![]()

![]()

I

The Great Glen

This great opening is called by the generall name of Glenmore [Gleann Mòr]. The extremitys of these mountains gradwally declyning from their several summitts, open into glens or outlets, where yow have various views of woods, rivers, plains, and laiks, and the torrents, or falls of water, which every here and there tumble down the presipices, and, in many places, seem to breck through the cliffs and cracks of the rocks, strick the eye more agreeably than the most curious artificiall cascades.

In a word, the number, extent, and variety of the several prospects; the verdure of the trees, shrubs, and greens; the odd wildness of the hills, rocks, and precipeces; with the noise of the rivoletts and torrents, brecking and foaming among the stones, in such a diversity of collowrs and figures; the shineing smoothness of the seas and laiks, the rapidity and rumling of the rivers falling from shelve to shelve, and forceing their streams through a multitude of obstructions, have something so charmingly wild and romantick as even exceeds discription.

John Drummond of Balhaldy

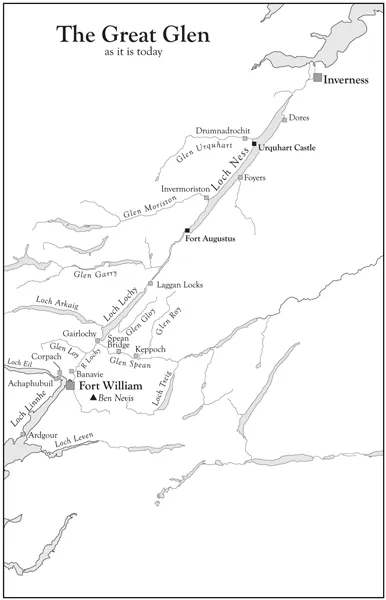

IF THE TSAR of all the Russias had drawn a line on the map with a ruler from Inverness to Fort William to show where a new railway was to run, as we are told Tsars were wont to do, it could hardly have been straighter than Gleann Mòr (the Great Glen). It is a glen formed not by the action of water seeking its way forward along the easiest path, but by the movement of the earth’s crust ruthlessly splitting rocks asunder along a fault line. It was formed nearly 400 million years ago by a colossal upheaval during which the most northerly part of the land mass was sheared and pulled away roughly 65 miles towards the south-west. The wide and relatively flat bottom of the glen was then carved out by glaciers during the Ice Age, but rock movement is not yet complete and many earthquakes are still recorded, most of them, fortunately, only very small ones.

After the Ice Age the glaciers melted – their progress is charted by the parallel ‘roads’ of Glen Roy – leaving what eventually became a series of lochs with the rivers that drain and feed them, the whole creating an almost continuous watery boundary between this furthest section of what is now Scotland – the last slice we might term it – and the rest of Great Britain. It is rather as though a giant had placed his right hand on the major land mass and torn the top portion away with his left hand and had then, instead of discarding it, put it back, but out of alignment. It is still grinding its way south-westwards.

As the Ice Age receded the earth warmed up and plant life began to appear. The monocultures of spruce with their tightly packed trees and dark, barren forest floors, which cover many of the hills today, were mercifully absent until the last century, but the magnificent Scots pines, which can reach 50 to 70 feet in height, early began to clothe the slopes of the glen, followed by the Druids’ sacred tree, the oak, and by other species such as birch, willow and alder. Smaller bushes – bog myrtle and juniper – pushed up and fragile flowers began to spread over the floor of the glen. Then came the animals – reindeer, lynx and brown bear, probably all gone by the tenth century. Wild boar and beaver persisted for longer. Deer too were there but perhaps in smaller numbers than today because of the presence of wolves which did not die out until the 18th century, the last having been killed, it is said, in 1743.

The modern motorist might well be forgiven for thinking the glen far from straight as he weaves his way round interminable twists and bends to avoid outcrops of rock or invasive loch or river, but there are places where he is bound to acknowledge its straightness; at the foot of Loch Ness, for instance, where that great water stretches away to the north, further than the eye can see; or at the slope by Aberchalder where the four miles of Loch Oich and the dry land which separates it from Loch Lochy and, on a clear day, Loch Lochy itself are laid out before him, while from somewhere south of Corriegour beside Loch Lochy there is another straight vista down to the hills opposite Fort William and to the Ardgour hills fringing the Firth of Lorne.

