to provide a legislative framework for the recognition and protection of native title, and establish procedures that would allow native title claims to proceed (see NTA: section 4). Importantly, the NTA provided a set of procedural rights relating to ‘future acts’, which could include any dealings in land that might affect native title – such as the development of natural resources (see Bartlett 2000; Stephenson 2002). In some instances, the NTA provides registered native title holders with the right to be notified and consulted about a proposed action, and the right to object and be heard by an independent body. The NTA was amended in 1998, when Indigenous Land Use Agreements (ILUAs) were introduced as another means of validating future acts through negotiation. ILUAs have become an increasingly important way by which mining companies and others engage with local communities, often achieving the social and legal conditions for long-term, sustainable mining operations (Godden and Dorsett 1999). These agreements offer a flexible approach to managing a range of issues, including access to land, resources and infrastructure, environmental management, tourism, cultural heritage, compensation and employment and training opportunities (Langton and Palmer 2003; Tehan et al. 2006). They also provide non-indigenous parties with legal certainty, because once the agreements are registered with the National Native Title Tribunal, they become binding on all those who hold native title into the future.

The recognition of native title and the development of instruments, standards and statutory rights have provided a relatively sound governance and administrative system for native title rights and access conditions for mining, energy and exploration projects. There are, however, several limitations to good practice in the native title legal framework. Of utmost concern is the urgent need for capacity building to ensure a stable administrative environment and institutional arrangements – an issue that will be discussed later in this chapter. As a consequence of the introduction of agreement-making provisions into the NTA, there has been a significant increase in the number of agreements made with indigenous parties. There are now 554 ILUAs registered in Australia, and over 3,000 future act determinations (National Native Title Tribunal 2012).

While the mining industry’s emphasis on resolving native title issues by negotiation and its growing awareness of corporate social responsibility have resulted in settlements with substantial financial, employment and other benefits for indigenous groups, the economic status of indigenous communities is falling well behind the rest of Australia (Taylor and Scambary 2005). Native title groups have obtained a range of direct benefits from engaging with mining companies; these benefits, in the form of financial payments, employment initiatives and contract opportunities, are primarily included in negotiated agreements. However, the mere act of concluding agreements has not necessarily assured meaningful or equitable outcomes for a significant proportion of indigenous communities (O’Faircheallaigh 1995, 2003, 2004; see also Langton and Palmer 2003; Taylor and Scambary 2005).

While providing some opportunities, the current legislative and policy framework has its limitations. The lack of government investment in services, facilities and infrastructure in the rural and remote mining provinces and the declining economic status of Aboriginal people are becoming increasingly evident, drawing our attention to the correlation between these developments, as well as the potential relevance of the resource curse thesis and the issues of institutional capacity and other measures referred to in the literature.

Case study: the Pilbara region

In the Pilbara region, Aboriginal people became artisanal miners after World War Two (Holcombe 2006), living on the margins of the large-scale mining operations which commenced in the 1960s. In this region, there are more than 10 agreements with local indigenous grou...