eBook - ePub

Manteo's World

Native American Life in Carolina's Sound Country before and after the Lost Colony

- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Manteo's World

Native American Life in Carolina's Sound Country before and after the Lost Colony

About this book

Roanoke. Manteo. Wanchese. Chicamacomico. These place names along today’s Outer Banks are a testament to the Indigenous communities that thrived for generations along the Carolina coast. Though most sources for understanding these communities were written by European settlers who began to arrive in the late sixteenth century, those sources nevertheless offer a fascinating record of the region’s Algonquian-speaking people. Here, drawing on decades of experience researching the ethnohistory of the coastal mid-Atlantic, Helen Rountree reconstructs the Indigenous world the Roanoke colonists encountered in the 1580s. Blending authoritative research with accessible narrative, Rountree reveals in rich detail the social, political, and religious lives of Native Americans before European colonization. Then narrating the story of the famed Lost Colony from the Indigenous vantage point, Rountree reconstructs what it may have been like for both sides as stranded English settlers sought to merge with existing local communities. Finally, drawing on the work of other scholars, Rountree brings the story of the Native people forward as far as possible toward the present.

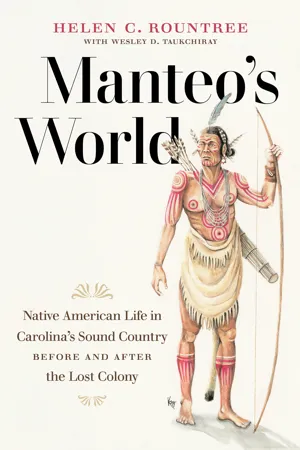

Featuring maps and original illustrations, Rountree offers a much needed introduction to the history and culture of the region’s Native American people before, during, and after the founding of the Roanoke colony.

Featuring maps and original illustrations, Rountree offers a much needed introduction to the history and culture of the region’s Native American people before, during, and after the founding of the Roanoke colony.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Manteo's World by Helen C. Rountree,Wesley D. Taukchiray,Helen Rountree in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & North American History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I | The Indian World, 1583

CHAPTER ONE

The Land and the Waters

The people native to the Carolina Sounds region inhabited a natural world of interlaced land and waters, much of the land being wetlands that did not seem like land at all. In this world they lived by hunting, fishing, foraging for plants, and farming, all of which required them to know exactly what they were doing in order to survive. Over many millennia they had learned to cope expertly. But any Europeans who became stranded there were in danger of starving, unless they could tap the locals’ knowledge.

The territory of the North Carolina Algonquian speakers stretched between approximately 35 degrees and 36 degrees 35 minutes north latitude and 75 degrees 27 minutes and 77 degrees west longitude. That is the area from the Atlantic Ocean over to the Suffolk Scarp that runs past the west end of Albemarle Sound and then up the Chowan River, with Indian lands being on both sides; and from roughly the North Carolina–Virginia line southward to the Pamlico River, again with Indian lands being on both sides. It is a region of broad sounds and wide estuaries, with generally low-lying lands around them.

The climate is one of cool, humid winters and hot, humid summers. The Appalachian Mountain barrier to the west, as well as the area’s latitude, means that winter cold fronts often bypass it, hitting New York and New England instead with heavy snowfall. The Gulf Stream that passes by North America’s east coast makes its nearest approach off Cape Hatteras, contributing further warmth. Thus northeastern North Carolina sees snow only infrequently, and then it does not last long on the ground.

Those winter storms usually approach from the northwest, though some genuine northeasters do occur in the wintertime. But in summer it is different. Storm tracks usually come from the southwest, after deluging the Gulf Coast, while less frequent ones take the form of hurricanes making their way northward from the Caribbean or swinging in from the Atlantic. North Carolina, with its coastline protruding so far eastward, is a major target for hurricanes, exceeded only by Florida, Texas, and Louisiana in the number of “hits” in the past century. That would have held true for the late 1500s, too, as the English would-be colonists found out.

The climate in general, however, was somewhat colder back then, in terms of average annual temperature, because the Little Ice Age (ca. 1550–1800) was in progress. It affected mainly the northern hemisphere, and what lowered the annual average temperature by one and a half to two degrees Celsius (up to three and a half degrees Fahrenheit) was the tendency toward considerably colder winters.1 Written records in the Carolina Sounds region are lacking, but literate eyewitnesses at Jamestown two decades later wrote of obstructing ice in the James and York Rivers, something that is rare nowadays.

Longer, colder winters shrank the growing season for crops, though at the territory’s southerly latitude and low altitude it would have made little difference to Native American farmers. Another factor, however, did affect their crop year: droughts. The Mid-Atlantic region suffers a drought roughly one in every three or four summers. Multiple-year droughts are not common, but tree-ring studies have shown that a major drought occurred in 1587–89.2 It would not have affected people during the first two English visits (1584, 1585–86), but it must have made real difficulties for Indians and English alike, beginning in that winter of 1587–88.

