eBook - ePub

Advanced Typography

From Knowledge to Mastery

Richard Hunt

This is a test

Share book

- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Advanced Typography

From Knowledge to Mastery

Richard Hunt

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Once you have learnt the fundamentals of typography, there is still a wealth of knowledge to grasp to really become a master in the art and craft of working with type. In Advanced Typography, expert practitioner and instructor Richard Hunt goes beyond the basics to take your understanding and usage to the next level. Taking a practical approach, the book combines visual, linguistic, historical and psychological systems with the broad range of applications and audiences of type today. From the challenges of designing across media and cultures, to type as information and craft, Hunt marries theoretical context with applied examples so you feel confident in improving your skills as an advanced typographer.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Advanced Typography an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Advanced Typography by Richard Hunt in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Design & Typography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

We do not have to learn the techniques of the past, but we do have to learn how to manage and carry out aspects of typography that used to be delivered by professional typographic service providers. At the same time, there are freedoms and possibilities attached to type that were never possible before. Designers must be prepared to explore new and changing technological possibilities.

1

The invention of typography confirmed and extended the new visual stress of applied knowledge, providing the first uniformly repeatable “commodity,” the first assembly-line, and the first mass-production.

Marshall McLuhan, The Gutenberg Galaxy

Changing technologies and practice

There is no question that the way people read now is different than it was in the past. People’s attention spans are shorter, and there is far more to read, across a wider choice of media. Although this trend has been connected to the advent of the internet, it can be traced to the Industrial Revolution, when increased production efficiencies, marketing and the increase in wage-earners with some disposable income meant that more and more reading material became available to an increasingly literate public. Newspapers and illustrated magazines gave citizens more to read, leading to more competition for their attention. The amount of typographic material has exploded again with the internet, while the volume of printed type has diminished surprisingly little.

In a typical printed book, the reader’s experience is largely controlled. The text is linear and is unfolded page by page, and books are largely self-contained. Some books may refer to other books, sometimes in text, often in footnotes or endnotes, but in most cases, a book is still expected to be something that can be used without reference to other works. The reader’s expectation is for a book to be a complete experience. A table of contents and an index may give readers options in how they engage with parts of a book, but the basic reading structure is influenced and formed by the book’s structure. Books can be skimmed and the reader can choose to read some parts and not others, but all the content is available to the reader on the same level.

Roman cursive handwriting was a quickly written version of the Roman capital form. The quick nature of the process led to strokes overshooting the capital height, which eventually resulted in the ascenders and descenders of minuscule script.

Newspapers and magazines are less linear, but they are also self-contained, though unlike many books, it isn’t expected that people will read all the content of such publications.

The structure of an internet reading experience is much different: the experience is not linear but divergent. Someone looking at an internet page is usually offered a number of choices within the site, may encounter links to other sites, and may easily choose to go to another site.

Whatever the technology, one thing has not changed: in most cases, information is still communicated by typographic form.

Economies of scale

The unit cost of a book is reduced as more copies are produced – a powerful incentive to get more people to order a copy – making market appeal more important than the quality of a manuscript – unlike the case with expensive, hand-copied manuscripts. This is an unchanging characteristic of industrial production, of which printing is a foundational example: printing 1000 books today will result in a cheaper cost per book than printing 500.

Print and Web

Typographic principles and practice develop over time. The enormous change from handwriting to the printing press caused remarkably little immediate difference to the appearance of visual language. The advent of typesetting machines similarly made little change, and actually led to a revival of historical typographic forms. The internet is an even more radical change, but the biology and psychology of the reader remains the same, and typography continues to evolve from the cultural foundation of handwriting and printing. As a result, typographic principles are largely the same in print and on the Web. The biggest difference is that the reader is now an actor in shaping typography, whether by choice of device, by user controls or how they engage with interactive features on a site, or by the interactive nature of the internet itself.

TYPOGRAPHY ENTAILS TECHNOLOGICAL CHANGE

Typography, in both print and on screen, as opposed to writing by hand, has always been technically sophisticated, making use of developments in industrial technologies. While the forms of typography usually evolve slowly and incrementally (though an explosion in how basic forms were treated began with Victorian advertising in the Industrial Revolution), the methods of producing and reproducing typography have had both disruptive radical changes and ongoing technical development. The essential physical processes of most printing remained unchanged from the mid-1400s to the mid 20th century, as the process was continually refined and increasingly automated. New methods of creating and reproducing type changed the methods of producing type, increased the amount of typographic production, and, more recently, made it possible for designers to create their own typefaces.

Typography and alphabets

One of the reasons that typography took off in Europe, rather than in China where it was first invented, is that four thousand characters are needed for normal communication in Chinese writing: essential forms communicate words through visual association with meaning, though include categorical and phonetic information. The need for so many characters meant that type was impractical

The Roman alphabet on the other hand, needs only twenty-six essential characters to represent the sound of words, so even with capitals and punctuation, fewer than 100 characters are needed, making moveable type a more practical system.

Radical technologies, conservative aesthetics

The introduction of the printing process itself is an example of a new function following an established visual form. Gutenberg was trying to closely duplicate the slowly evolved written form as closely as possible while using a radically innovative process.

Typographic practice changes slowly and is highly resistant to innovation. While visual aspects can be innovative, the art of making things readable can’t be blithely innovated. Like efforts to regularize spelling, efforts to reform alphabets have been failures, except in gradual increments. Many of the typefaces we use for text today aren’t much different from those of the early 16th century. Sans serif typefaces, while relatively recent innovations, can work well for text, but again, they must be fairly conservative in form, that is, of similar proportion and weight to serif typefaces commonly used for text.

