eBook - ePub

Living at the Edge of Thai Society

The Karen in the Highlands of Northern Thailand

Claudio Delang

This is a test

Share book

- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Living at the Edge of Thai Society

The Karen in the Highlands of Northern Thailand

Claudio Delang

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

The Karen are one of the major ethnic minority groups in the Himalayan highlands, living predominantly in the border area between Thailand and Burma. As the largest ethnic minority in Thailand, they have often been in conflict with the Thai majority. This book is the first major ethnographic and anthropological study of the Karen for over a decade and looks at such key issues as history, ethnic identity, religious change, the impact of government intervention, education land management and gender relations.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Living at the Edge of Thai Society an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Living at the Edge of Thai Society by Claudio Delang in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ethnic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Studying peoples often called Karen

Ronald D. Renard

There are many people in Burma (Myanmar) and Thailand who are known as Karen. Most of these people live in Burma. There are other people in this area who do not call themselves Karen but who are called by Karen by various peoples for sometimes divergent reasons.

So many things are unknown about the ‘Karen’ – who they are and who they are not – that one could ask, as Peter Hinton did (1983: 155–168) whether they really do exist. At the same time one could also ask, why should a people called Karen not exist since there have been thousands of articles and books on ‘Karen’ since the early nineteenth century?

Prior to that, however, there were almost no references to Karen in written literature. The earliest certain appearance of ‘Karen’ in any language in an English source was in a letter written in 1759 by Captain George Baker of the East India Company.1 Baker noted that these Carianners lived ‘in the woods, of 10 or 12 houses, are not wanting in industry, though it goes no farther than to procure them an annual subsistence’ (Stern 1976: vii).

The American Baptist missionary, Francis Mason, recognized that the word, ‘Karen’ was of Burmese origin. He noted that the Burmans ‘apply it to various uncultivated tribes, that inhabit Burmah and Pegu’ (1866b: 1). Mason himself defined the term as designating ‘a people that speak a language of common origin, which is conveniently called Karen; embracing many dialects, and numerous tribes’ (1866b: 1). At least from this time the term ‘Karen’ came into popular use.

The word ‘Karen’ has its origins in Carianner which itself is meant to represent the Mon term, kariang, which combines kha and riang. Kha is a term referring to a class of human beings that occurs in the world of Tai speakers.2 In this setting, tai are a kind of people found in valleys who were seen as possessing such civilized (i.e. Indianized) attributes as written literature, a major religion such as Buddhism, an elaborate system of kingship, law codes, and large religious edifices.3 Living beyond the pale of the Tai were forest-dwelling animist people known as kha. Riang, which is also sometimes pronounced yang, refers to various groups of forest people living around lowland tai groups and speaking dialects of what linguists call either Karennic or Waic languages in the Mon-Khmer language family.

In Burmese, kariang is pronounced kayin. This in turn is the source of the English word ‘Karen’, which retains the original ‘r’ from Early Burmese. The English either learned the term from Arakanese (also known as Yakine) or directly from the Mon. Both the Arakanese and the Mon pronounce the term with this original ‘r’. The Thai word kariang came directly from the Mon although there are many (Karen) people on the Thai side of the border, from Phetchaburi north to Chiang Rai, who were known as yang.

Those using the terms kariang or kayin or related forms were neither ethnographers nor linguists. They used such terms to denote various similar looking groups of people who might or might not be related linguistically. The ‘Black’ Karen, for example, speak a Mon-Khmer language, part of a family quite different from Karennic languages.

Although the Mon, Burmese, and Thai knew the word kariang (or kayin), they hardly ever used it in writing before the nineteenth century. According to the Mon scholar, H.L. Shorto, although the term kariang appears in a work written in about 1710 (Gawampati), there are no references to Karen in Mon chronicles (Shorto, personal correspondence). Similarly, there are no references to kariang in the Ayutthayan chronicles (Cushman 2000). The first certain occurrence of kariang in Thai occurs only during the reign of King Rama I, in 1809.4

Part of the reason for the absence of references in the chronicles is that the written literature of kingdoms such as Ayutthaya, Hanthawaddy, and Ava, recorded royal and ‘civilized’ events, such as the king’s activities, battles, and religious undertakings. The life of the common people, even ethnic Thais, went all but unrecorded. There are scarcely any references to village life, food, dress, agriculture, forestry, or livestock. This was the case for tai as well.

