eBook - ePub

Bent Street 3

Australian LGBTIQA+ Arts, Writing and Ideas 2019

Tiffany Jones

This is a test

Share book

- 252 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Bent Street 3

Australian LGBTIQA+ Arts, Writing and Ideas 2019

Tiffany Jones

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

Bent Street is an annual publication that gathers essays, fiction, poetry, artwork, reflections, interviews, rants and raves, to bring you 'The Year in Queer'. Bent Street features works from LGBTIQA+ creators in 2019, with themes arising from 2019, and the view backwards and forwards.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Bent Street 3 an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Bent Street 3 by Tiffany Jones in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Littérature & Collections littéraires LGBT. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

LittératureSubtopic

Collections littéraires LGBTWHAT LGBT PARENTS WANT IN SCHOOLS

TRENT MANN,

TIFFANY JONES

Changes in how LGBT parents are viewed

LGBT parents are becoming increasingly common in Australian schooling communities (ABS, 2013; Dempsey, 2013; Perlesz, et al. 2010). Research has not explored the ability for schooling communities and institutions to reflect the now greater levels of acceptance and the push for inclusive supports for LGBT parents (Leland, 2017; Mercier & Harold, 2003). This research is particularly pertinent as attitudes, beliefs and stereotypes of Australians seem to have changed in recent years (ABS, 2017). This article reports on a survey of LGBT parents designed to understand their views on supports.

Literature on LGBT parents influencing schools

The literature on LGBT parents stems mainly from U.S. and U.K. samples emerging from the 1960s, with growing literature from Australia (Goldberg, 2011; Kosciw & Diaz, 2008; Lindsay, et al. 2006). The research into LGBT parents has developed from anecdotal aetiological studies to exploring LGBT parent experiences within specific contexts. There are four main types of dominant conceptual framings for studies on LGBT parents (see Table 1). Over time, the emphasis has variably included:

- Anti-LGBT Studies—which take an outright negative view of the group’s identities;

- LGBT Parent and Child Development Studies—which show some suspicion towards the group’s influence on kids;

- LGBT Parented Family Diversity and Family Functioning Studies—which consider the group’s experiences of stigmatisation; and

- LGBT Parents in School Contexts Studies—which consider discrimination.

All of these conceptualisations focus on negative framings of LGBT parent identities or experiences, showing a suspicion of the possibilities for the group itself or their engagement with their children’s worlds. Power et al.’s (2012) study differed in how it showed the internal resilience of the group across their experiences; however, following Gahan’s (2017) exploration of external provisions broadly, we saw a need to study assistance for the group in school services specifically.

New tasks for LGBT parents studies

Farr, Tasker & Goldberg (2017) state current studies on LGBT parented families have focussed on addressing public debates of sexual minority parent family structures without theoretical frameworks informing research. Whilst there are clearly many ideas on what might support LGBT parents in schools emerging—policies, staff training and so forth; the impacts of such supports for LGBT parents in practice are not yet directly ‘research-based’ or ‘research-proven’. The perspectives of LGBT parents on the benefits of inclusive school strategies have been overlooked in previous research (Cloughessy & Waniganayake, 2013). Studies now must aim to focus on the impacts of supportive factors and the ideals for supports that LGBT parents themselves can lend insight on, contrasting to existing literature adopting a largely deficit approach to LGBT parents in school contexts, and overlooking supportive constructs that may offset the stressors experienced by LGBT parents. There is also a diversity to LGBT parents—often treated as a homogenous group (Perlesz et al., 2010)—which must not be overlooked.

Further, Farr, Tasker and Goldberg (2017) point out that theoretical frameworks were inadequately applied or absent from most LGBT parenting research. Robinson (2002) argues ecological theory offers a more detailed conceptualisation of family engagement within institutions; directly applicable to considering LGBT parents’ needs in schools. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory (1974) could particularly be developed to generate new research in the field (Farr, Goldberg & Tasker, 2017). Bronfenbrenner states that an individual is nested within five broad ecological systems (See Figure 1). At the centre is the Individual (e.g. an LGBT parent), including all their characteristics. The study was mainly concerned with the Microsystem level of external influence surrounding LGBT parents which included environmental variables that directly interact with the individuals and their families.

Figure 1: Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Theory of Development (1974, p.47).

