- 496 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Introduction to World Religions

About this book

A leading textbook for world religion, this new edition is designed to help students in their study and research of the world's religious traditions. Known and valued for its balanced approach and its respected board of consulting editors, this text addresses ways to study religion, provides broad coverage of diverse religions, and offers an arresting layout with rich illustrations.

The second edition has new and extended primary source readings, a stronger section on the Religions of South Asia, additional maps, a new full-color, student-friendly format, and more.

The second edition has new and extended primary source readings, a stronger section on the Religions of South Asia, additional maps, a new full-color, student-friendly format, and more.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

Understanding Religion

Summary

Belief in something that exists beyond or outside our understanding – whether spirits, gods, or simply a particular order to the world – has been present at every stage in the development of human society, and has been a major factor in shaping much of that development. Unsurprisingly, many have devoted themselves to the study of religion, whether to understand a particular set of beliefs, or to explain why humans seem instinctively drawn to religion. While biologists, for example, may seek to understand what purpose religion served in our evolutionary descent, we are concerned here with the beliefs, rituals, and speculation about existence that we – with some reservation – call religion.

The question of what ‘religion’ actually is is more fraught than might be expected. Problems can arise when we try to define the boundaries between religion and philosophy when speculation about existence is involved, or between religion and politics when moral teaching or social structure are at issue. In particular, once we depart from looking at the traditions of the West, many contend that such apparently obvious distinctions should not be applied automatically.

While there have always been people interested in the religious traditions of others, such ‘comparative’ approaches are surprisingly new. Theology faculties are among the oldest in European universities, but, while the systematic internal exploration of a religion provides considerable insights, many scholars insisted that the examination of religions more generally should be conducted instead by objective observers. This phenomenological approach was central to the establishment of the study of religion as a discipline in its own right. Others, concerned with the nature of society, or the workings of the human mind, for example, were inevitably drawn to the study of religion to expand their respective areas. More recently, many have attempted to utilise the work of these disparate approaches. In particular, many now suggest that – because no student can ever be entirely objective – theological studies are valuable because of their ability to define a religion in its own terms: by engaging with this alongside other, more detached, approaches, a student may gain a more accurate view of a particular religion.

chapter 1

What is Religion?

Although no one is certain of the word’s origins, we know that ‘religion’ derives from Latin, and that languages influenced by Latin have equivalents to the English word ‘religion’. In Germany, the systematic study of religion is known as Religionswissenschaft, and in France as les sciences religieuses. Although the ancient words to which we trace ‘religion’ have nothing to do with today’s meanings – it may have come from the Latin word that meant to tie something tightly (religare) – it is today commonly used to refer to those beliefs, behaviours, and social institutions which have something to do with speculations on any, and all, of the following: the origin, end, and significance of the universe; what happens after death; the existence and wishes of powerful, non-human beings such as spirits, ancestors, angels, demons, and gods; and the manner in which all of this shapes human behaviour.

Because each of these makes reference to an invisible (that is, non-empirical) world that somehow lies outside of, or beyond, human history, the things we name as ‘religious’ are commonly thought to be opposed to those institutions which we label as ‘political’. In the West today we generally operate under the assumption that, whereas religion is a matter of personal belief that can never be settled by rational debate, such things as politics are observable, public, and thus open to rational debate.

The essence of ‘religion’

Although this commonsense distinction between private and public, sentiment and action, is itself a historical development – it is around the seventeenth century that we first see evidence that words that once referred to one’s behaviour, public standing, and social rank (such as piety and reverence) became sentimentalized as matters of private feeling – today the assumption that religion involves an inner core of belief that is somehow expressed publicly in ritual is so widespread that to question it appears counterintuitive. It is just this assumption that inspires a number of people who, collectively, we could term ‘essentialists’. They are ‘essentialists’ because they maintain that ‘religion’ names the outward behaviours that are inspired by the inner thing they call ‘faith’. Hence, one can imagine someone saying, ‘I’m not religious, but I’m spiritual.’ Implicit here is the assumption that the institutions associated with religions – hierarchies, regulations, rituals, and so on – are merely secondary and inessential; the important thing is the inner faith, the inner ‘essence’ of religion. Although the essence of religion – the thing without which someone is thought to be non-religious – is known by various names (faith, belief, the Sacred, the Holy, and so on), essentialists are in general agreement that the essence of religion is real and non-empirical (that is, it cannot itself be seen, heard, touched, and so on); it defies study and must be experienced first-hand.

