eBook - ePub

Cultural Studies

Volume 8, Issue 2

Lawrence Grossberg, Janice Radway, Lawrence Grossberg, Janice Radway

This is a test

Share book

- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cultural Studies

Volume 8, Issue 2

Lawrence Grossberg, Janice Radway, Lawrence Grossberg, Janice Radway

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First published in 1994. Routledge is an imprint of Taylor & Francis, an informa company.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Cultural Studies an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Cultural Studies by Lawrence Grossberg, Janice Radway, Lawrence Grossberg, Janice Radway in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Culture populaire dans l'art. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

III

RECEPTION AS FLOW: THE ‘NEW TELEVISION VIEWER’ REVISITED 1

KLAUS BRUHN JENSEN

Introduction

During the 1980s, the notion of a new, powerful television viewer became widespread in both ‘administrative’ and ‘critical’ mass-communication research. Researchers within the industry have referred to increasingly selective viewers who zip, zap and graze their way through an expanding TV universe (Channels, 1988). Critical cultural studies, to varying degrees, have interpreted the prevalence of oppositional decodings as an assertion of viewer control over the medium.2 Perhaps, then, viewers may select, interpret and socially use programming for their own ends.

This article presents a critical reassessment of the ‘new television viewer’ with reference to a qualitative study of a sample of American households. While the current debates on the status of the audience cannot be covered here,3 the purpose of the study was to explore some of the structural factors affecting the scope of reception. The flow character of television, in particular, sets the terms for the viewers’ selection, interpretation and social uses of television programs.

The three flows of television

In all communications systems before broadcasting the essential items were discrete. A book or pamphlet was taken and read as a specific item. A meeting occurred at a particular date and place. A play was performed in a particular theatre at a set hour. The difference in broadcasting is not only that these events, or events resembling them, are available inside the home, by the operation of a switch. It is that the real programme that is offered is a sequence or set of alternative sequences of these and other similar events, which are then available in a single dimension and in a single operation. (Williams, 1974:86–7)

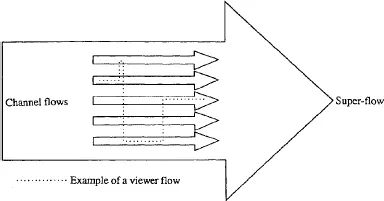

Whereas this classic definition captures an essential feature particularly of commercial television (see also Ellis, 1982), it is important analytically to distinguish three aspects of TV flow (Figure 1). First, a channel flow is the sequence of program segments, commercials and preannouncements that is designed by the individual station to engage as many viewers as possible for as long as possible. Second, viewers create their customized viewer flow from the available channels. Third, the sum total of possible sequences represents a super-flow. The interrelations between these flows, while bearing on the relative power of the medium and the viewer, have primarily been examined through aggregate measures, such as the ratings (Nielsen, 1989) and the overlap between audiences for different programs (Barwise and Ehrenberg, 1988). Cultivation studies (Gerbner and Gross, 1976) offer a relevant approach to audience-cum-content analysis, but without focusing on TV as a structured flow. Some recent research has studied the flow of individual viewers across channels (Heeter and Greenberg, 1988; Pingree et al., 1991) without, however, examining the discursive structures of the selected programming in detail. Conversely, a couple of studies have analyzed television flow as texts, but without simultaneous empirical analysis of concrete audiences. Thus, Nick Browne (1987) has argued that the networks’ historical strategy of aiming for a common denominator has resulted in the relative homogeneity of TVs ‘super-text’ (in the present terminology, super-flow) and that, further, this homogeneity is self-perpetuating because, over time, viewers have been socialized through the ‘mega-text’ of television to expect particular (super-)texts. A similar, but more cultural-optimistic perspective has been advanced by Horace Newcomb (1988), who, through a thematic reading of a ‘strip’ (viewer flow) of network programs on a particular evening, substantiates the argument that TV represents an open forum (Newcomb and Hirsch, 1984) for diverse political and cultural issues and viewpoints. Surprisingly, however, Newcomb's reading does not include the commercial breaks. And, as in most other studies, no simultaneous empirical analysis of audience and contents—of viewer flows selected from the channel and super-flows—was carried out.