Not only did chronicles ignore these forest dwellers because they were ‘uncivilized’, members of these groups themselves often actively sought to avoid attracting the attention of their neighbours. For centuries they deliberately lived in remote areas out of the way of stronger groups. Take for example the account written by the American Baptist missionary, George Dana Boardman. Even to someone such as him, born in 1801 in the small town of Livermore on the edge of the frontier in Maine where he learned about wilderness firsthand, the natural obstacles were impressive.

The Karens live very much scattered and in places almost inaccessible to any but themselves and the wild beasts. The paths which lead to their settlements are so obscurely marked, so little trodden, and so desirous in their course, that a guide is needed to conduct one from village to village, even over the best part of the way. Not unfrequently the path leads over precipices, over cliffs and dangerous declivities, along deep ravines, frequently meandering with a small streamlet for miles, which we have to cross and recross, and often to take it for our path, wading through water ankle deep for an hour or more. There are no bridges, and we often have to ford or swim over considerable streams, particularly in the rainy season.… And when, after having encountered so many difficulties, and endured not a little fatigue in travelling, and been exposed to so many dangers, we come to a village, we find, perhaps, but twenty or thirty houses, often only ten, and not unfrequently only one or two within a range of several miles.

(Quoted in King 1836: 164–165)

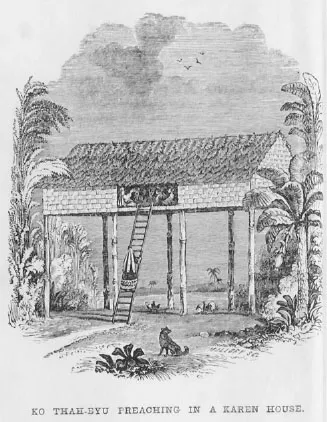

Villages were sometimes surrounded by elaborate defences of bamboo poles and pickets with intricately devised gates. Many times the reasons for such fortifications were to keep tigers and other wild animals out. Other times the object of the defences was human prowlers. In The Karen Apostle, by the Baptist missionary Francis Mason, a picture (Figure 1.1) shows a woman ascending a ladder about 4 metres in height (1846: 2). An introductory note by H.J. Ripley states that ‘many (houses) are built in this way’ (ibid. 5).

Figure 1.1 A woman ascending a ladder (from Mason, 1846: 2).

Also noted in Mason’s book was the fear the Karen had of outsiders in the 1820s. Warned by the Burmese in about 1825 that the British were fierce and dangerous, Karen in the Tavoy (Dawei) area took evasive action in ways that showed they knew how to stay hidden.

When, however, the news came that the foreigners had entered the mouth of Tavoy River, the Karens let themselves down over the wall of the city by night, and fled into the jungles. Then the Karens all ran and secreted themselves, both men and women, and children; cooking food only when the smoke could be concealed by the clouds and vapors; for they were apprehensive that, if the Burmans were overcome, they would fly also, and trace them by the smoke.

(Mason 1846: 19)

These peoples often lived in longhouses. These readily-assembled simple structures facilitated the frequent moves made by such groups of people as these. Not only would they move to avoid danger from marauding groups, but they also migrated following outbreaks of smallpox or other contagious deadly diseases. Features of some longhouses indicated their defensive nature. In one form of longhouse, a long plank or bamboo stalk, which ran along the edge of the structure, served as the pillow for many inhabitants. When danger arose, an alarm rap on the plank startled the entire house awake (Sonny Daenpongpee and Thra Hasa, interviewed 1976).5

Karen in Thailand were also found in equally remote areas. The famous Thai poet, Sunthon Phu, recorded a visit to Kariang in Song Phi Nong District of Suphanburi in about 1820. He told that when Thais running away from their (presumably Thai) masters settled next to Karen there, the Karen would help fight off or kill those who came to apprehend the runaways (Sunthon Phu 1967: 54).

Yet there were also cases where some of these ‘Karen’ wished to avoid contact even with other ‘Karen’. The Commissioner of Pegu, Colonel Arthur Phayre, described such a situation in an account of groups in Toungoo he referred to as Karen, including Paku, Mopaga, Tunic Bghai and Pant Bghai, Mauniepaga, Sgau, and Wewau, the dialects of most which were mutually unintelligible.