The Algonquian speakers’ lands lay mainly on the outer coastal plain, though the Chowanokes’ foraging territory extended some distance into the inner coastal plain. In that westerly area the land rolls gently, cut through by small streams and transected by old beachfronts like the three-million-year-old Suffolk (or Pamlico-Chowan) Scarp. East of it, the terrain is flat and often poorly drained. The soil is sandy, and the land consists of low-lying, often marshy peninsulas cut by sluggish rivers (or more properly, estuaries), with broad, open sounds to the east (map 1.1).3 Wetlands can be good foraging territory, but they are not amenable to farming.

The Carolina Sounds are extensive, shallow estuaries mostly closed off from the Atlantic Ocean by narrow barrier islands that are punctuated by inlets, some relatively permanent (e.g., Hatteras Inlet), some fairly long-term (e.g., Oregon Inlet, formed by a hurricane in 1846), and some quite temporary (e.g., the inlet that keeps trying to form just north of Cape Hatteras).4 Therefore the waters in the Sounds range from salty-brackish near inlets to oligohaline (slightly salty) farther away, to fresh still farther away in Albemarle Sound, northern Currituck Sound, and up the tributary rivers (map 1.2). Variations in the waterways’ salinity make for considerable variations in plants and animals living in them, including those species useful to people.

MAP 1.1 Wetlands (tidal flats, marsh, swamp) in the Carolina Sounds region, shown in gray.

A map of the salinities in the 1580s would differ, however, from the map of today’s, especially in the Albemarle Sound. And understanding the resources available to Indian people of that time requires us to try to reconstruct what things were like in their day, not ours. In a nutshell, in the Albemarle Sound, the salty-brackish waters extended somewhat farther westward from the barrier islands than they do today, in spite of the modern rise in sea level. There are at least two good reasons for this situation.

MAP 1.2 Inlets in the Outer Banks and resulting modern salinities in the Carolina Sounds and their tributaries. Salinities run from ocean saltiness (white) through salty-brackish (light gray) and fresh-brackish (darker gray) to fresh (black).

First of all, the layout of inlets was somewhat different from today’s, when the sandbank barrier stretches continuously from Virginia Beach, Virginia, to Cape Hatteras with only one breach: Oregon Inlet. In the 1580s, that barrier across the east end of Albemarle Sound had four breaches: Old Currituck Inlet (pre-1585 to 1731), near the present-day North Carolina–Virginia line; Trinity Harbour Inlet (pre-1585 to mid-1600s), several miles north of the modern Currituck–Dare County line; Roanoke Inlet (pre-1585 to 1811), near the eastern end of the U.S. 64/264 connector between the Outer Banks and central Roanoke Island; and Gunt Inlet (pre-1585 to 1798), just north of modern Oregon Inlet. These four openings made southern Currituck Sound, eastern Albemarle Sound, and Roanoke and Croatan Sounds saltier than they are today, and they would have contributed more seawater yet at high tides and during storms to the central and western Albemarle Sound than Oregon Inlet can do today by itself.5 Thus the progression of salty to freshwater salinities would have lain farther west in the sound, and higher up the tributaries, than it does today. That in turn would have affected which shellfish (oysters, clams, and the like) were available in which locations to people wanting to eat them.

Secondly, the amount of rain runoff into the waterways differed four centuries ago, though to a lesser extent than in the Chesapeake Bay, where there are fewer huge wetland areas and more large cities and vacation houses along the waterfront. Modern building by humans covers land with hard, impenetrable surfaces: roofs, paving, and so on. Not only that, but the human population of the Sounds region today is much, much larger than it was in the 1580s. Back then, most of the rain that fell over land was absorbed by the forest-covered land itself and did not run off into the waterways. Therefore, as in the Chesapeake Bay region, less rainwater was reaching the waterways, resulting in higher salinities reaching farther upstream than today’s. The upshot, for people living partly by fishing and shellfishing, was that oyster grounds were found farther west in Albemarle Sound, farther north in Currituck Sound, and farther up all of the sounds’ tributary rivers than they are today. And people had to go farther still upstream to find big cypress trees for canoes (or else trade for them).

Even though the region’s land does not vary all that much by altitude, and the rivers and sounds are all relatively shallow, there is a wealth of different habitats for plants and animals to live in. Waterways vary not only in salinity and depth but also in the types of bottom they have: mud, sand, or a combination thereof in the coastal plain. Even low-lying lands vary in the composition of their soils and thus in the plants their soils will support, aside from the matter of drainage. The animals feeding on the plants vary in turn.

Northeastern North Carolina has several types of tree cover. Most of the forest on the dryer lands, with their sandy soils, used to be a Southern mixed pine forest, the dominant species being longleaf pine (Pinus palustris), which needs forest fires at intervals in order to reproduce. Since deer like to feed on the grasses that grow after a fire, the Native people were known to start forest fires in order to attract deer to those localities later. The trees grow tall and straight, and they were logged almost out of existence after the arrival of the English; only a few small pockets of that kind of original forest remain. The dominant pines today, given modern fire-prevention tec...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Preface

- Introduction

- Part I | The Indian World, 1583

- Part II | A More Complicated, Faster-Moving World

- Afterword

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Index