The water levels in the lochs and rivers have altered down the centuries and we can only guess what they were at any particular time. These levels have been influenced recently by the dams built to supply electricity, but before then they were subject only to natural processes, to rainfall and rock movements and the unceasing force of the wind.

The glen is bounded on either side by great hills, in the south including Ben Nevis, the greatest of them all. In winter there are wide snowfields on the slopes of these hills and even in midsummer patches of snow remain on the northern faces. A fall of snow shows up every undulation, every rock, every hollow which the softer days of spring and summer hide in clouds of heather and deer grass.

In fierce winds the lochs turn grey and fringe their tossed waves with spumes of white. On still, damp days they pull down thick mists and hide beneath them, drawing the shining birches and the dark heather into their fitful whiteness to wait, unseen or partly seen, until the sun breaks through. Sometimes the lochs are still and, like giant looking-glasses, hold the trees and the hills in a spell beneath their waters.

Ptolemy (Claudius Ptolemaeus), the astronomer and geographer who lived from 90-168AD recognised the Caledones, who lived along the Great Glen, as the dominant tribe in the north of Scotland, whereas the Romans gave the name of Caledonia to the whole area which, from their point of view, was inhabited by totally barbarous tribes. These ‘barbarous tribes’ came to be known as Picts – Latin ‘picti’ (painted people) – perhaps from their delight in painting their bodies, which they may well have done to frighten their enemies and not merely as a decoration, though whether they were as highly decorated as some illustrations suggest we may never know.

One might think that the Great Glen must have been welcome as a highway for travellers from the broken rock-strewn coastline of the south-west to the cold waters of the North Sea, from the fertile plains of Moray to Moluag’s blessed isle of Lismore, yet a look at the many maps plotting the presence of, for instance, Pictish monuments and archeological sites, thanes, nunneries and monasteries, would suggest that not very much was going on there in the early Christian period although plenty of Bronze Age remains have been uncovered. There was little good agricultural land and most of the glen was, of course, a long way from the sea, which was the favoured medium for the transport of people and goods until the last two hundred years or so. As journeys through this glen must have involved fighting one’s way over hills and rocks and negotiating lochs, rivers, waterfalls and bogs there may have been little settlement along this apparently favourable route in earlier centuries.

A journey up the Great Glen from the south is generally regarded as beginning at corpach by Fort William where the waters of Loch Eil and Loch Linnhe meet, but I cannot help thinking of the glen as beginning eight miles further south at the Corran Narrows where Upper Loch Linnhe is very nearly enclosed and shut off from the salt tides which rule its lower half. The water rushes strongly through this small gap and the ferry boats crossing to and from Ardgour have to make a detour up the loch and then turn back again into the current, which is too strong for them to make their way straight across. It is here that the traveller from the north first finds himself in or beside the open sea and here that the southerner, if he is travelling by water or on the west bank, has his first clear view of the highest hills. The east bank has the busy road, but on the west bank is a charming, narrow, single-track road leading through the little settlements of Inverscaddle, Goirtean a’ Chladaich, Stronchreggan, Trislaig, Camus nan Gall and so, round the corner into Loch Eil, to Achaphubuil. All the way up the loch this little western road gives wonderful views of Ben Nevis and, it must be confessed, less wonderful ones of Fort William which, for all its advantages of water and mountains, has sadly missed its chance of being an attractive town.

The next ten to 15 miles (16-24km) up the glen from Fort William are dominated by the great mass of Ben Nevis and its companion, Aonach Mor. Ben Nevis, the highest hill in the British Isles, is all the more impressive because it rises from sea level, whereas the next highest hill, Ben MacDhui in the Cairngorms, starts from a base of 1400ft (427m) above sea level. There is snow on Nevis’s north-east face even in the middle of summer. Its peaks and corries are again best appreciated from the west side of the glen or from the relatively flat land of the strath where the river Lochy runs between fields of green grass or of heather and juniper and where we find Tom a’Charich, Brackletter and Highbridge (General Wade’s construction, now broken down and unusable).

