![]()

1

CHAPTER

READING THE ENTRAILS

Origins, motives, sources

Is it possible to predict the direction crime fiction will take now that we are well into a new century? Initially, the auguries are bad: many classic genres (notably the police procedural) have undergone a distinct hardening of the arteries, as inspiration gives way to cliché and innovation to repetition. As all hard-pressed crime writers know, it becomes increasingly tough to come up with something new. Editing Crime Time magazine, most of the letters I received lamented the difficulties of tracking down that one fresh and inventive novel among much that is – shall we say – warmed over. And yet crime fiction remains (pace books about witches, wizards, dragons and spurious codes) one of the few evergreen areas of modern publishing, with fresh trends continually appearing, including the Nordic noir wave (still healthy) and domestic noir, both covered herein.

While a case can be made for the origins of the crime novel lying in the 19th century, equally plausible cases can be made for antecedents even further back. It is cold comfort that, according to the Bible, when Cain slew Abel, the third human ever created had managed to murder the fourth. A little later, Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex, a search for the truth about himself, has all the classic ingredients of the psychological mystery, even down to the final painful acquisition of knowledge leading to the destruction of the protagonist, and most of his family. Noir territory, indeed. No less dark are William Shakespeare’s pivotal assassination dramas Julius Caesar (think conspiracy theories) and the malign ‘Scottish play’ (for Lady Macbeth read almost every femme fatale to glower from the silver screen). But, while we can possibly shoehorn the Bible, Sophocles and Shakespeare into the genre as progenitors of crime fiction, the concept of the cliffhanger mystery novel took off in the 19th century almost equally and simultaneously in gothic, Romantic and realist writing. Where the gothic writers preferred a darkly supernatural sense of suspense and denouement, horribly real cops, secret agents and villains occur regularly in the work of Honoré de Balzac, while the world’s first dogged detective (albeit also a blackguard) trails Victor Hugo’s Jean Valjean through almost every page of Les Misérables (1862).

An obsession with crime, the dark, nefarious underworld and just retribution was revealed in the popularity of publications such as The Newgate Calendar, and by the end of the century lurid ‘penny dreadfuls’ and ‘shilling shockers’ vied for bookstand space with Bram Stoker’s comparatively respectable parlour-piece Dracula (1897), just as the world’s first serial killer, Jack the Ripper, was stalking the streets of Whitechapel, and canny film producers were seeking sensational stories to project onto the minds of a willing and hungry public huddled in circus tents.

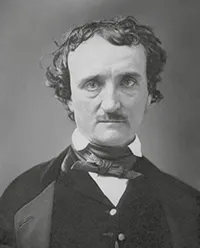

But the most significant innovation of the 19th century was that of American polymath Edgar Allan Poe’s C Auguste Dupin, who first displayed the requisite cool ratiocination and ability to marshal facts that were to become the sine qua non of the investigative detective. Poe even created the less brilliant follower for his detective (in order that the hero’s mental pyrotechnics might be displayed more satisfyingly). Poe was greatly admired in France, and translation of his work by Baudelaire (among others) was to spread his influence far beyond the provincial Stateside streets of Baltimore and Richmond.

Leaving aside Charles Dickens’ Inspector Bucket and Mr Nadgett (who certainly deserve namechecks in any overview of crime fiction) and the master’s unfinished murder novel The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870), it is tidier to settle on his friend Wilkie Collins, with The Woman in White (1859) and The Moonstone (1868) as the first instances of great crime novels. A reacquaintance with these two most readable books demonstrates that many of the key elements we recognise so well (notably the hyper-intelligent, hyper-ingenious villain, the slightly dim hero whom we follow piecing together the mystery, and a narrative crammed full of delicious obfuscation) are firmly in place. But it is also salutary to note that one element – the elegance and polish of the prose – has become less common since those distant days. Whenever the diehard crime reader picks up a modern novel as well written as Collins’ were, it’s a cause for some celebration. Of course, eventually the genre had to accommodate lean, pared-down prose as much as Collins’ more intricately orchestrated language. It was a matter of economics, cut-and-thrust suspense, and popular appeal.