Up to the year 1853, the several (Karen) tribes, and it may even be said the different villages of the same tribe, lived in a state of enmity and actual warfare with each other. By open force or by stealthy manœuvre, they would capture women and children, and sell them as slaves to other tribes; while they generally put to death all grown-up men who fell into their power.

(Phayre quoted in Mason 1862: 284)

Living outside the control of people in lowland kingdoms and trying to escape the reach of related groups in nearby hills, these people often described themselves as orphans. Among the most frequently told tales of orphanhood is one about the deity Ywa and his three sons, a Caucasian, a Burman or a Thai, and a Karen, living in a time uncountable ages ago. Ywa gave them a golden, silver, and paper book, respectively. The Caucasian took this book with him to make his fortune amidst a vibrant civilization, and the Thai or Burman did the same with the silver book. But the unfortunate Karen foolishly left the book in the field where a pig tore it up and chickens ate it. Without the word of Ywa, they can now only catch glimpses of the divine message through deciphering what they see as letters on thigh bones (Mason 1866a: 231). Another popular story tells how their ancestor, Htaw Mei Paw, who had killed an auspicious boar, managed to get out of sight and so far beyond them that they could not catch up with him while they foolishly tried to boil shellfish in order to eat them, shell and all.

Historians attempting to fill the gap between the distant past when the ‘Karen’ originated and the nineteenth century face formidable obstacles. With neither a written record nor a continuous tradition of oral history, historians seeking to record the past of such ‘Karen’ peoples, who in the early nineteenth century would have disavowed such a name, have little on which to rely. The oral literature of these people, however, is indeed rich, with village headmen and religious leaders maintaining stores of tales meant for maintaining good behaviour, guaranteeing proper ritual actions and kinship relationships, as well as providing good harvests.

In this it resembles the oral literature of other shifting cultivators in the highlands, such as the Palawans of the Philippines. While not having a strong historical component, the Palawan’s oral tradition is rich in ethnic lore. Besides serving a didactic function for all aspects of Palawan life, the oral literature such as the epic, Mamiminbin (The Quest for a Wife), is expressive and complex poetry. The journeys made by the epic’s protagonist, Mamiminbin, serve to build a harmonious social space (based on the norms of Palawan custom), at the centre of which is his house and hamlet (Revel and Intaräy 2000).

The social space of these groups known as Karen is also defined in its oral literature. But remarkably, their lore from the early nineteenth century remains recorded in print. A vast store of information has been recorded in a kind of Karen encyclopaedia written from 1847–1850. Just the title indicates the scope of the work: Thesaurus of Karen Knowledge Comprising Traditions, Legends or Fables, Poetry, Customs, Superstitions, Demonology, Therapeutics, etc., Alphabetically arranged to form a Complete Native Karen (Sgaw) Language Dictionary with definitions, examples or illustrations of usage of every word (Sa Kaw-Too and Wade 1847–1850). In 1915 the first volume was revised. In the process some of the key words were also listed in English.

No other ethnic group in Southeast Asia is so well documented. Yet the Karen Thesaurus has been little used in scholarly research both because of its scarcity and because it was written in a Tavoy dialect of Sgaw not well understood by people from outside the region.

Maintaining a historical record seems to have been a task of lesser importance to these Karen groups. While many topics are covered in a work meant to be comprehensive, there is no section in the Karen Thesaurus on history. This reflects their ordinary life in which they do not preserve relics of their chiefs, but instead abandon or burn such relics at the cremation. The only village site Karen associate with a particular chief is the village’s immediately previous locale. No gravesites mark the burial places of their chiefs nor are statues or other physical representations of old chiefs customarily made. Unlike some traditional groups, such as those in Rwanda or the Yoruba states, the Sgaw and Pwo had no ‘professional historians’ who sang or told poems about erstwhile leaders. Furthermore, unlike groups such as the Bemba of northeastern Zambia who also lack professional historians but keep alive the memory of old chiefs (Robert 1973: 12–28), the so-called Karen have few such tales.

There are, however, accounts written by twentieth-century Western-educated people who proudly proclaim themselves as Karen with a past dating ...