Figure 1. The flows of television

Methodology

This empirical study produced a ‘reverse video’—a record of the viewer flow in specific households—by asking the respondents to make all channel changes with their VCR running and attached to their main TV set. The recordings were made on a Wednesday evening in the middle of the TV season (1 February 1989), an ‘average’ night of regular programming. Respondents were asked to watch some TV between 7.00p.m. and 9.00 p.m. but not necessarily for the whole period. In addition, respondents filled in basic questionnaires about demographics and television use as well as any comments especially concerning their channel changes, hence offering additional information about the recordings, which were examined as the primary objects of analysis. The local TV Guide (1989) documents the availability of network, independent and public TV stations in the super-flow, as well as additional cable channels, to which half of the sample had access.

Table 1. A power index of television

A sample of twelve video households from the Los Angeles metropolitan area was selected by a local market research firm. The aim was to explore as wide a range of household types as possible in terms of household size and socio-economic status; the actual sample was predominantly white and middle class, but included both young and elderly viewers as well as households with/without children and with one/two parents.

Before reporting two sets of findings, it should be emphasized that while relying on a small sample, the study may identify some basic structures particularly of the viewer flow. These structures lend themselves to further research on a representative scale, and they also complement previous interview and observation studies on the decoding and social uses of specific texts or genres. Although the design entailed an intervention into daily routines, the households were familiar with the video technology, and were not required to watch for the entire two-hour period. The recordings, in sum, document some actual instances of reception as flow which may question the notion of a new, powerful viewer.

A power index of television?

The first form of analysis examined the number of channel changes made by the respondents, compared to the content changes resulting from a channel introducing a commercial, a preannouncement, or a program segment. The ratio between these two kinds of changes may be interpreted as an index of the relative power of TV and its viewers, in the sense that each change controls which flow segment is subsequently shown on the screen. The capacity to control which texts and genres one is to receive can be defined as a minimal form of cultural self-determination. This analysis thus initially accepts the terms of the industry's argument that increasingly viewers select the segments they want to watch while avoiding not least the commercials. Simultaneously, however, the analysis prepares the way for an immanent critique (Bernstein, 1991:315) of the logic behind the argument. Even on its own terms, the industry's conception of the selective viewer may not hold. Table 1 reports the number of viewer-initiated and channel-initiated changes. The channel-initiated content changes include only changes between commercials, preannouncements and program segments, not between scenes of fictional series, news stories, or music videos, and only simultaneous changes of image and sound. The viewer-initiated channel changes include the initial switching on of the set. The figures suggest the relative control of the medium, at least in this sample of viewers and the super-flow at this time of day, even if the findings may call for replication on a representative sample.

Rather than concluding in quantitative terms that hence viewers are powerless, or that more frequent channel changes as such would make them more powerful, the purpose of the analysis is a preliminary, immanent critique of the common conception of the ‘new television viewer’ in industry rhetoric as well as some research and public debate. The super-flow establishes particular conditions of reception, which are not eliminated through a measure of zapping or oppositional decodings. The next step, then, is to ask which specific range of discursive meanings are available in the viewer flows that audiences construct for themselves from the super-flow. One answer is suggested by a second form of analysis examining two types of discursive structures—intertextuality and super-themes—across the different genres of flow.

Flows, genres and super-themes

The genres which predominate in American television on weekdays, between 7.00p.m. and 9.00p.m., especially present an opportunity for viewers to negotiate the relationship between private and public areas of life. They are three: situation comedies, tabloid journalism (e.g., A Current Affair, Entertainment Tonight), and tabloid science (e.g., Unsolved Mys teries). In social-structural terms, the genres of this period serve to mediate between the public life of work or school and private life (Scannell, 1988:26). On the one hand, situation comedy is a fictional genre which, though focusing on the home, raises social issues pertaining to families and individuals; on the other hand, the tabloid programs present facts about the world which may affect families and individuals in various respects. Whereas the analysis returns to some of the variations of how viewers combine these genres, it may be noted here that, despite other options including cable programming, the households themselves also emphasize these three genres in their actual viewer flows. It is also interesting to note that some of the subscribers to pay movie channels would only watch part of a movie before selecting another channel, thus apparently treating pay channels as simply elements of the super-flow.

