eBook - ePub

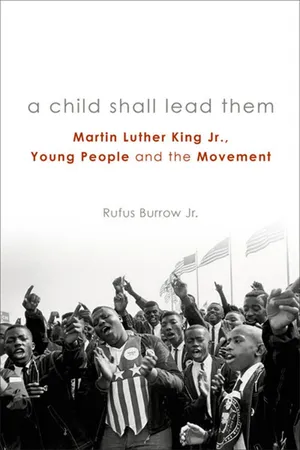

A Child Shall Lead Them

Martin Luther King Jr., Young People , and the Movement

- 150 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Half a century after some of its most important moments, the assessment of the Civil Rights Era continues. In this exciting volume, Dr. Rufus Burrow turns his attention to a less investigated but critically important byway in this powerful story—the role of children and young people in the Civil Rights Movement.

What role did young people play, and how did they support the efforts of their elders? What did they see—and what did they do?—that their elders were unable to envision? How did children play their part in the liberation of their people?

In this project, Burrow reveals the surprising power of youth to change the world.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A Child Shall Lead Them by Rufus Burrow Jr. in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Theology & Religion & History of Christianity. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

4

Mississippi

Made to Disappear

As vicious and violent as Deep South cities such as Birmingham, Alabama—the bombing capital of the United States of America—was toward blacks during the civil rights struggle, it is not an exaggeration to say that places in Mississippi such as McComb, Philadelphia, and the entire Delta region were in an entirely different category. Other Deep South cities such as Birmingham and Selma were without question dangerous places for black people, but arguably no state in the nation was more dangerous for blacks than Mississippi, especially counties in the southwestern part of the state, for example, Pike, Amite, and Walthall. This region of Mississippi seethed with hatred and disdain for black humanity, and there seemed to be no limits or restraints on white violence against blacks. This, in part, is what prompted historian Howard Zinn to say that Mississippi is not just a closed society like much of the South, but a locked society, for which the key must be found.[1]

Reflecting on what it meant to be a black Mississippian, Myrlie Evers, widow of slain civil rights activist Medgar Evers, spoke for all blacks in the state when she said: “To be born black and to live in Mississippi was to say that your life wasn’t worth much.”[2] This said it all. White Mississippians considered blacks to be nonpersons, and thus not worthy of being treated even with the respect one might give a dog, assuming that dogs have rights and are in any way due respect by human beings. This helps to explain why it was seldom sufficient in the minds of white racists to murder blacks who in any way stood up as human beings and demanded respect. Frequently, racist whites in the state felt they had first to savagely beat, disfigure, and break every bone in a black victim’s body. A young fourteen-year-old black boy from Chicago was a case in point.

Emmett Louis Till had been indescribably brutally beaten to the point that he was not recognizable, and then murdered near Money, Mississippi on August 24, 1955. His body was wrapped in barbed wire, attached to a heavy metal weight, and dumped like a piece of garbage in the Tallahatchie River by men who considered themselves to be good, born-again Christian people. These men, Roy Bryant and J. W. Milam, saw no inconsistency between their profession of the Christian faith and what they did to young Till, a human being created in God’s image. Since Till’s mother, Mamie Bradley, insisted on an open-casket funeral so that all the world could see what white racists had done to her child, the photo of the completely unrecognizable face (published in Jet magazine) was a clear reminder to blacks, particularly to black males, that Mississippi was the most dangerous place in the nation for them.

Although the state of Mississippi had a black population of 45 percent, the highest in the nation at the time, it also held first place in a number of less-than-admirable ways during the civil rights movement. It was the poorest state in the nation; led the nation in brutal beatings, lynchings, and disappearances of blacks; during the decade of the 1950s more blacks migrated from the state than any other (approximately 315,000); 75 percent of its college graduates, virtually all white, left the state. In addition, Mississippi had fewer medical professionals, for instance, doctors, nurses, and lawyers “per capita than any other state in the nation. In 1959, the NAACP counted only one black dentist, five black lawyers, and sixty black doctors in the entire state.”[3] Population wise, blacks held a clear majority in many counties and could have easily controlled things politically through the vote. Barely 5 percent of the state’s black citizens were in fact registered to vote. The chief criterion for accessing the ballot box was one that blacks did not have—white skin.

It was virtually impossible for blacks to obtain a good job in Mississippi. The state and its constitution placed little emphasis on education in general, and for blacks in particular. In fact, Mississippi law did not require that blacks attend elementary and secondary schools. This was linked to the requirement for voting. That is, one had to read or interpret a select passage from the state’s constitution to the satisfaction of white-supremacist registrars. This was obviously a problem for most blacks in the state, since so many were uneducated and unable to read. Of course, when more blacks began learning how to read, the constitution was changed, requiring that one had to be able to read and interpret a select passage. Most blacks could not read or interpret the constitution any more than many of their white counterparts, because they were kept out of the educational system. And when they did attend school, they received a second-rate education at best. Indeed, state officials did not even put a premium on bookstores and public libraries, which says something not only about the black population, but about those who were in law enforcement, government, business, and such. There was, across the board, a high level of illiteracy in the state. Ignorance ruled, and it was so deeply entrenched among many whites that they had no sense of just how ignorant they were as they sought to rule over blacks. Just as many blacks could not read and interpret select passages from the state constitution, many whites could not either. But they were, after all, white.

