Practitioners of EU law have for decades criticised the institutional scheme for the enforcement of EU competition law. Originally designed as an administrative procedure in the 1960s for the enforcement of a seemingly obscure field of Union law, the procedural regime contained in Regulation 17 and the succeeding Regulation 1/2003 has since been the backdrop for many of the most epic court cases in the brief history of the EU. In the early 2010s, litigators tested an argument about the compatibility of the institutional scheme with regards to recent developments towards a gradual criminalisation of competition law breaches and the increased prominence of individual procedural rights following the elevation of the CFR to a Union constitutional status.

A.The KME/Chalkor Argument

Leading up the KME-Chalkor litigation, parallel developments had occurred in two unrelated fields of EU law that, when taken together, gave rise to doubts about the compatibility of EU’s competition procedure with obligations to ensure procedural fairness. More specifically, these doubts concerned the procedure for imposing fines in cartel cases and the way in which the Court exercised its power to review such decisions.

The first development arose following the modernisation of the competition enforcement regime with the entering into force of Regulation 1/2003, and is well explained by data published by the Directorate General (DG) Competition.4

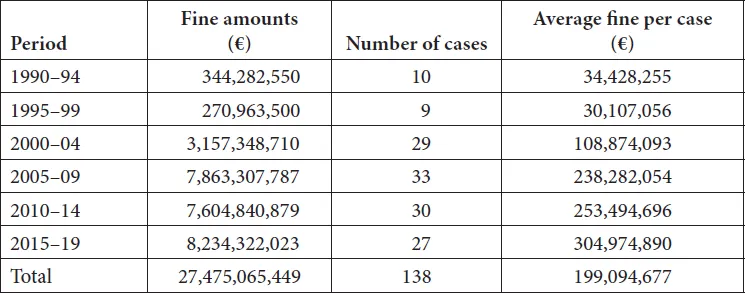

Table 1.1 Cartel cases where fines were imposed by the Commission 1990–2019 (amounts adjusted for Court judgments – updated 7 November 2019)5

In the 1990s, the average cartel fine amounted to approximately €30 million. By the early–mid 2000s, the fines had increased substantially and had by the late 2010s reached an average of €305 million.6 This increase coincided with the modernisation programme of the late 1990s and early 2000s, and was supported by a conscious use by DG Competition of condemning rhetoric to raise the social stigma of engaging in a conduct prohibited by the EU’s competition provisions.7 An example of this can be seen in a speech given by Mario Monti, then Commissioner for Competition, in Stockholm in September 2000:

Cartels are cancers on the open market economy, which forms the very basis of our Community. By destroying competition they cause serious harm to our economies and consumers. […] In the words of Adam Smith there is a ‘tendency for competitors to conspire’. This tendency is of course driven by the increased profits that follow from colluding rather than competing. We can only reverse this tendency through tough enforcement that creates effective deterrence. The risk of being uncovered and punished must be higher than the probability of earning extra profits from successful collusion.8

Describing the conduct of breaching Article 101 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the EU (TFEU) as the infliction of a cancer on the economy and accusing the entities engaged in such activity of conspiracy against the general public was probably not what the original signatories of the EEC Treaty of Rome envisioned when they delegated the supposedly minor administrative issue of enforcing the competition provisions of the Treaty of Rome to the Commission in the early 1960s, but is consistent with a contemporary trend in competition law enforcement in many jurisdictions.9

The later development, which raised worries about the EU’s competition procedure’s compliance with fairness standards, concerned the constitutional project of the EU. In line with ordoliberal ideas popular at the time, the original EEC Treaty of Rome was often viewed as an economic constitution, referring to the imperativeness of the four free movement principles and the ancillary provisions on competition. Later, the Court gradually recognised more traditional rights principles as being part of the EU’s constitutional framework, despite their absence in the Treaty of Rome. This was in part due to a necessity following the establishment of the supremacy doctrine in Costa v Enel, which created the potential for EU laws to override constitutional rights in the Member States, including traditional rights provisions.10

In Internationale Handelsgesellschaft of 1972, the Court claimed that

respect for fundamental rights forms an integral part of the general principles of law protected by the Court of Justice. The protection of such rights, whilst inspired by the constitutional traditions common to the Member States, must be ensured within the framework of the structure and objectives of the Community.11

From then on, it has been assumed that traditional rights form part of the constitutional framework of the EU, and since the judgment in Rutili in 1975, the rights under the ECHR have been explicitly acknowledged in the Court’s case law.12

Although tacitly recognised as being part of the primary law of the EU from the 1970s through the Court’s case law, an effort was not made to codify a clear list of rights for the EU until in 1999. Then the European Council decided to commission the drafting of a CFR to a senior body of representatives that adopted the name ‘the European Convention’. The Commission, the European Parliament and the Council of Ministers proclaimed the draft as the CFR in the Nice summit of 2000, but simultaneously decided that ‘the question of the Charter’s force [should] be considered later’.13

An updated version of the Charter was supposed to become part of the European Constitution of 2004, which failed in the ratification process.14 A reference was also made to an updated version of the Charter in the Lisbon Treaty of 2007, with the intention of giving it a comparable hierarchal legal status as the founding Treaties of the Union. When the Lisbon Treaty entered into force on 1 December 2009, the CFR thus acquired a Treaty status within the EU system of laws, which as a consequence made traditional rights for the first time an explicit part of the codified constitutional framework of the EU.15

For the purposes of the KME/Chalkor litigation, this gradual constitutional development with regards to traditional rights, gave rise to an argument that the institutional arrangement of competition enforcement, which was instituted by the Treaty of Rome in 1957 and by Regulation 17 in 1962, was no longer compatible with the recognition of the right to a fair procedure enshrined in the newly codified Article 47 CFR.16

Independently, these two separate but parallel developments – of criminalisation of competition law breaches and the constitutionalising of traditional rights – could each warrant a reconsideration of whether the institutional architecture of competition law enforcement was compatible with the current norms of procedural fairness. When combined, these distinct developments formed a powerful argument that required close attention by the stakeholders of the competition law enforcement regime. Arguably, the threshold of rights protection had risen over time: first following the implicit recognition of rights in the EU system of law; and later through an explicit codification. At the same time, the protective interests had also increased: on one hand as the result of increased social stigma against competition law breaches; and on the other hand, as the result of increased economic consequences for those caught committing such breaches. Thinking about the standard of criminality and the standard of a moral entitlement to a fair process as two separate constants, against which the factual context of a case is assessed, the argument of the KME/Chalkor litigation was that the substance of the rights constant had changed and that the factual cir...