- 270 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First published in 1985, this study is a comparative examination of industrialisation and industrial policy from the early 1960s to the early 1980s in the five original member countries of the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN): namely Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand.

The work provides an integrated overview of industrial policies and performance in the five countries and forms essential reading for both those with a specialist interest in the ASEAN countries and their economic performance, and for students of industrialisation in developing countries the world over.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Subtopic

Entwicklungsökonomie1 Introduction

THE last quarter century has witnessed a major relocation of economic activity towards the East Asian region. Japan, the three Northeast Asian NICs (newly industrialising countries) Hong Kong, South Korea and Taiwan, and the five original ASEAN member countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, and Thailand) have generally recorded very rapid rates of economic growth, both in comparison with other regions and, within the region, with earlier periods, especially prior to 1940. Consequently, these countries’ share of world production and, particularly, world trade has risen very significantly. For much of this period, and for most countries, manufacturing has been the fastest growing sector of the economy. One of the stylised facts of economic development is an increasing share of manufacturing in gross domestic product (GDP). In the case of this region, manufacturing has been given an additional impetus by the strong growth of manufactured exports.

This book examines the industrialisation of the five original ASEAN member countries from the 1960s to the early 1980s. Its sub-title might have been a ‘case study of trade and industry in five developing countries’. Our aim is to investigate industrial performance and policies over these two decades. This period has witnessed the transformation of industry in the region. All five countries, with the partial exception of Indonesia, have developed a fairly sophisticated and modern manufacturing sector although, of course, much industrial activity is still located in small-scale and cottage enterprises.1 Our intention is to analyse the growth and changing structure of manufacturing production and trade in the five countries, and the underlying policy issues and responses. The policy dimensions of our analysis are critical. Important policy changes have been central to the region’s economic and industrial growth, and especially the increased emphasis on exports. An understanding of the factors accounting for these policy changes is therefore very important.

Around 1960, manufacturing activities in the five countries consisted overwhelmingly of resource-based processing and the production—or more often assembly—of simple consumer goods. Manufactured exports were generally minimal. The Philippines and Singapore were partial exceptions to these generalisations. The Philippines commenced the push for industrialisation in the late 1940s, shortly after full independence in 1946, and well before most of its neighbours. Singapore had, historically, a strongly developed entrepot trade and services sector, in addition to its processing of raw materials from Indonesia and Malaysia. But, with these two relatively unimportant exceptions, industrialisation in the region had barely begun.

The first systematic attempts to promote industrialisation got under way at about this time; in the Philippines somewhat earlier than the rest; in Indonesia a good deal later. The factors explaining the increased emphasis on industrialisation in the first place need not be recounted in any detail here. Industrialisation was occurring in any case as per capita incomes rose. But three factors which motivated governments to hasten the process may be noted briefly. One was the belief that future international market prospects for primary products—which dominated the region’s exports—were poor. The 1950s witnessed a sharp decline in commodity prices, after the Korean War commodity boom of 1950–51. The decline over such a short period in no way constituted empirical support for the deteriorating terms of trade thesis, then in vogue, but it did influence policy makers. A related consideration was the desire to diversify the structure of exports and reduce the heavy reliance on a few commodities. Two other interrelated factors contributed to the drive for industrialisation. The first was the belief, articulated strongly by nationalist groups, that the colonial power had distorted the country’s economic structure. According to this view, economic development in the colonial era was ‘lopsided’, placing undue emphasis on the agriculture sector and, in particular, cash crop exports. Industrial promotion was therefore seen as a means of redressing this imbalance. A related argument was based on the perceived association between industrialisation and economic power. The high income, developed countries possessed large industrial sectors. Industrialisation was thus seen as the road to economic development.