Edgar Allan Poe

(1809–49)

Orphaned, a failed soldier, a bankrupt gambler and an alcoholic incapable of holding down a job, forced to live with his child wife’s mother, and eventually dead in a gutter aged 40. How could this man become an outstanding poet, essayist and progenitor of at least five literary genres: the short story (or tale), horror, science fiction, psychological fiction and the crime novel? Probably his background predisposed him to introspection, gloom and despond, but the elegance of his style and intricate intellectual curiosity give even his darkest works a burnished gleam. The obsessive protagonists of many of his tales prefigure both the criminals and sleuths of later writers: ‘The Tell-Tale Heart’ (1843) deals explicitly with a murderer’s guilt, as does ‘The Cask of Amontillado’ (1846). But it is the three tales featuring the detective C Auguste Dupin (massively influential on Conan Doyle), who uses observation, logic and lateral thinking to solve crimes, that claim primacy for crime enthusiasts. ‘The Murders in the Rue Morgue’ (1841) is the prototypical locked-room mystery; ‘The Mystery of Marie Rogêt’ (1842) was based on an actual case in New York and introduces the problem of reconstructing what happened to a murder victim in the last days of her life; ‘The Purloined Letter’ (1845) involves a psychological game to reveal a blackmail trophy.

The Mystery Writers of America award, the Edgar, is named in his memory.

And it was another writer, from the next generation, who was to bring the concept to its greatest fruition – a marriage of author and character that few have achieved since.

Arthur Conan Doyle’s creation of the master detective Sherlock Holmes – as noted above – owed much to Poe’s Dupin (the latter is even discussed in the stories), but his extension of the concept into a considerable canon of work that stretched over 40 years demonstrates a craftsmanship that simply beggars belief. His masterstroke, of course, was to take the relationship between the unconventional, brilliant investigator and his assistant and develop it into something rich and resonant. Again and again, the sheer pleasure of the stories comes from the nuances of the relation between Holmes and Watson as much as from the plot revelations (some of which, as Conan Doyle well knew, were outrageously implausible), and the way in which details of Holmes’s character were freighted in (the violin, the depression caused by inactivity, the ‘7 per cent solution’, etc.) ensured that Conan Doyle’s detective became probably the best-known Englishman in fiction, and one of the first truly international bestsellers. His influence is felt to this day, with writers such as Joe Ide providing contemporary spins on Holmes-like detectives.

At about the same time as Conan Doyle was concocting Holmes, other criminal currents were stirring. In Russia, Fyodor Dostoyevsky was creating a template for the existential psycho-killer (Crime and Punishment, 1866) and the familial destruction novel (The Brothers Karamazov, 1880). And a French realist dealt with a range of shady lowlife scenarios and godfathered the domestic ménage à trois that results in murder. Two lovers who can’t keep their hands off each other and who have sex on the floor; an inconvenient and unattractive husband who has to be removed. I know – you’re thinking of James M Cain’s The Postman Always Rings Twice (1934)? Or one of its many imitators? No, another writer got there earlier… Émile Zola, with his carnal and edgy Thérèse Raquin in 1867. Who can write about sex like Zola these days, with authors all flinching in advance at the thought of nomination for the Bad Sex Award or political correctness? What about this passage:

Then, in a single violent motion, Laurent stooped and caught the young woman against his chest. He thrust her head back, crushing her lips against his own. She made a fierce, passionate gesture of revolt, and then, all of a sudden, she surrendered herself, sliding to the floor, on to the tiles. Not a word passed between them. The act was silent and brutal.

The Vintage Classics translation by Adam Thorpe makes one realise why Zola was so shocking in his day.

The inherent brutality (as well as the concupiscence and violence) of Zola’s work found expression in another infernal triangle in the blunt and excoriating La Bête Humaine of 1890 (the Oxford World’s Classics version is translated by Roger Pearson), a richer, more complex experience than Thérèse. The unlucky trio here are the eponymous ‘human beast’ Lantier, gripped by a hereditary madness and a desire to murder; Séverine, an object of lust for men, yet someone who retains an unsullied centre; and Roubaud, her brutal husband who cuts the throat of one of her ex-lovers. American paperback editions emphasised the steaminess (calling it The Human Beast and adorning the jackets with copious cleavage); English editions tended to stick to the original French title. The book, though, is about far more than a sordid homicide: Zola’s targets include the French judicial system (which he was to excoriate during the Dreyfus affair) and there is a brilliant realisation of the world of railways and railwaymen. My ad...