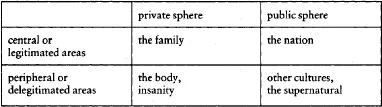

The viewer flows were analyzed with reference to a category of super-themes, defined as highly generalized concepts which may establish meaningful relations between the generic realities of TV programs and the everyday realities of viewers. Previous research in the United States and Denmark have identified such super-themes structuring the reception of TV news as well as the everyday conceptualization of politics more generally (Crigler and Jensen, 1991; Jensen, 1988). Thus, although the study did not interview or observe viewers, the actual viewer flows may be examined as potential structures of meaning, as selected by recipients, and may be interpreted with reference to the theoretical categories of earlier reception studies. The configuration of super-themes is summarized in Figure 2, and discussed below.

Figure 2. Super-themes of television flow

Flow as discourse

The super-themes were inferred from a detailed analysis of three categories of the TV discourse: actors, coherence and presuppositions (for surveys of discourse analysis, see van Dijk, 1991; Jensen, 1987).

First of all, the verbal and visual representation of actors and their actions carry a range of positive and negative connotations (Barthes, 1964:89–94). Further, such representations cumulatively imply appropriate public and private roles of actors. To exemplify, the flow of one household (Household 2) featured Charles in Charge, A Current Affair and Unsolved Mysteries, in which actors related to all four super-themes appeared. A Current Affair reported on a doctor's sexual abuse of a patient, a Congress politician allegedly having sex with teenagers, and an update of a story on marriage fraud. Articulating a discursive boundary between the family and a deviant private or sexual life, and employing a terminology of insanity, the reports on these cases establish a contrast with the ‘normal’ family life of Charles in Charge. Similarly, a contrast is established between the nation and supernatural dangers. Unsolved Mysteries included coverage of the exploration of Mars, where traces of ancient civilizations may be found. In reference to ‘America's romance with Mars’, it is significant that ‘America’, not ‘humanity’ or ‘Earth’, enters into the relation with other forms of life. Supernatural powers in the form of UFOs also appear briefly in Charles in Charge as a threat to family security.

Second, the discursive coherence of TV flow contributes to developing the superthemes. Coherence is carried not just by the verbal and visual structures and sequences of television, but as importantly by the functional relations between sequences, which may indicate a causal or temporal relationship or a conclusion (van Dijk, 1977). Such relations obtain both within and between the three types of flow segment. To exemplify coherence within a segment, Household 2 selected Unsolved Mysteries, which included a classic narrative comparable to folk-tales (Todorov, 1968). This was the story of a little girl who, when living with her parents in Austria as a refugee following World War II, was taken to a Christmas party by an American soldier. Now, through the intervention of this program, the two have been reunited in the US. The story of their lives, then, is told through categories such as The First Encounter, Separation, Quest and Reunion.

Similarly, coherence is established across segments, not least through the commercials. In the course of the video from Household 2, several commercials represent other cultures with an implied contrast to the American nation. A soldier wearing a Nazi uniform and speaking with a heavy German accent drives his tank up to a fast-food stand, and discovering the low prices, he decides to ‘fill up the tank’. The immediately following item advertises a new book with reference to an ominous atmosphere in a Japanese context. And, several later commercials featuring a cream cheese depict a band of dancing cucumbers singing a Latino tune and wearing Mexican hats. Another commercial in Household 2’s flow is a parody of a United Nations assembly debating heatedly where to have dinner, and the commercial offers the solution: a local hamburger chain.

Finally, presuppositions carry the fundamental assumptions of a discourse (Culler, 1981; Leech, 1974). While they may be explicit, presuppositions are often the implicit premises of an argument or narrative, constituting...