![]()

1

The changes in Japanese voting behaviour and attitudes towards politics, 1980–2000

The aim of this chapter is to analyse the 20-year period 1980–2000, and assess if and how the Japanese electorate changed its attitudes towards politics and voting during this period. The 1990s was a period of great flux within the Japanese political system with many parties being created and disbanded. The Japan Socialist Party (JSP), which had been the main ‘opposition’ party in Japan,1 gradually declined in the mid-1990s and in 1996 won so few seats in the election that it became a mere shell of its former self. Between 1955 and 1993, it was the second largest party in the Japanese party system and was the largest party on the left of centre on the political spectrum. This period has become known as the 1955 system. In 1996, the JSP did extremely badly in the House of Representatives election, gaining only 15 seats (although this got worse as it only managed to get 19 in the 2000 election, 12 in 2003 and seven in 2005). A new party of the ‘left’, the Democratic Party of Japan (DPJ), was formed in 1996 and is still in existence and getting stronger.

This chapter attempts to question what changes in voting behaviour and/or public opinion attitudes towards the political parties occurred in this period. Therefore, utilising public opinion poll data, electoral data and turnout data, we shall analyse how the Japanese voters changed their attitudes towards all political parties and in particular the main party of the left. A further question will be asked: Did the DPJ automatically ‘take over’ support from the JSP or had JSP support already declined before the DPJ emerged? To facilitate this, we will compare in detail two decades: the 1980s when the JSP and the other opposition parties such as the Japan Communist Party (JCP), the Democratic Socialist Party (DSP) and Kmeit had reasonably stable opposition vis-á-vis the LDP, and the 1990s when the new parties emerged and the electorate turned into supporters of no party rather than anything else. By looking at this data in detail we will be able to establish how the JSP declined and the environment in which the DPJ was created. Turnout

Japan, like most post-industrial economies, is suffering from an acute crisis of political mobilisation that is particularly manifest in low voter turnout. Participation should arguably have increased in the past 20 years as access to

information and education has increased and Japanese demographics have changed (Topf 1996:26–50). In reality, at a time when access to information has been at an all-time high and despite attempts to make voting easier, turnout is low, although not quite as low as it was in the 1990s. Japan is readjusting from a crisis in the domestic economy, a recession of 15 years from 1990–2005, a failing bank sector which has still not fully resolved the many problems of the 1990s (where banks were on the verge of bankruptcy with the Takushoku bank actually going bankrupt), and more unemployment than Japan has ever known. In the 1990s, Japan experienced two recessions. Furthermore, since 1990, it has been in the midst of seismic changes in its attitudes towards peace-keeping activities abroad, global security, North Korea and the Peace Constitution. It also has a population which is rapidly ageing and a declining birthrate which could mean that, by 2050, the population will have dropped by 20 per cent (http://www.ipss. go.jp/p-info/e/PSJ2006.pdf, accessed 11/8/08). Life is changing and crime is increasing. For all of these reasons, Japan should be seeing increased political participation. In fact, the traditional Japanese methods of voter mobilisation are no longer as effective as they once were, and interest is far lower and consequently turnout has fallen.

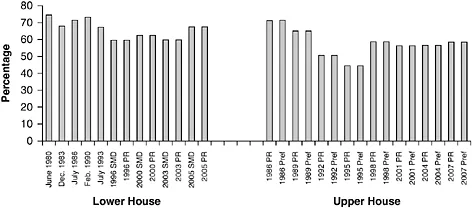

Turnout has become a particular problem in Japan since the House of Councillors election in July 1995. While it is clear from Figure 1.1 that the problem of falling turnout already existed before 1995, it was the extent of the problem of low turnout in this first national election since the historic defeat of the LDP in July 1993 that opened the eyes of the Japanese media and government to the problem. In this election, turnout fell to an all-time low of 44.5 per cent.

Turnout is higher in the Lower House than the Upper House elections and was good in 2005 for the remarkable ‘Koizumi election’ compared to recent standards

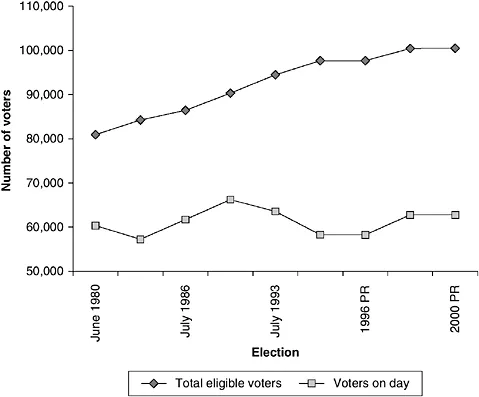

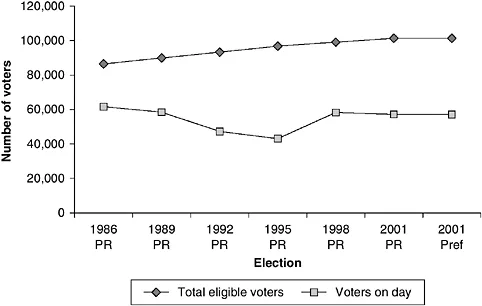

but, on the whole, it has dropped to around 60 per cent in the Lower House and the mid–late 50s in the Upper House. In Figures 1.2 and 1.3, the extent to which turnout has dropped becomes even more apparent – Figure 1.1 clearly shows the general drop in turnout at elections but it is only when turnout is seen plotted against the total number of eligible voters per election that the trend towards falling turnout during the 1990s becomes truly apparent.

As can be seen from Figure 1.3, turnout was particularly low in the ‘second-order’ elections for the House of Councillors (Norris 1997:109–124). Traditionally seen by the Japanese electorate as being unimportant elections, these have seen lower levels of turnout. Whereas the importance of the Upper House has become increasingly important since the 1989 election (because the JSP suddenly had far more influence on policy formation within the Diet as they took control of some of the committees), the electorate has not responded to this issue and turnout has dropped particularly in the Upper House.

The Japanese government started to take measures to increase turnout. Up to and including the 1995 House of Councillors election, polling stations were only open from 8am until 6pm. In 1998, polling station hours were increased to 12 hours with closing time extended to 8pm. Elections are held on Sunday to

facilitate voting for businessmen who may work a long distance from home and for long hours during the week. In another move to increase turnout, the government made voting prior to the day of the election a less bureaucratic process. Whereas before, proof of being away from the electoral district on the day of election was required, now anybody can vote in the week prior to the day of the election at the local city, town or village halls.

Nonetheless, despite ...