The intensity, duration and mechanics of industrial promotion policies varied considerably in the region. All countries except Singapore initially saw import substitution as the path to industrialisation. Even Singapore experienced a very mild period of import substitution. The most sustained period of import substituting industrialisation occurred in the Philippines, which embarked on such a policy in the late 1940s. Measures to promote industry were often introduced in an ad hoc manner, not infrequently in response to a balance of payments crisis. Here also, the Philippines is a prominent example. As Power and Sicat (1971) observed, the introduction of foreign exchange and import controls was initially designed to resolve a payments crisis, but they subsequently became the cornerstone of industrial policy. The relative importance of tariff and non-tariff measures also varied considerably among the five countries. Whereas Singapore, especially, and Malaysia relied mainly on tariff protection, there was considerable resort to non-tariff measures in the other three countries. This is particularly so in Indonesia and the Philippines, where tariffs have never been the main instrument of protection (except for a few brief episodes during the late 1960s in Indonesia and the mid 1960s in the Philippines).

Import substitution policies generally resulted in a spurt of industrial growth, but they did not provide the basis for a sustained period of industrialisation. After the completion of the ‘easy phase’ of industrialisation, when manufactured output grew rapidly within the confines of the small protected domestic market, a period of market saturation quickly followed. Industrial growth was then restricted essentially to the growth of the domestic market. There was no automatic ‘spillover’ to the export market, as policy makers had originally anticipated. To simplify, the maintenance of continued rapid industrial growth—in Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand around 1970 and in Indonesia about 1980—required either the vigorous promotion of exports or a secondary round of import substitution in more capital- and skill-intensive activities.

Policy makers generally responded with a mix of policies combining elements of both options, but with primary emphasis on the former. What factors accounted for the policy reorientation? The first and most important was disappointment with the results of the import substitution strategy. Expanded manufacturing output did not translate into increased exports. The newly established manufacturing sectors were frequently not internationally competitive, often because of the nature of policy measures in the import substitution phase.

Several other factors accounted for the policy transformations and the increased emphasis on exports. For one thing, the ‘demonstration effect’ of the extremely rapid export growth of the Northeast Asian NICs (and Singapore) was important. These countries’ experience of export-led growth was a powerful antidote to the view in several ASEAN countries (and elsewhere) that developing countries had little prospect of penetrating the international market for manufactures. The export growth of these countries—and, potentially, of ASEAN—was facilitated by the rapid growth of the international economy and by an increasingly liberal trading environment in the 1960s and early 1970s. In an era of rapid growth, structural changes necessitated by growing developing country exports were more easily accommodated

A third factor was the changing climate of intellectual opinion. If the 1950s was characterised by ‘export pessimism’ and resulting inward-looking policies, mounting empirical evidence and theoretical work in the 1960s and 1970s provided the intellectual justification and—through the activities of some international development agencies—financial inducement for policy change. A fourth factor was changes in production and design technology which facilitated the physical separation of production processes. The labour-intensive stages of many products have moved ‘offshore’ from the developed countries to new low-cost production centres, under the umbrella of international subcontracting networks. Some of these activities have been important elements of the ASEAN export drive. A final factor, of particular relevance to Indonesia since 1981, has been the slump in commodity prices (most notably of petroleum), and the consequent incentive to develop new export products.

Government intervention in the policy re-orientation has been of major importance. Governments in the region, Singapore’s included, have been highly interventionist. Government policy first induced the push for import substitution, and later the stress on export-oriented industrialisation. The effects of this intervention have varied considerably, in some cases overseeing a relatively smooth transition towards new goals, but in other cases inhibiting the necessary adjustments. But, while the economic effects of such interventions are reasonably well understood, the motives are much less so. In particular, the selection of policy instruments and considerable variations in the pattern of intra-industry intervention both require attention if the policy changes are to be properly understood.

It needs to be emphasised that, while ASEAN is an increasingly harmonious and effective regional organisation, there is no such thing as ‘the’ ASEAN experience with industrialisation. The five countries are an eclectic group with little else in common apart from proximity, a desire for regional co-operation and (generally) rapid economic growth. There is enormous variation in their per capita incomes (the highest, Singapore, is more than ten times greater than the lowest, Indonesia), resource endowment and trade and economic structures. Frequently, as we shall see, it is useful to see them as a spectrum, ranging from Singapore at one extreme and Indonesia at the other, with the remaining three countries adopting intermediate positions. The region’s diversity provides additional justification for an examination of its industrialisation experience which has lessons for a wide range of other developing countries.

