1

Imperial Germany, 1871–1918

The term ‘Germany’ had no real political significance at the beginning of the nineteenth century. The numerous states that made it up were loosely bound by their membership of the old Holy Roman Empire. The German Empire, or Second Reich, was created in 1871, and was founded on an unequal alliance between the national and liberal movements and the conservative Prussian state-leadership. The German Empire included Prussia, the kingdoms of Bavaria, Saxony and Württemberg, eighteen lesser states, three free cities and Alsace-Lorraine. It has been stated that the Prussian Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck, united Germany as the result of a series of successful military wars. However, closer examination reveals that the conditions for unification had been achieved before Bismarck came to power.

During the nineteenth century there were three major steps towards unification: the creation of the German Confederation (1815); the formation of the German Customs Union (Zollverein) (1834); and the period of the decline of Austrian influence (1852–64). Brought about by naked militarism, the creation of the German Empire appeared to have fulfilled Bismarck’s prediction of 1862 that Prussia would unite Germany by ‘blood and iron’. In fact, the Empire had been established only after numerous compromises had been made and was immediately open to the criticism of being incomplete. Certainly when measured against the great aims of the 1848–9 Revolution—to create unity through freedom to build the state on new political, economic and social foundations—the founding of the Empire signified a defeat for middle-class liberalism. By and large, however, the majority of people warmly greeted the achievement of national unity. The story of imperial Germany after the euphoria of 1871 was the failure to adapt its institutions to the newly developing economic and social conditions.

Left-wing liberal critics dismissed the Empire as an incomplete constitutional state. The liberals claimed that it should be governed on a wider parliamentary basis. A largely powerless parliament (Reichstag) was complimented by an upper house, the Federal Council (Bundesrat), which was made up of delegations from the separate states (not, therefore, representative of the German people as a whole). While the Reichstag possessed rights of veto, legislation was initiated in the Bundesrat, which could dissolve the Reichstag and declare war. The Bundesrat was effectively controlled by Prussia, which could block any measures deemed harmful to its own interests.

Germany under Bismarck

In reality the system was ruled by one man, who was responsible only to the Emperor. The complicated constitutional system depended solely on the personality of Bismarck, who dominated the government and administration by holding the key positions of Chancellor and Prussian Prime Minister. No firm parliamentary principle was established, such as a government responsible to a sovereign parliament—rather the situation was one of ‘government of the parties’, a system that was dubbed ‘Chancellor dictatorship’. Whereas a democratic, constitutional nation state under the principle of sovereignty of the people had been the aim in 1848, the Empire of 1871 was a nationalist authoritarian monarchy.

The Empire was also incomplete with regard to the social and political demands of the middle-class emancipation movement. Claims that the new state should adapt itself to the evolving industrial society were not met, nor was the demand that the nation should have an active role to play in the political process. The Empire did not aim to make changes, but aimed rather to preserve the old Prussian social order that had been reinforced by the dominant position of the Junkers. The opposition parties—the left-wing liberal Progress Party, the Social Democrats and the Catholic Centre Party—were denounced as enemies of the Reich. The first decade of the Reich was filled with high social and party political tensions.

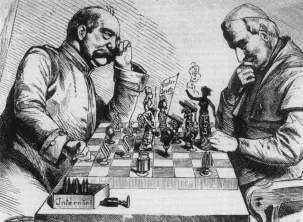

1.1 ‘Between Berlin and Rome’, a cartoon of 1875 (see p. 3)

Document 1.1, a satirical cartoon of 1875, implies ‘a real mix up’, and is critical of Bismarck’s Kulturkampf (cultural struggle)— his attempts to undermine the influence of the Catholic Church in German domestic politics. The cartoon was published in the liberal Ullstein press, which retained an ambivalent attitude towards Bismarck’s policies, but continued to satirise him. There is a need first of all to identify the two protagonists and to understand why they should be engaged in a game of chess. Why did Bismarck wish to weaken the Catholic Centre Party and restrict the power and influence of Catholics and the Papacy in Germanpolitics? Note also the strange characters on the chessboard. Who do they represent and does there appear to be a winner? It has been suggested that the scope of the Kulturkampf was inadequately defined; it took on the nature of a campaign against the Church rather than against the Catholic Party. The cartoon apparently sees the conflict as one between Bismarck and the Papacy, for there is little evidence of the Catholic Centre Party in the cartoon. How far does visual evidence such as a cartoon enhance our understanding of the complexity of historical issues? A cartoon after all, if it is to be effective, needs to make an immediate impression and invariably relies on simplifying issues and events.