Before the development of typesetting machines, the setting of text by hand was the most time-consuming part of producing a printed document, and was therefore the economic driver of technologies such as typesetting machines and the typewriter.

Logograms in phonetic scripts

Alphabetic systems do use logographic elements; examples are symbols, punctuation and numbers, and today, emoticons and emojis. Few people would understand all of the following:

hai mươi sáu nhân với hai bằng năm mươi hai

sechsundzwanzig mal zwei ist gleich zweiundfünfzig

twenty-six multiplied by two equals fifty-two

двадцать шесть,

умноженное на два

равно пятьдесят два

However, people from most cultures would understand the logographic expression:

26 × 2 = 52

BIRTH OF THE PRINTING PRESS IN EUROPE

Carved and inked wooden printing blocks were used to reproduce multiple copies of pages a long time before the printing press. Woodblock printing arose first in China, and had spread to Europe by the early 1400s.

In Europe, typographic form began with a faithful imitation of the Gothic script that was the dominant formal writing style in Northern Europe. It was soon supplanted by type based on the humanist writing style, using Roman capital forms and humanist minuscule, modified to have Roman inscriptional style serifs. The basic technology of printing remained largely the same from the 1400s to the late 1800s. The method of producing type depended on the use of hand-carved metal punches used to produce copper moulds of each character, which in turn were used to produce multiple reverse images of the characters in a mixture of lead, tin and antimony. These were set into position by hand to form a raised reverse image of a page, then inked and pressed onto paper, enabling the production of multiple copies. When a print run was finished, the typeset page could be dismantled, and the type then reused to produce other documents.

In the earliest days of printing, decorated caps and other graphic elements were added to the page by hand. Soon, wooden, and later copper, engravings were introduced (which could be printed in other colours of ink), so that before long all graphic elements could be printed instead of being added by hand. These new technologies were eagerly adopted by printers all over Europe faster than new technologies had been in the past, because examples of them were, for the first time, mass produced.

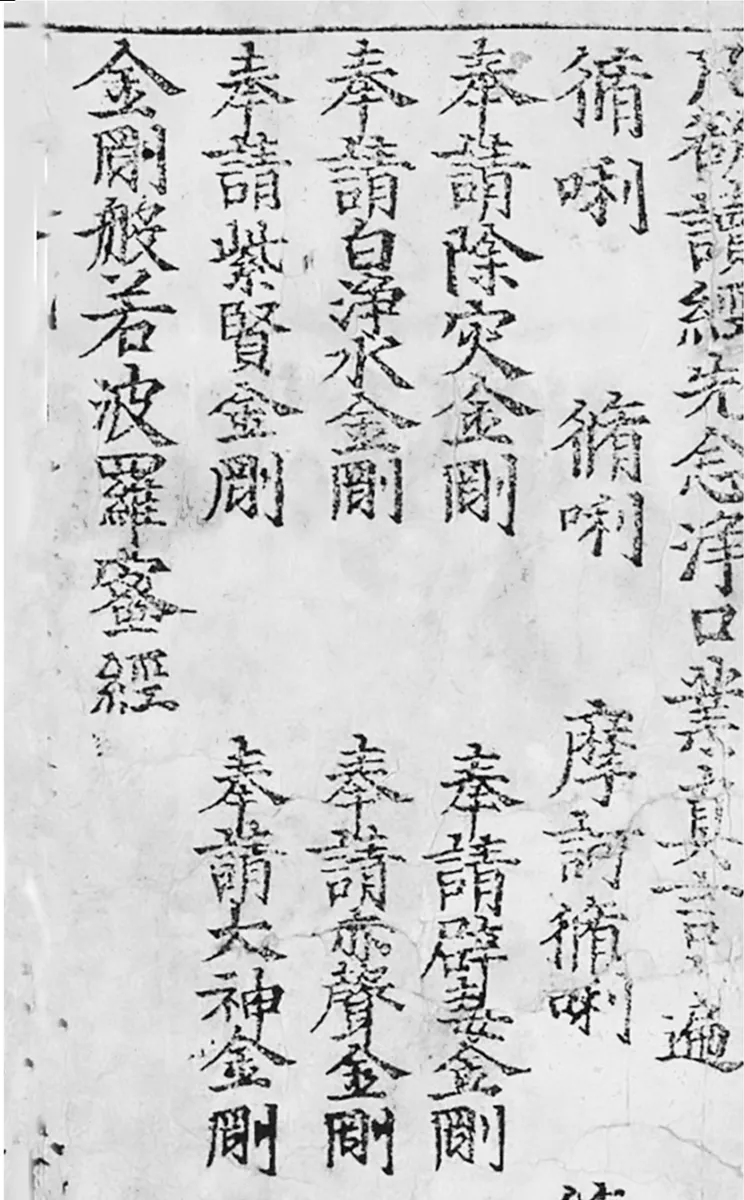

A detail from the earliest preserved printed book: the Diamond Sutra, inked and printed using carved woodblocks in China, 868 CE, 300 years before the first known moveable type, and 800 years before Gutenberg.

PRINTING LEADS TO THE MODERN WORLD

Moveable type, once created, could not only reproduce manuscripts more quickly, but could produce multiple copies thousands of times faster than the scribe, with the amount of time needed for each copy being reduced as the number of copies increased. Previously, copying two identical manuscripts had taken more or less twice as long as producing one. Using a printing pre...