Layout and organisation

We have structured the book around the twin themes of the changing comparative advantage of the ASEAN economies in general and industry in particular, and the political economy of government intervention in the ASEAN export drive. The book consists of three main sections.

Chapter 2 constitutes the first section, which presents an overview of ASEAN industrialisation. We first provide a historical background to the present policies, examining in some detail the transition from import-substituting to export-oriented industrialisation. Next follows a brief profile of ASEAN manufacturing industry. Although we are not concerned primarily with the relative merits of the two strategies (in our view this debate has been effectively settled) we do review some of the more important issues in the debate, with special reference to the ASEAN countries. Finally, we consider factors which will affect these countries’ future export prospects, and we draw attention to some of the more important policy issues in industrialisation.

In the second section, which consists of chapters 3 and 4, we examine the political economy of government intervention, focusing on protection and regulation. Both issues are important, since they may impede the effective exploitation of comparative advantage. In the case of protection, both ASEAN and developed countries’ policies are considered. Developed country protection will obviously affect the market penetration of developing countries, though the evidence through to 1980 suggests these effects have not been great. Protection in ASEAN has a similar effect, especially where the system of protection discriminates against potential export industries.

Government intervention in the form of industrial regulation—the subject of chapter 4—raises many similar issues. This is an issue which has received much less attention than protection, and it is not easily amenable to quantitative analysis. But its impact on industrial performance and export growth is equally great. In contrast to protection, which ranges from very little in Singapore to a great deal in Indonesia and the Philippines, all ASEAN governments regulate their economies extensively. The important distinction, however, is that regulation in some countries is ‘efficiency-promoting’, while in others it is ‘efficiency-retarding’.

The third section, chapters 5 and 6, investigates in some detail the changing patterns of manufacturing production and exports. The focus in chapter 5 is on structural change. We first examine these changes according to the usual indicators of structural change. To understand these developments more fully, we develop the theory of changing comparative advantage and devise a simple classification of manufacturing industries, and we analyse the changing pattern of production and trade in the light of our theoretical formulation. Chapter 6 extends our analysis further, focusing in particular on changing comparative advantage in and the performance of manufactured exports.

Finally, in chapter 7, we summarise our major conclusions and examine future prospects.

An analysis of changing patterns of production and exports for five countries over two decades, and an explanation of these changes, is inevitably a somewhat data-intensive operation. In revising the manuscript for final publication we discarded approximately half the tables prepared for the first draft. Many tables and figures have been retained because we believed they were essential for a full account of ASEAN industrialisation. Ultimately, we leave it to the reader to judge whether we have erred on the side of omission or commission. In passing, we should finally note that data limitations have in some cases precluded a more thorough examination of the issues, and in all cases the data should be interpreted carefully. Trade statistics are generally more reliable—if only because it is possible to check for accuracy with reference to trading partner statistics—and their collection is more comprehensive. Production statistics are generally less accurate and the coverage less complete, especially in the analysis of long-term trends.

2 The export drive: an overview

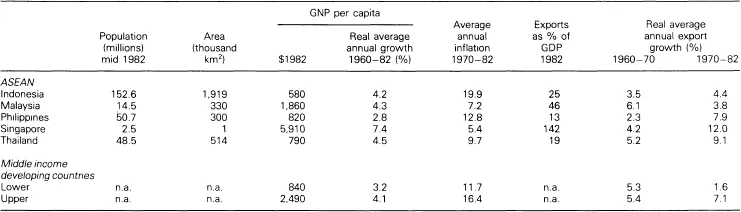

FIVE like-minded Southeast Asian nations, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand formed a loosely structured regional grouping called the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in 1967. Brunei became the sixth member of ASEAN on 7 January 1984, a week after it became an independent nation. ASEAN represents a group of market economies most of which have had a long tradition of looking outward. The economic size of ASEAN is considerable: in 1982 its population was 269 million, its GDP was about US$207 billion and its annual foreign trade flows exceeded US$141 billion. One important distinguishing feature of ASEAN has been the unusual dynamism of the member nations, whose production and exports have generally been growing at rates well above world averages since the late 1960s. Apart from the slower growing Philippine economy all five original members of ASEAN grew faster than ‘middle income’ (as defined by the World Bank) developing countries (Table 2.1). Another distinguishing feature of the regional grouping is the substantial intra-regional differences in terms of land area, population size, per capita income, and economic growth (Table 2.1).