Halfway up the slope above Spean Bridge is the church of Kilmonivaig (the largest parish in the Highlands) and at the top of the slope is the Commando Memorial, erected to remember those Commandos who trained in this area during the Second World War. In its elevated position, for the land falls away sharply to the west here, the dark figures on the monument stand out clearly against the paler sky. A few years ago someone, for what reason I cannot remember, wanted to plant trees round it, which would have greatly lessened its impact, but every Commando and ex-Commando in the world wrote in to protest and the site was left as it was. The road divides here, the main branch continuing up the east bank and the other going west over the canal at the foot of Loch Lochy where it meets the road to Achnacarry – Cameron of Lochiel’s stronghold. Here is Bunarkaig where the river Arkaig joins Loch Lochy; the little bridge there looks over the shining water of the bay and the wide sweep of the loch towards the great hills.

On the east bank of the glen the main road passes on the right the huge gash of Glen Gloy going up to join the Corrieyairack Pass and forming part of an ancient highway between west and east. The road moves close to the loch here and sweeps up to Laggan Locks along stretches where great trees rise above occasional white houses and make of the road a green tunnel letting the sunlight or the mist in through their leaves and branches.

Laggan Locks is at the north end of Loch Lochy and the canal takes over here, but only for two miles, when Loch Oich begins. It is only four miles (6.5km) long and on average 350 yards (320m) wide and at its deepest point 133ft (40m) deep, whereas Loch Lochy is ten miles (16km) long and 1050 yards (965m) wide on average, with a mean depth of 229ft (70m). Half way up Loch Oich on the west bank are the ruins of old Invergarry Castle, the seat of the MacDonalds of Glengarry. The River Garry flows in here from the west and the loch continues to Bridge of Oich and Aberchalder, where the canal begins again, running close to the River Oich (it is hard to disentangle them on the map) and between banks of heather to Fort Augustus on the south shore of Loch Ness.

This loch easily eclipses the other two in size, being about 24 miles (38km) long and one mile (1.6km) wide, and its maximum depth is somewhere between 750 and 1000ft (238-305m). It is quite devoid of islands, apart from Cherry Island at the south end near Fort Augustus Abbey. This is not a real island but a crannog, an artificial island, built perhaps as a place of refuge in times of danger; it may be 2500 years old. There were cherry trees on it at one time, perhaps visited by the soldiers at the fort and it is also thought that there was once a mediaeval castle there, but now there is room only for a single pine tree and a few bushes, for the water level of the loch is much higher than it used to be. Somewhere in the surrounding water is a causeway that linked Cherry Island to the west bank. One of the monks at the Abbey, Dom Odo Blundell (fl.1910), went down in an old-style diving suit – one of those vast metal suits roughly following the lines of head and body and with a large glass window at face level – to see how the crannog was constructed and found it to be made of layers of different-sized stones kept in place with logs of wood which will have hardened to an iron-like consistency during their long sojourn in the water.

From Fort Augustus there are two roads to Inverness. The main road follows the west bank of Loch Ness and goes through the small settlement of Invermoriston and the somewhat larger one of Drumnadrochit. Invermoriston is flanked by two massive hills, Sron na Muic (the promontory of the pig) to the south and Craig nan Eun (crag of the birds) to the north, which stand like substantial sentinels at the mouth of Glenmoriston. To the south of Drumnadrochit is the great rounded hill of Meallfuarmhonaidh which dominates the whole of the west bank. The village itself is heralded by the ruins of ancient Castle Urquhart on Strome Point where there has been some kind of fort or castle since the Iron Age. Quite apart from the interest to be found in the castle itself, its position is an excellent one for observing the loch and spotting or not spotting the Monster – first seen, as far as we know, by St Columba in the 6th century. Columba acually saw it in the River Ness and not in the loch, but its habitat seems to have slipped south since then and there is a museum in the village dealing with every known fact, or fiction, about it.

The last settlement before Inverness is Lochend, where a line of houses stands across the top of the loch like a bastion holding back that great sheet of water. Here on the east bank, are the towers and pinnacles of Aldourie Castle, looking, amongst its trees, like something out of a fairy tale.

