eBook - ePub

The Kakure Kirishitan of Japan

A Study of Their Development, Beliefs and Rituals to the Present Day

Stephen Turnbull

This is a test

Share book

- 316 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Kakure Kirishitan of Japan

A Study of Their Development, Beliefs and Rituals to the Present Day

Stephen Turnbull

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First major study in English of the Japanese 'hidden' Christians - the Kakure Kirishitan, who chose to remain separate from the Catholic Church when religious toleration was granted in 1873 - and the development of the faith and rituals from the 16th century to the present day.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is The Kakure Kirishitan of Japan an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access The Kakure Kirishitan of Japan by Stephen Turnbull in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Ciencias sociales & Estudios étnicos. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Introduction

The Kakure Kirishitan: their nomenclature and location

The Kakure Kirishitan, (literally the ‘Hidden Christians’), are the descendants of the communities who maintained the Christian faith in Japan as an underground church during the time of persecution, which lasted from about 1614 until 1873, and who then chose not to be reconciled with the newly returned Catholic missionaries. The name is sometimes shortened to ‘Kakure’ (the hidden ones), and for the past century several of these communities have continued a separate and distinctive religious faith, its characteristics reflecting the conditions their ancestors experienced during the period of prohibition. When the decision to stay separate was made the original Kakure also chose to remain secret, but their hidden nature nowadays ranges from complete openness to a secret religion never revealed to outsiders. The Kakure, therefore, share a common inheritance with those Japanese Catholics who can trace their ancestry beyond the return of the European missionaries in the 1860s, through the time of secrecy, and back to the originally evangelized communities of the ‘Christian Century’, the expression commonly given to the period between 1549, when missionaries first arrived in Japan, and 1639, when relations with Catholic Europe were effectively severed. In other words the Kirishitan (the original name given to the converts) went underground, becoming thereby Senpuku Kirishitan (secret Kirishitan) and in the years following their re-emergence a split occurred, communities either joining the Catholic Church, or becoming the separated Kakure Kirishitan.

In this work I reserve the expression ‘Kakure Kirishitan’ for the modern, separated communities who form the subject of the study, and not their secret Christian predecessors. In his pioneering study of the Kakure, published in 1954, Tagita Kōya referred to them as Senpuku Kirishitan, but he remains the only writer to have applied this term to the modern communities. Five years later Furuno Kiyoto was to create the term kirishitanisumu (Kirishitanism) for what he regarded as the communities’ unique syncretism of Christianity and Japanese religion, and used the word to contrast their faith with the Catholicism they had rejected (1959:110f). His book is, however, entitled Kakure Kirishitan, the same title (though written in the phonetic hiragana syllabary) given to both book and community that was to be employed a decade later by Kataoka Yakichi (1967). The development of the term has been discussed by Miyazaki (1992b), who argues that at the time of the decision to remain separate, both sides felt the need to make a clear distinction between them. ‘Kakure Kirishitan’ thus became an appropriate term, because its notion of ‘hiding’ referred back to the kakure-mino, the ‘cloak of invisibility’ of Buddhism and Shinto, which the secret Christians had pulled over themselves for two centuries. It also indicated the need to remain in hiding lest persecution should break out again (1992b:3). There was perhaps also the implication that they were ‘hiding’ from the newly returned missionaries. Yuuki identifies a certain ‘lack of tact in the catechists trying to shepherd them back into the church’ (1994:124).

Miyazaki finds inappropriate Tagita’s use of senpuku for the modern communities, as it does not distinguish the situation existing before the granting of religious freedom in 1873 from the situation subsequent to it. He also suggests that the word kakure should be written not in kanji (Chinese characters) or the phonetic hiragana, but in katakana, the phonetic syllabary used for words of foreign extraction, thereby indicating that they are a separate group, and playing down any possible literal interpretation of the meaning as people actually ‘in hiding’ (1992b:4).