It should come as no surprise that most white Mississippians did not try in the least to hide their preference for life in a segregated state, with virtually no social, welfare, and legal responsibility toward blacks. The social, educational, legal, and political systems in the state existed primarily for the protection and well-being of whites. Those systems also existed in order to make life miserable for blacks.

Politicians, judges, prosecutors, and law enforcement officials were blatant racists and staunch advocates of states’ rights. They loathed what they perceived as outside interference, including the federal government. There was utter resentment of the presence of the NAACP, SNCC, CORE, and SCLC, as well as local civil rights groups in the state. More often than not, law enforcement officials and the courts were in collusion with their white-supremacist neighbors and relatives who committed brutal acts of violence against civil rights activists. “There was no protection from the local racists at all, for those who were supposed to protect you, the state and local police, were agents of the forces of resistance, and in the most infamous lynching soon to come, the murder of three civil rights workers in Neshoba County in 1964, the sheriff and deputy sheriff had been the murderers.”[4] This was not different than in other counties in Mississippi, for example, Franklin. “The Klan ruled the county and feared no one, including the law. The Klan was the law. The Klan even threatened to kill FBI agents. . . . [T]hey held Franklin County, black and white, under what lawmen would call a virtual reign of terror.”[5] Moreover, Klansmen who terrorized and murdered blacks were frequently considered to be “serious churchgoers,” if only in the sense of regularly showing up, participating in the liturgy, offertory, and so on. “Serious” in this sense generally had nothing to do with a commitment to the highest principles of Christianity. In far too many instances the enemy for black residents and the student activists in Mississippi was the local authorities in virtually every area, including the religious establishment. As we will see, it is no wonder that most black Mississippians rejected nonviolence in favor of self-defense, and thus owned guns. Many were not afraid to use those guns in defense of self, family, and friends.

Youthful Freedom Riders Bound for Mississippi

Bernard Lafayette was one of the original student activists in Nashville, Tennessee who came under the influence and nonviolence training of James Lawson. When Lafayette, James Bevel, John Lewis (now longtime U.S. Congressman), C. T. Vivian, and Lawson boarded a bus in Montgomery, Alabama in 1961 for the Freedom Ride to Jackson, Mississippi, the image that came to Lafayette’s mind about black people in that state was of them hanging from trees with ropes around their necks[6]—what Billie Holiday called in her 1939 recording, “Strange Fruit,”[7] that is, innocent black bodies hanging from trees. Indeed, in his reflections on black power and his urging that black power advocates not imitate the worst in white values and practices, Martin Luther King reminded his people that blacks had not indiscriminately lynched and murdered white people, and had not “hung white men on trees bearing strange fruit.”[8] So this idea of strange fruit, of black bodies hanging from trees in Deep South towns, was emblazoned in the psyche of southern blacks.

Without question, Mississippi, particularly the Delta and Southwest region of the state, was anything but black people friendly. It was, rather, a most intimidating, life-threatening place for those with black skin, no matter what part of the country they were from, and no matter what was their social status. In some ways, Mississippi was just as intimidating and life-threatening to well-meaning white activists (including students) from the North as well as the South. White-supremacist segregationists could be—and frequently were—just as violent and murderous toward white activists as their black counterparts. In fact, because they were considered “nigger lovers” they were generally beaten more severely than blacks. For example, Rabbi Arthur Joseph Lelyveld sustained a savage beating in Hattiesburg during Freedom Summer. Lelyveld had accompanied a small interracial group of youthful civil rights activists, who had been handing out leaflets. They were attacked by two white men with tire irons. The students remembered what they learned in the nonviolent workshops about taking nonviolent self-defensive positions of crouching and covering their heads if attacked. Unfortunately, the rabbi either forgot what was learned, or had not undergone the training before accompanying the youths. Since he remained standing during the attack, his head was exposed, and was an easy target for the repeated blows by the savage attackers.[9]

Blacks had no civil and political rights in Mississippi, nor could they count on the police and the judicial system for protection and justice, for these were often complicit in terrorist acts against blacks, and whites who supported the civil rights movement. This is surely a reason why many black Mississippians owned guns and rejected nonviolence; who were staunch believers—like Hartman Turnbow—that blacks had to learn to speak the language that whites speak to them. If whites are nonviolent with blacks, blacks should be nonviolent with whites. But if whites are violent with blacks, blacks should be violent with their attackers.[10]

Julian Bond, one of the founders of SNCC, recalled that they once had a big debate in SNCC about carrying guns. Although most of the original SNCC activists (affiliated with the Nashville Student Movement) were against weapons of any kind, volunteers who were Mississippi residents insisted on the need to carry guns. Indeed, Bond reflected: “Almost everybody with whom we stayed in Mississippi had guns, as a matter of course . . .”[11] A white college volunteer in the Mississippi Summer Project in 1964 wrote to his parents that virtu...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Table Of Contents

- Foreword: Beyond Emmett Till

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- Montgomery

- Sitting-In and Taking a Ride for Freedom

- Birmingham and the Children’s Crusade

- Mississippi

- Selma

- Who Will Carry the Freedom Struggle Forward?

- Index