![]()

1 Godardville

Alphaville exists

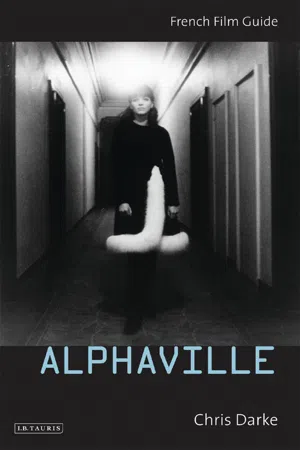

Alphaville, São Paulo, 2003 (photograph courtesy of Desperate Optimists)

Seven and a half miles from the heart of São Paulo there is a gated community that houses 30,000 of the city’s richest and most security-conscious residents, many of whom travel by helicopter to work among the 17 million other inhabitants of the world’s third largest city. According to The Washington Post, ‘At night, on “TV Alphaville”, residents can view their maids going home for the evening, when all exiting employees are patted down and searched in front of a live video feed.’1 In his account of ‘a walled city where the privileged live behind electrified fences patrolled by a private army of 1,100’, the Post’s correspondent failed to discover which keen ironist had named the development after the film by Jean-Luc Godard.2 Nor, I suppose, would it have been much appreciated had the reporter, as he flew low over the teeming favelas, the prisons and choked highways, casually asked his host, a CEO and Alphaville resident, ‘You do realise you’re living in a movie, don’t you?’

Developed by the Alphaville Urbanismo Corporation in the 1970s, Alphaville São Paulo ‘resembles its fictional namesake in elaborate and all-encompassing surveillance techniques’, writes an American professor of urban studies, ‘including high walls, hidden cameras and alarm systems … The Alphaville gym specialises in self-defence and is called CIA.’3 The facts about the development get better, or still worse, depending on whether one prefers dystopia to remain firmly in the realms of fiction or to come, fully-fledged, to life:

To advertise Alphaville, the company sponsored some episodes of a popular prime-time Brazilian soap opera whose leading male character is an architect. The architect and his mistress visit Alphaville where, according to Brazil’s Gazeta Mercantil, the characters exalt the safety, freedom and planning of the place, comparing it to the neighbourhoods shown in US films.4

And so … Godard’s film about a city of the future, shot on location in the Paris of the mid-1960s, has endowed not just one but 30 ‘gated communities’ in Brazil with its name.5 And reality, having provided fiction with the raw material for its most dystopian scenarios, returns the compliment by materialising them. The back and forth between image and reality is dizzying: from CCTV to soap opera, from European art cinema to aspirational Hollywood, and back again. Where does the utopian projection end and dystopian reality begin? We might call it, with a certain queasiness, the ‘Alphaville effect’. But surely this is only an accident of naming, a sick joke? Are the ‘Alphas’ paying to inhabit their top-security luxury lock-up only so-called compared to the favela-dwelling ‘Omegas’? How long before Alphaville becomes a suburb of Los Angeles, a satellite of Mumbai? As the oracular tones of the supercomputer Alpha 60 remind us at the beginning of Godard’s film, there are indeed times when ‘reality becomes too complex for oral transmission. But legend gives it a form by which it pervades the whole world.’ In the face of a reality too complex, too ironically dystopian, too straightforwardly ugly to address directly, let us attend to the legend.

Tarzan versus IBM

Legend has it that Alphaville almost didn’t exist. Interviewed in September 1964, Godard alluded to a forthcoming project: ‘I’ve a film to make in December with [Eddie] Constantine. I’ve no idea at all what I’m going to do.’6 The film producer André Michelin (a scion of the famous French tyre manufacturing family) had proposed to the director a film featuring Eddie Constantine, who had been a star of French cinema during the 1950s playing the FBI tough guy Lemmy Caution, and both director and star had agreed. However, one of the director’s options at the time was to drop, or at least delay, the project in favour of making a film in the United States. The project in question was Bonnie and Clyde, which François Truffaut had been interested in making but had to abandon when the financing came together for his own excursion into science fiction, an adaptation of Ray Bradbury’s 1953 novel Fahrenheit 451. In a letter to the scriptwriters, Robert Benton and David Newman, Truffaut mentioned that he had ‘taken the liberty of passing [the script] on to Jean-Luc Godard’.7 Godard met with the producers in November that year. ‘What it boiled down to was this,’ Benton and Newman recalled: ‘he had been supposed to start another film in Paris next month but he didn’t feel much like doing it. He liked the script of Bonnie and Clyde very much and thought he would do that. In three weeks from now.’8 The film Godard ‘didn’t feel much like doing’ was obviously the as yet untitled Eddie Constantine project, but let us stay with Benton and Newman’s recollection of that meeting for a moment, if only to entertain the wonderfully improbable idea of Godard in Hollywood.