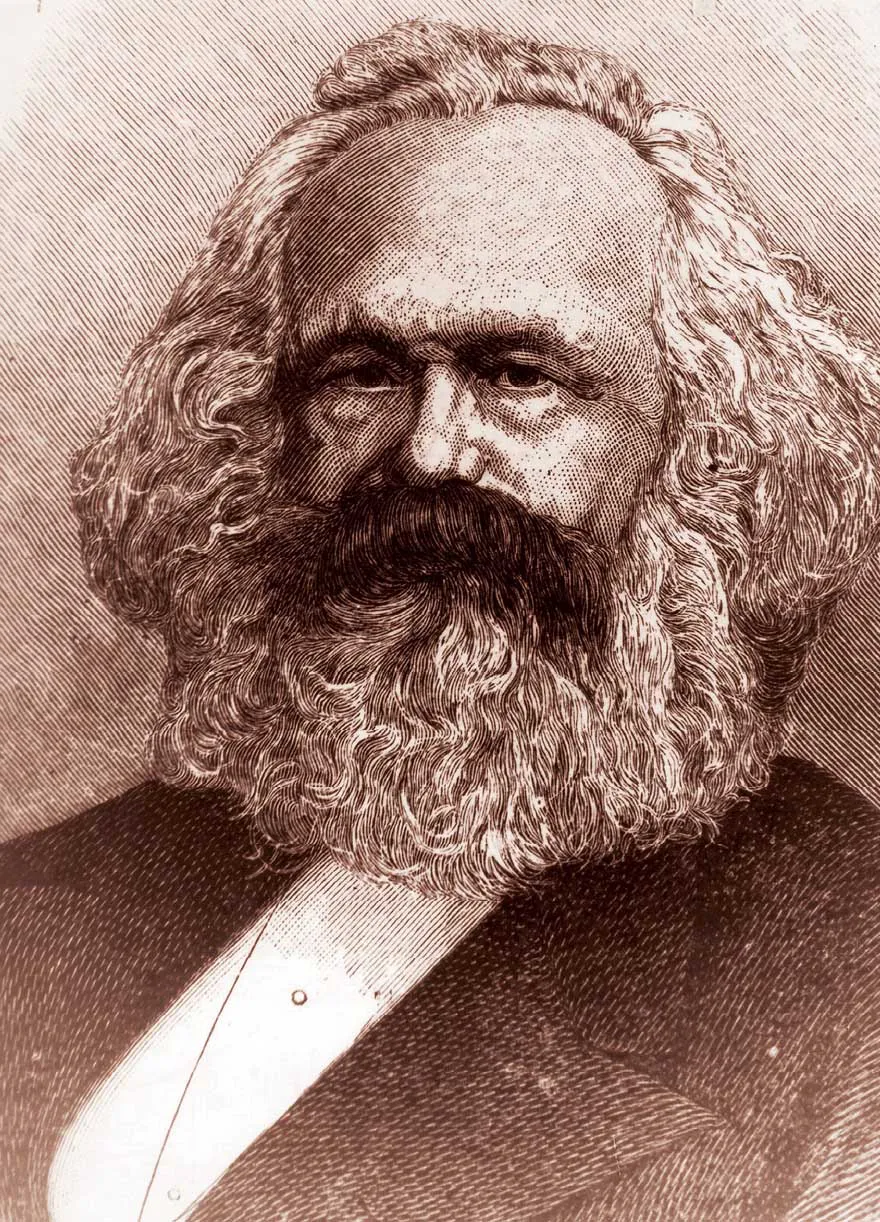

Karl Marx (1818–83).