We must not, however, overlook the second term ‘Kirishitan’. The modern expression for Christianity is Kirisuto-kyō, ‘Kirishitan’ being used solely for the period prior to 1873. The significance of using ‘Kirishitan’ for the present-day Kakure communities is surely that of looking back to, and identifying with an earlier period of history. Thus one expression used by certain of the communities to describe themselves is Kyū Kirishitan (Old Kirishitan), ‘old’ in this context indicating ‘the original and genuine’, suggesting an explicit link to the faith received during the ‘Christian Century’. However, many Kakure Kirishitan nowadays prefer to dispense with the second term ‘Kirishitan’, and refer to themselves simply as ‘Kakure’, which might indicate a different self-perception, whereby they are not referring to a religious faith at all, but making a statement about their socio-historical identity (Whelan 1994:91).

There are several ways in which the term Kakure Kirishitan has been translated into languages other than Japanese. To use the popular and literal English translation ‘Hidden Christians’ immediately poses the question as to what these people are now hiding from, so it is perhaps preferable that the words should be left in romanized Japanese, thus implying the study of a particular religious group rather than a behaviour pattern. This is the form that will be adopted here. Notwithstanding its usefulness in popular expression, the English term ‘Hidden Christians’ has also had to compete with the use of such expressions as ‘Crypto-Christians’ or ‘Crypto-Catholics’, (e.g. Laures 1954; Schütte 1968; Yuuki 1994).1 As to the terminology applied to the underground church of the time of persecution, Senpuku Kirishitan is favoured by Miyazaki, and in English ‘secret Christians’, ‘underground Christians’ or ‘the underground church’ are all acceptable as a means of identification. But where the historical context is clearly that of the time prior to the 1860s, when the distinction caused by the split had not yet arisen, a simple reference to them as ‘Christians’ or ‘Catholics’ will suffice in the pages which follow.

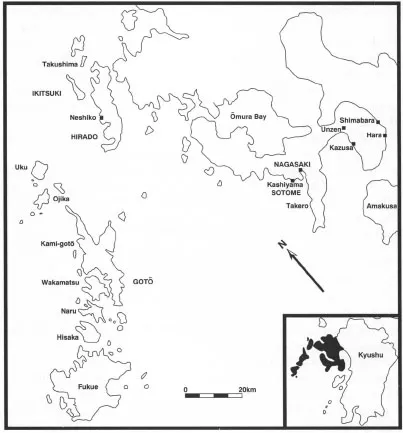

The Kakure Kirishitan communities are located in Nagasaki Prefecture, which lies at the north-west of the main southern island of Kyūshū.2 Its topography is a complex one of islands, peninsulas and enclosed bays, linked in modern times by a number of strategic bridges and coastal roads which have greatly improved communications compared with a century ago. However, during the period of persecution, communications between districts and communities were limited less by geography than by politics, the most formidable barriers being those set up on the borders of the han, the territories of the daimyō, who were the Japanese equivalent of feudal lords. The daimyō ruled the han as the local half of the Tokugawa administrative system known as the baku-han, whereby government was divided between the locally focussed han and the central bakufu (the Tokugawa Shogunate).

The modern administrative area of Nagasaki Prefecture is roughly coterminous with the former province of Hizen, of which the territory was divided between the fiefs of the Matsuura family (the Hirado-han), the Ōmura (the Ōmura-han), the Nabeshima (the Saga-han, plus some other territories), the Matsudaira (the Shimabara-han), the Gotō (the Gotō-han on the island chain of the same name), the Karatsu-han of the Ogasawara, which is now within Saga Prefecture, and the city of Nagasaki, which was under direct government control. The fiefs were by no means tidily divided one from another, and in some cases formed a patchwork of ownership, a particular example being the important Christian site of Kashiyama on the Sonogi peninsula to the north-west of Nagasaki City. Kashiyama is itself a peninsula that projects due south, and achieved great symbolic value to the underground church as it was regarded as pointing towards Rome (Urakawa 1926:306). During the Tokugawa Period it included two villages, Nishi-Kashiyama and Higashi-Kashiyama (west- and east- respectively) located 500 m apart on opposite sides of the valley. Nishi-Kashiyama was however in the Ōmura-han, while Higashi-Kashiyama was in the Saga-han, and was administered from Fukabori, across Nagasaki Bay (Tagita 1954:2, 60). According to Furuno, its location under the daimyō of Saga meant that the Christians of Higashi-Kashiyama suffered less interference than did Nishi-Kashiyama (1959:176).