Survey methodology

A mix of qualitative and quantitative data have the potential to provide stronger results by drawing on the strengths of each (Creswell & Garrett, 2008; Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011; Johnson, Onwuegbuzie, & Turner 2007). For this study, since psychological and social phenomena are inherently complex, and because multiple sexuality and gender groups were being included, both qualitative and quantitative were necessary to best draw out differing experiences and perspectives (Creswell & Garrett, 2008; Creswell & Plano Clark, 2011). An online survey was developed to explore the demographic diversity of Australian LGBT parents, their child’s school characteristics and their perceptions of the benefits of various supports in Australian schools. Care was taken to ensure the survey did not rely on schools as distributors, as discussion of sexuality and gender themes in education settings can embarrass LGBT people, or expose them to stigma and discrimination (UNESCO, 2019, p.16). A qualitatively driven mixed method design was selected for the survey, to employ the strengths of quantitative and qualitative research (Johnson & Christensen, 2014). This allowed open questioning to capture the complexities of sex and gender identity likely to be seen across a mixed LGBT group.

Participants were recruited from the general Australian LGBT parent community with children in Australian schools via convenience and snowballing non-random sampling techniques for 10 days in 2019. In total, 150 complete and incomplete surveys were submitted to Qualtrics. However after the removal of non-responses and those outside the target group, the participants included 73 LGBT parents with children currently enrolled in Australian schools. Analysis of responses to open-eneded questions was aided by Leximancer, which identified the dominant themes and most typical quote excerpts for each theme. This is useful for ensuring the research did not focus only on outlier, emotive examples, and considered what was most common.

LGBT parent demographics

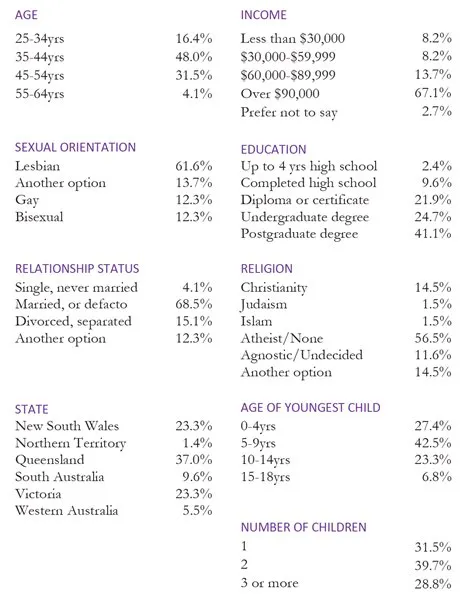

Participants were aged 25-64yrs of age, and almost half of the sample were 35-44yrs (Table 1). They were mostly located in eastern states; primarily Queensland followed by New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, Western Australia and the Northern Territory. The gender of parents in the sample was predominantly female followed by male, other and transgender. Of those who responded ‘other’, four respondents identified as non-binary, one as trans-male, one as trans-female and one as female-bodied. The sample was predominantly affluent and highly educated. Nearly 70% of the sample earned annual incomes over $90,000 and over 60% held university (undergraduate and postgraduate) qualifications. Close to 70% of the participants were in married or committed relationships followed by divorced, another option and single. Of those participants selecting ‘another option’, five were dating, three were single and one was in a polyamorous relationship. Table 2 also shows over half of participants identified as Atheist, followed by Christianity, another option, Agnostic/undecided, Judaism and Islam. Of the four indicating another option, six identified as pagan, two as none, one as yoga and one as ex-Christian. Most participants indicated having two or more children. The age of participants youngest child ranged from 0-18yrs; most children were aged under 14yrs.

Table 1

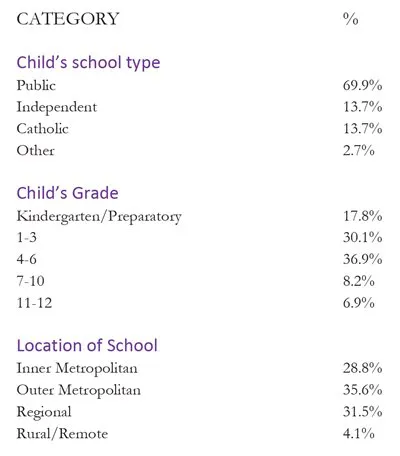

Microsystems—school type, location & supports

The physical characteristics of LGBT parent school microsystems are displayed in Table 2. The majority of children in the sample were enrolled in Public schools, followed by Catholic, Independent and Other. Of those respondents who indicated other, one was in a special needs school and one was in an Anglican private school. Over 60% of the sample had children enrolled in primary school, followed by Kindergarten/Prep, and high-school. The majority of the sample had children enrolled in schools in outer metropolitan areas, followed by regional, inner metropolitan and rural locations.