Our producers went white. But, they said, we were not ready, that is, there was no deal, no financing, no studio. Godard said it didn’t matter; we immediately agreed with him. Why not? He said, that day, two things which are forever writ upon our memories: ‘If it happens in life, it can happen in a movie.’ This to the producer’s objection that the key elements might not be perfectly pulled together in three week’s time. And, ‘We can make this film anywhere; we can make it in Tokyo.’ This in response to the producer’s objection that weather conditions were not right in Texas for shooting at this time of year. A call to the weather bureau in Dallas was made. Strong possibilities of precipitation were predicted. ‘You see?’ said the producer. ‘I am speaking cinema and you are speaking meteorology,’ said Godard.9

Bonnie and Clyde as directed by Godard was not to be. Back in France, where his reputation was based at least in part on being the most extreme of the new wave innovators, Godard’s singular approach to filmmaking could also cause problems, and Alphaville was a case in point. Raoul Coutard, the director of photography on all but one of Godard’s 1960s films, remembers how, in order to get a film off the ground, the state film body, the Centre National de la Cinématographie (CNC), required not only a screenplay but a detailed shot breakdown known as a découpage:

It had to specify things like ‘wide shot’, ‘medium shot’, ‘close up’. Everything was very precise. So a production plan was made and signed by the filmmaker, the director of production and the cinematographer in order to show that the film could be made in the time allotted. But Jean-Luc didn’t work from a screenplay so he got his assistant to write one and the découpage was made from that. But it was a fake document.10

The problems arose because Alphaville was conceived as a Franco-German co-production. Godard’s assistant director on the film, Charles Bitsch, takes up the story:

Eddie Constantine was very popular in Germany and his films made money there, so German producers were always on the lookout to co-produce a film with the French starring Eddie Constantine. When I started to work on the preparation for the film there was no screenplay, which was often the case with Godard. I tried, without success, to get him to write three or four pages for me so that I could get to work. Michelin was also impatient for a screenplay which he needed to set up the co-production with his German partners. Finally, Godard asked me to write the screenplay. I asked him to put me on the right tracks and all I got by way of a response was that he lent me three novels by Peter Cheyney, who created the character of Lemmy Caution. He told me that I only had to read them and write a story in the same genre. So I wrote thirty pages, which Godard gave to Michelin as the screenplay. I kept quiet about who’d written the screenplay as it had landed in the hands of the Germans who signed a contract with Michelin on the strength of it and the film went into production. Of course, Godard didn’t use a single word of what I’d written and he was right not to. On the other hand, there were serious consequences for Michelin. When the Germans saw some of the rushes and discovered the scam they pulled out of the co-production and demanded to be reimbursed for the first payment made when the contract was signed.11

Nevertheless, by January 1965 Godard had begun shooting a project initially known as Tarzan versus IBM, which the director had described in a questionnaire published in Cahiers du cinéma the same month as ‘an experimental art-house adventure film’.12 The film was shot between January and February, and the finished work, now entitled Alphaville, une étrange aventure de Lemmy Caution, won the prize for Best Film at the Berlin Film Festival and was released in Paris on 5 May, where it played until August and attracted some 160,000 spectators. It’s worth considering the facts and figures behind this brief exposition. Five months from filming to release represents a speed of production that is unimaginable in filmmaking today and was exceptional then. Working quickly and cheaply, Godard turned out films at an astonishing rate throughout the 1960s. Alphaville was his ninth in the five years since his debut with À Bout de souffle in 1960, and in the same year as Alphaville he also made two others, Pierrot le fou and Masculin-Féminin. By 1968, the year in which he abandoned commercial cinema for a more politically radical form of filmmaking, Godard had made a total of 18 features and eight shorts.

Alphaville has the reputation of being something of an anomaly among Godard’s pre-1968 films. His sole feature-length foray into science fiction and one of his few encounters with a star with major box-office appeal, in this case Eddie Constantine (three years earlier Godard had worked with Brigitte Bardot in Le Mépris, which proved to be a box-office success in terms of Godard’s public, less so in terms of Bardot’s), it’s a film that has been strangely neglected by critics. According to Marc Cerisuelo, the author of a handy French monograph on the director, Alphaville is the most ‘explicitly “secondary” of his works’ and is described as such because of the presence of Eddie Constantine as Lemmy Caution, a stalwart of French thrillers of the 1950s derived from the novels by Peter Cheyney.13 Punching and shooting his way through Alphavill...