The ASEAN economies have experienced significant structural changes in the last two decades (Table 2.2). There has been a continuous and substantial relative decline in agriculture, accompanied by a large increase in industry—more than doubling in the case of Indonesia and Singapore. The share of services has broadly remained constant, except for the decline in Singapore, reflecting the reduced relative importance of entrepot trade in its economy.

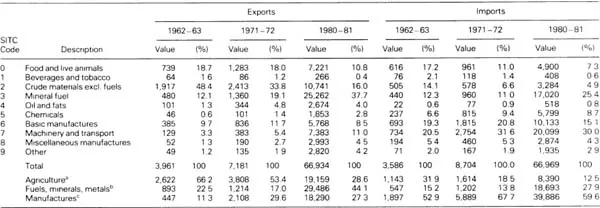

There have been important changes in the composition of aggregate ASEAN exports and imports since the early 1960s (Table 2.3).

With regard to exports, the main trends are a rapid decline in the relative importance of agriculture, and increased manufactured and fuel and minerals exports. The latter—mainly SITC 3—rose very sharply in the 1970s, in response to increased prices for Indonesian and Malaysian petroleum exports (Brunei is not included). This had the effect of reducing the share of manufactured exports, even though the absolute amount rose very rapidly. Within manufacturing, the share of machinery and transport equipment continued to increase, despite the greatly enlarged share of fuel and minerals. Consequently, whereas in 1962–63 the share of agricultural products was approximately six times that of manufactures, by the early 1980s they were similar. Nevertheless, ASEAN continues to be a net importer of manufactures, unlike the other two categories. In fact, the share of manufactures increased slightly over the entire period, in spite of greatly increased fuel imports for the region’s three net fuel importers. The promotion of manufactured exports has resulted in a larger absolute increase in manufactured imports compared with manufactured exports, although the latter’s growth has been far more rapid.

Table 2.1 Basic economic data: ASEAN and middle income developing countries

Notes. n.a. not available

Source: World Bank (annual)

Table 2.2 Production structure of ASEAN economies

Sources. World Bank (annual), and World Bank (1984)

Table 2.3 Commodity composition of ASEAN trade, 1960s to 1980sa (million $ or %)

Notes Figures refer to average for each pair of years.

a SITC 0, 1, 2, 4, excluding 27 & 28

b SITC 27, 28, 3, 68

c SITC 5–9 less 68

Source. Data Bank

Brunei, Indonesia and Malaysia enjoyed substantial trade surpluses throughout the 1970s, owing to buoyant prices of petroleum and other primary commodities. The surplus for the latter two countries was especially large in 1980 following the price increases of OPEC II (Table 2.4). The remaining three ASEAN countries have generally experienced trade deficits, which rose rapidly in the 1970s.

The subsequent decline in the real price of many commo...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Original Title Page

- Original Copyright Page

- Contents

- Tables

- Figures

- Abbreviations

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The export drive An overview

- 3 Protection and market penetration

- 4 Government regulation and industrialisation

- 5 Industrialisation and structural change

- 6 Manufactured exports Performance and shifts in comparative advantage

- 7 Conclusion and future prospects

- Appendix I A note on data sources and classifications

- Appendix II ISIC (production) classification of manufactures

- Appendix III SITC (trade) classification of manufactures

- Appendix IV A formal presentation of the constant market shares analysis

- Appendix V The extended commodity classification

- Notes

- References

- Index of Subjects

- Index of names

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Export-Oriented Industrialisation by Mohammed Ariff,Hal Hill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Volkswirtschaftslehre & Entwicklungsökonomie. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.