The east bank of Loch Ness looks rather unexciting from across the water, but this is far from being the case, for there are so many different kinds of landscape to be found there. First, from the Fort Augustus end, there is the road along the south shore of the loch near the former Abbey buildings. Not much more than half of the loch can be seen from here; the rest of it seems to have slipped over the curve of the earth and disappeared. The road strikes away from the water and to the north-east behind a curtain of low hills and through hilly but soft, green agricultural land.

Then comes Loch Tarff with its pretty wooded islands and the long climb up to a viewpoint from which an amazing landscape of lochs is visible – Loch Knockie, Loch Kemp, Loch Mhòr, Loch Ruthven, Loch Duntelchaig, Loch Ashie, and a host of smaller ones. They lie as it were in a lost landscape, hidden from the Great Glen itself yet part of it, sheltered by a line of low hills which have their feet in Ness waters.

Beyond the viewpoint and at a much lower level is Whitebridge, with its Wade bridge and the hotel that was once a kingshouse,1 and then Gorthleck amidst scattered houses overlooking Loch Mhòr. There are charming narrow roads between Errogie, Foyers and Inverfarigaig leading up and down steep hillsides, beside groves of trees and great mossy boulders, always with some little burn below them seeking a path, this way and that, down to the great loch itself.

Round Croachy and Brin there is farm land, dull and flat in itself but enlivened by huge and grotesque rocks like the one at Brin where the curlew still make their bubbling calls. To the west lie all the lochs visible from the viewpoint. Loch Ruthven is the special haunt of birds, watched over by the RSPB. At Loch Ashie ghostly armies have been seen in the sky and the clash of their swords and beating of their drums are heard, but no-one knows in what cause they are fighting. Dores, on the shore of Loch Ness, is nearby and from here there is an impressive view down the loch of Mealfuarmhonaidh on the further side of Urquhart Bay. It is only a few miles now to Inverness.

The River Ness flows out of its loch past the Pictish fort at Torvean (behind the golf course club house), past the islands and the castle at the main bridge and out into the Moray Firth and its leaping dolphins. The islands are full of paths and trees with flowers and bushes in between and places where one can observe the flow of the river and see the towers of St Andrews Cathedral or the roofs of Eden Court Theatre, part of which was once the Palace of the Bishop. It is a great place for walking a dog and for meeting other dogs and the paths wind about and cross little bridges to other islands or to the east bank; there is a big ornamental metal bridge across the river here which bounces up and down as one walks, rather to the surprise of the dog. It is one of three similar bridges, attractive and useful to the pedestrian, who can cross the river without using the main bridge. The river slides on beneath them and beneath two road bridges taking traffic into Inverness. The hills flatten out, the sky widens, the wind blows more strongly, Ben Wyvis spreads herself across the horizon, looking like a film set. We have reached the northern end of the Great Glen.

The following chapters introduce human life into this lovely prospect of plants and flowers, of mountain, loch and river. The people who lived there before the Christian era – the Caledones – had responded to the call of Calgacus and sent their men to join him at Mons Graupius, where he confronted the Roman legions but did not win a victory. Yet the Romans did not settle in the north of Scotland; they established camps in this place and in that and then moved on, leaving those they had called Picts still in possession of their land. Later the Picts intermingled with Irish Gaels heralded by St Columba. It was the Irish tongue that prevailed although how different it was from the (probably Celtic) tongue spoken by the Picts it is impossible to say.

When Calum Cille (St Columba) went up the Great Glen in the sixth century he went to visit the King of the Picts and represented a small colony of Irish settled along the western seaboard of Scotland, roughly where Argyll now is. This colony was to grow to include the western isles and to creep up the Great Glen to the north-east, eventually absorbing the Pictish peoples and creating the Kingdom of the Scots, as the Irish settlers came to be called. We do not actually know whether the Picts melted into the Scots or the Scots into the Picts or indeed exactly when or how this came about. As a famous spoof history book tells us:

The Scots (originally Irish, but by now Scotch) were at this time inhabiting Ireland, having driven the Irish (Picts) out of Scotland; while the Picts (originally Scots) were now Irish (living in brackets) and vice versa. It is essential to keep these distinctions clearly in mind (and verce visa).2

The people and events described in the following pages, starting with Columba, are scattered very intermit...