Table 2

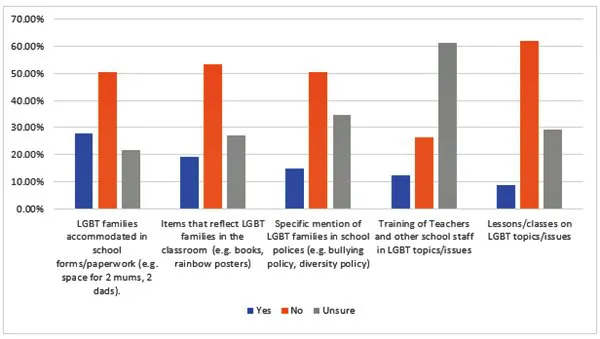

The microsystem environmental characteristics of participants were explored by asking about LGBT parents awareness of their child’s school providing supportive strategies identified in school guide research. As can be seen in Figure 2, inclusive school forms (27.8%) was the most common supportive strategy present in schools followed by items that reflect LGBT families in classrooms (19.3%), specific mention of LGBT families in school policy (14.8%), teacher training in LGBT topics/issues (12.3%), lessons on LGBT topics (8.9%) and mention of LGBT family structures in school brochures/documents (7.0%). The least likely school supports provided for by schools included mention of LGBT families in brochures or documents (73.7%), followed by LGBT inclusive curriculum (62.0%), items that reflect LGBT families (53.5%), LGBT inclusive school forms (50.4%), LGBT families in school policy (50.4%) and teacher training in LGBT topics or issues (26.3%).

There was a significant amount of uncertainty in the sample regarding the provision of many supports: particularly teacher training in LGBT topics/ issues (61.4%) and explicit mention of LGBT families in school policy (34.8%), followed by LGBT lessons (29.2%), LGBT reflective items in classrooms (27.19%), LGBT inclusive forms and documents (21.74%) and mention of LGBT families in brochures or websites (19.3%).

Figure 2: Support strategies reported by Australian LGBT parents in schools

LGBT parents on the usefulness of supports

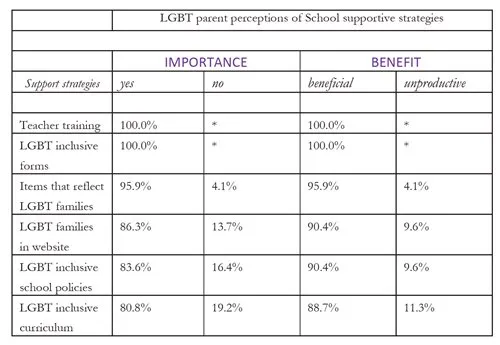

Table 3 shows that over 80% of LGBT parents deemed all suggested supportive strategies as important and beneficial in forming positive school environments; teacher training and LGBT inclusive forms were unanimously affirmed. In the comments, LGBT parents showed concern that teacher training needed to discuss the range of family constellations rather than present a homonormative ideal whether they mentioned single parents or indigenous kinship models. In the most typical examples according to computer analysis, Kerry (46 yrs, Victoria) said ‘it should be embedded in being educated in broader not common family structures, ie accepting of diverse family structures not just LGBT’; Sophia (38 yrs, Queensland) said, ‘there is a risk that education like this becomes tokenistic. LGBT families are as diverse as any other family. There is a risk that assumptions are made’. This concern for diverse family structures was also shown in the comments on forms. Trinity (50 yrs, Victoria) said ‘I often have to modify forms in order to accurately describe the relationship between my son and my partner’ and Ben (49 yrs, Queensland) commented that some issues could easily be resolved since ‘forms can easily be gender inclusive (simple language such as parent)’.

Table 3

Perceived importance and benefit of supportive structures in school environments.

Positive experiences & future hopes

Most (51 of the 73) participants reported that they had positive one-off or person-specific positive experiences within schools (17 said no, 5 did not respond). The predominant theme was instances of staffs’ sensitive treatment of the families during days most likely to cause distress or difficulty. For example, Zoey (46yrs, NSW) said ‘At our intake interview our daughters’ whole family was welcomed; this included lesbian mum, trans parent and her two dads … was just a non-issue’. Mary (37yrs, Victoria) said, ‘They are always accommodating around Mother’s day and Father’s Day’ (Mary, 37yrs, Victoria). Some parents talked about particular teachers who were very careful to be inclusive in their langu...