Figure 1 Nagasaki prefecture and the location of the Kakure Kirishitan

The Kakure Kirishitan communities may be divided into two broad groupings depending on the central focus of their religious lives (Tagita 1954:7). In the north-west of Nagasaki prefecture are to be found the communities who emphasise the preservation and use of certain holy objects, traditionally known as nandogami (the gods of the storeroom), an expression sometimes used for the believers themselves. During the time of persecution this territory was the Hirado-han, under the prominent family of Matsuura. There is a Kakure Kirishitan community at Neshiko, on the west coast of Hirado island, which is an important site of Christian martyrdom, but its inhabitants still maintain their privacy and are unwilling to discuss their faith with outsiders.

By contrast, the island of Ikitsuki, which since July 1991 has been joined to Hirado by a suspension bridge, contains several Kakure communities which display varying degrees of both openness and vigour, and have thus provided data for the main part of this study. The island measures about 10 km north to south, and is about 3 km wide at its southern end, with a narrow neck of land containing the small fishing port of Misaki at its northern tip. The centres of population, which, in the 1965 census consisted of 9650 individuals spread among 2453 households (Miyazaki 1988b:13), are located completely on its eastern, Hirado side, as were the only roads until the building of the circular coastal road that was opened in March 1993. In addition to the port of Misaki, the fishing industry, which is vital to Ikitsuki, is concentrated on the two major modernized ports of Ichibu and Tachiura. Deep sea trawlers now leave from Ikitsuki along with the inshore boats for squid and other varieties. A century ago a whaling fleet was based at Ichibu, but this has long since disappeared. From the sea coast the ground rises steeply through carefully cultivated terraced fields which grow rice and also provide pasture for cattle. The agricultural areas, where nearly all the Kakure are to be found, are from north to south Ichibu-zai, Sakaime, Motofure and Yamada. The farmland finishes in a long backbone of wooded hills of which the peak is the mountain called Bandake (286m), from which almost the entire coast of the island is visible. To the west there is a steep descent through forest to the open sea, while in the east lies the shoreline of Hirado, and before it the prominent landmark of the small rocky ‘martyrs’ island’ of Nakae no shima, where several Christians were executed in 1622 and 1624.

The other broad division of Kakure is characterized by the communities’ commitment to the church calendar (Tagita 1954:7).3 Almost all these groups fall within what was formerly the Ōmura-han, of which the most important are those associated with the Sotome area, on the western side of the Sonogi peninsula which divides Ōmura Bay from the sea to the north-west of Nagasaki city. Most of the Sotome area is now in the administrative district known as Sotome-chō (township), although the above-mentioned Kashiyama falls within the borders of Nagasaki City. Sotome-chō contains villages such as Kurosaki, Shitsu and Nagata, all of which are associated with an underground Christian tradition, and have Kakure communities in various states of secrecy, vigour or decline.

The Kakure communities of the Gotō island chain are commonly believed to have originated from the Sonogi peninsula, rather than from surviving Gotō Christians, although this theory has recently been challenged.4 Many families did move there from the Sonogi peninsula at the end of the eighteenth century, taking their secret Christian faith with them. They fled poverty more than persecution, their emigration being part of an arrangement between the Ōmura daimyō, whose lands had an excess of population, and the Gotō daimyō who had a shortage of labour, in a process described by Whelan (1992:382). The Gotō Kakure are to be found nowadays on Fukue, the southernmost island of the Gotō group, and Naru. The Kakure population of Takero, a village on the Nomo peninsula south of Nagasaki also came about as a result of emigration from the Sotome area (Kataoka 1986:177). Finally, there are within this group the Kakure of Nagasaki City. The Christians from Urakami in Nagasaki were the first to be revealed to the returning missionaries, and most rejoined the church, leaving very few to stay as Kakure Kirishitan. This, together with the depredations caused by the Atomic Bomb, has left little in the way of a Kakure tradition today. A small community was still in existence in Ieno-machi in 1993, though Miyazaki, who has studied them, reports their rituals as being confined to family ancestor worship using Christian prayers, with any other recognisable Kakure Kirishitan element being virtually extinct (1986:177).