Source: Ullstein’s Weltgeschichte, Berlin, 1907–9, Bildarchiv Preussischer Kulturbesitz, Berlin

Does this undermine its importance as an historical source, or should historians take such evidence seriously?

Bismarck’s Kulturkampf turned out to be one of the major failures of his career. The Pope declared anti-Catholic laws null and void and forbade Roman Catholics to obey them. Indeed, the influence of the Catholic Centre Party increased rather than diminished during this period, as did its representation in the Reichstag. Bismarck quickly turned his attention to the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and socialist ideas, which were now seen together as the chief internal threat to his domestic policies.

The Anti-Socialist Law of 1878, Document 1.2, was eventually passed with a comfortable parliamentary majority after an election was fought on the issue. How do you explain this and what events had occurred in 1878 to prompt this Draconian legislation? The document stated that the ‘aims of social democracy’ constituted a ‘danger to the public’. All meetings and publications associated with socialist ideas were banned under this vague pronouncement. Trade unions were also declared illegal. Nevertheless, the law did not prohibit the candidature and election of socialists to the Reichstag. Since it is an ‘official’ Government document, one needs to go beyond the clinical language used here and ‘read between the lines’ for clues to government thinking. Although such documents do not make for exciting reading, they nevertheless constitute an important source for historians, in that they provide evidence of ‘official’ thinking on a particular topic. In this instance, do you find it revealing that there is a lack of detailed information substantiating this legislation?

1.2 The Anti-Socialist Law, 21 October 1878

Content: Law against the aims of Social Democracy of danger to the public.

(NO. 1271) LAW AGAINST THE AIMS OF SOCIAL DEMOCRACY OF DANGER TO THE PUBLIC. 21 OCTOBER 1878.

We, William, German Emperor and King of Prussia by the grace of God decree in the name of the Reich, with the consent of the Bundesrat and Reichstag, the following:

1. Associations which further social democratic, socialist or communist aims and thus threaten to overthrow the existing state and social-structure, are banned.

The same applies to associations in which social democratic, socialist or communist aims are directed at the overthrow of the existing state or social structure in a manner which threatens peace and harmony amongst the population. The same law on associations applies to alliances of any kind…

9. Meetings in which social-democratic, socialist, or communist tendencies, directed to the destruction of the existing order in State or society, make their appearance are to be dissolved. Such meetings as appear to justify the assumption that they are destined to further such tendencies are to be forbidden. Public festivities and processions are placed under the same restriction…

11. All printed matter, in which social-democrat, socialist, or communist tendencies appear…is to be forbidden. In the case of periodical literature, the prohibition can be extended to any further issue, as soon as a single number has been forbidden under this law…

16. The collection of contributions for the furthering of social-democratic, socialistic, or communistic endeavours…as also the public instigation to the furnishing of such contributions, are to be forbidden by the police…. The money seized [by the police] from forbidden collections, or the equivalent of the same, is to fall to the poor-relief fund of the neighbourhood…

28. For districts and localities in which, because of the above-mentioned agitation, public safety is endangered, the following provisions can be put into effect, for the space of a year at most, by the central police of the State in question, subject to the permission of the Bundesrat.

- That public meetings may only take place with the previous permission of the police; this prohibition does not extend to meetings for an election to the Reichstag or the diet.

- That the distribution of printed matter may not take place in public roads, streets, squares, or other public localities.

- That residence in such districts or localities can be forbidden to all persons from whom danger to the public safety or order is to be feared…

Source: Reichsgesetzblatt, no. 34, 21 October 1878

Perhaps Document 1.3, a lithograph entitled ‘Bismarck deals with the Liberals and the Socialists’, provides a more powerful insight into how contemporaries interpreted such repressive measures. Look at the manner in ...