Illustrated London News

The function of ‘religion’

Apart from an approach that assumes an inner experience, which underlies religious behaviour, scholars have used the term ‘religion’ for what they consider to be curious areas of observable human behaviour which require an explanation. Such people form theories to account for why it is people think, for example, that an invisible part of their body, usually called ‘the soul’, outlives that body; that powerful beings control the universe; and that there is more to existence than what is observable. These theories are largely functionalist; that is, they seek to determine the social, psychological, or political role played by the things we refer to as ‘religious’. Such functionalists include historically:

• Karl Marx (1818–83), whose work in political economy understood religion to be a pacifier that deadened oppressed people’s sense of pain and alienation, while simultaneously preventing them from doing something about their lot in life, since ultimate responsibility was thought to reside in a being who existed outside history.

• Émile Durkheim (1858–1917), whose sociology defined religious as sets of beliefs and practices to enable individuals who engaged in them to form a shared, social identity.

• Sigmund Freud (1856–1939), whose psychological studies prompted him to liken religious behaviour to the role that dreams play in helping people to vent antisocial anxieties in a manner that does not threaten their place within the group.

Although these classic approaches are all rather different, each can be understood as functionalist insomuch as religion names an institution that has a role to play in helping individuals and communities to reproduce themselves.

The family resemblance approach

Apart from the essentialist way of defining religion (i.e. there is some non-empirical, core feature without which something is not religious) and the functionalist (i.e. that religions help to satisfy human needs), there is a third approach: the family resemblance definition. Associated with the philosophy of Ludwig Wittgenstein (1889–1951), a family resemblance approach assumes that nothing is defined by merely one essence or function. Rather, just as members of a family more or less share a series of traits, and just as all things we call ‘games’ more or less share a series of traits – none of which is distributed evenly across all members of those groups we call ‘family’ or ‘games’ – so all things – including religion – are defined insomuch as they more or less share a series of delimited traits. Ninian Smart (1927–2001), who identified seven dimensions of religion that are present in religious traditions with varying degrees of emphasis, is perhaps the best known proponent of this view.

‘Religion’ as classifier

Our conclusion is that the word ‘religion’ likely tells us more about the user of the word (i.e. the classifier) than it does about the thing being classified. For instance, a Freudian psychologist will not conclude that religion functions to oppress the masses, since the Freudian theory precludes coming up with this Marxist conclusion. On the other hand, a scholar who adopts Wittgenstein’s approach will sooner or later come up with a case in which something seems to share some traits, but perhaps not enough to count as ‘a religion’. If, say, soccer matches satisfy many of the criteria of a religion, what might not also be called religion if soccer is? And what does such a broad usage do to the specificity, and thus utility, of the word ‘religion’? As for those who adopt an essentialist approach, it is likely no coincidence that only those institutions with which one agrees are thought to be expressions of some authentic inner experience, sentiment, or emotion, whilst the traditions of others are criticized as being shallow and derivative.

So what is religion? As with any other item in our lexicon, ‘religion’ is a historical artefact that different social actors use for different purposes: to classify certain parts of their social world in order to celebrate, degrade, or theorize about them. Whatever else it may or may not be, religion is at least an item of rhetoric that group members use to sort out their group identities.

Russell T. McCutcheon

chapter 2

Phenomenology and the Study of Religion

There is...

Table of contents

- Contents

- 1 Understanding Religion

- 2 Religions of Antiquity

- 3 Indigenous Religions

- 4 Hinduism

- 5 Buddhism

- 6 Jainism

- 7 Chinese Religions

- 8 Korean and Japanese Religions

- 9 Judaism

- 10 Christianity

- 11 Islam

- 12 Sikhism

- 13 Religions in Today’s World

- 14 RapidFact-Finder

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Introduction to World Religions by Christopher Partridge in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & Religion. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.