The one factor that all the Kakure Kirishitan would appear to have in common is a decline both in numbers and in activity. According to Yuuki, it is many years since any baptisms were performed in Takero, Sotome or the Gotō.5 Instead, they have become communities whose average ages are growing as their numbers fall. Out of all the Kakure groups it is those on Ikitsuki that are least in decline, but even there a fall in numbers may be noted.6

Aims of the study

It is the overall aim of the present work to identify the influences which have led to the creation, preservation, development and expression of the Kakure Kirishitan faith. As all the Kakure communities are in decline, a secondary aim is that of recording even a small amount of a unique corpus of belief and ritual before it is lost forever, and linking it to the remarkable achievement of their senpuku predecessors. Within these broad aims are contained five basic questions:

(1) What relationship exists between the input of Christian doctrine and ritual in the sixteenth century, the religious life of the underground church, and the Kakure Kirishitan faith of today?

(2) What relationship exists between Japanese religion and the Kakure Kirishitan faith?

(3) What other social, political, religious or historical influences have been involved in the development and current expression of the Kakure Kirishitan faith?

(4) Are there differences between various Kakure communities, and, if so, do they provide an explanation of why some have continued while others have died out?

(5) Should the Kakure Kirishitan faith be regarded as the preservation of Christianity, the transformation of Christianity, or the denial of Christianity? Can any positive contribution to Christianity be identified?

To assist the investigation, I suggest three broad theoretical models of the process that may have taken place in the creation of the Kakure faith. It must however be noted at this stage that, as suggested by question (4) above, different models may apply to different communities, and there may also have been some variation within the same communities over a period of time.

The first model is that of the Kakure faith as the preservation of an old form of Catholicism that has been modified by its surroundings. According to this model Kakure prayers and rituals, for example, may be seen as a form of time capsule linking us to the originally evangelised Kirishitan, with whom there is a close identification, and to whom the forms of worship may be traced. In a note on the Kakure in his study of Japanese folk religion, Hori wrote that ‘they still believe they transmit the authentic Catholicism of Xavier’, even though, in Hori‘s opinion, ‘the contents of their faith have been radically transformed and reshaped by folk religion and indigenous elements’ (1968:15). The possibility will be considered that the supposed ‘unusual form of Catholicism’ exhibited by the Kakure may have come about as a reaction to the deprivation of the Church’s sacraments, caused directly by the Japanese Christians’ isolation. In the absence of priests there could not have been any Eucharist or confession, anointing of the sick, confirmation or holy orders, resulting in a religious system that can best be understood as a response to this loss. The sacraments may then have been compensated for during the time of secrecy by identifiable alternative practices, and perhaps by a greater emphasis on the more popular and less sacramental aspects of Catholic devotion. All these characteristics should therefore appear among Kakure practices, with the resultant faith regarded as the preservation of Christianity.

By contrast, the second model identifies a radical transformation of Catholicism, rather than any preservation of it, which came about as the result of an active and willing decision either to camouflage Christian belief and ritual in a cloak of Buddhism, Shinto and folk religion, or simply to express it through these forms. This camouflage or expression, unavoidably, then became a form of syncretism, a term defined below. By deliberately choosing certain elements of Japanese religion, and deliberately discarding other elements of Catholicism, the Kakure have therefore produced an identifiably Christian yet syncretic faith, which may be regarded as a unique contribution to Christianity. From this point of view the Kakure Kirishitan represent the acculturation of Christianity within the Japanese religious milieu. No surprise is expressed at this metamorphosis, for it is the same process that made Japanese Buddhism Japanese, and the result is regarded as evidence that Christianity can be subject to a similar change. Christianity is therefore preserved, but transformed.

The third model takes a somewhat similar view of the process of transformation, but rejects the idea that a uniquely Japanese Christian faith was produced. In this view, the Kakure have totally abandoned Christianity. They are therefore the adherents of a new religion, akin to the other ‘New Religions’ found in Japanese society, some of which involve borrowed Christian elements. The Kakure faith was therefore brought about by a blending of indigenous traditions with a str...