![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction and historical background

The historical figure of Queen Arsinoë II1 has long been a topic of discussion. Her involvement in political affairs has interested a broad range of scholars over the years, engaging dedicated Egyptologists and classicists alike. However, in the eyes of modern scholars her political role has always surpassed her religious position in her contemporary society, while as a subject of study she has remained in the shadow of her more famous descendant Queen Cleopatra VII. These two queens are, however, connected through more than their royal status. They were both deified in their own right, receiving religious attention from Greeks and Egyptians alike. They were also closely involved in the established cult of the royal family, venerated as the daughters, sisters and mothers of their Macedonian dynasty.

This Ptolemaic queen and ruler cult was expressed in various ancient media, one of which consisted of reliefs. In a period when (hieroglyphic) writing was limited mainly to the highest social strata, including the priesthood and the royal court, the relief scenes, with their images, could address all levels of society, providing a strong and comprehensible message for literate and illiterate viewers alike. Each iconographic unit had an important place in a well-chosen composition, incorporating all parts of the figures as well as the full scene into a complete and structured setting. The pictorial elements represented in each figure of the scene allowed individualism, thus separating one figure from another, in an iconic context where one of the most important attributes was the crown.

Such an attribute – a unique crown – was created and developed for Queen Arsinoë. It was a crown composed of strategically chosen iconographic units intended to set this queen apart from other royal women as well as from female deities. This crown was reused by two later Ptolemaic queens, Cleopatra III and VII, both of whom held an official status equal to that of the king. The crowns and their position within the scene, as well as their relationship with surrounding pictorial units, provide the modern world with a key to the understanding of a period in which respect for ancient traditions was vital, and to which traditions a new foreign dynasty had to adjust. A study of this unique Ptolemaic crown and its later variations will throw light on both the creation and the development of an iconographic programme introduced by the royal court as a part of a conscious politico-religious agenda.

The reliefs, following an ancient Egyptian tradition, show a great assortment of iconographic manifestations, each unique in their own way. Seemingly, the Macedonian rulers further developed this ancient artistic programme in order to reach out to both the indigenous people of Egypt and the increasing Greek immigrant population by introducing a programme of assimilation. Two ancient civilisations, each one with its own strong conventional symbolic values, merged in this unstable political period, the Hellenistic era: thus ancient Egyptian mythological creatures, vividly illustrated in anthropomorphic forms or with features of the natural fauna, met a contemporary set of beliefs expressed in traditional Greek religion. These two cultures combined to produce a powerful dynasty resting on established traditional dynastic conventions of politics in a country where royal events were carefully documented and distributed to the people.

The most obvious means of reaching the population was iconography, which offered the opportunity to manipulate size, position and time. In order to inform the population of the new dynasty the pre-existing iconographic programme was developed to include every aspect of the Ptolemaic queens’ cultural context, Greek and Egyptian. The Ptolemaic kingdom, conscious of its dual cultural heritage, enabled the development of a means of artistic expression in which each pictorial element, resting on a highly individual symbolism, merged in a full composition. The crown, as a personal attribute and a symbol of hierarchic position, was one of the most important details in a scene, and it was thus unsurprising that a special crown was created for Queen Arsinoë in order to convey her rank and position in society. This attribute contained a statement so powerful that it remained an influential, recognisable symbol of queenship and divinity throughout the entire dynasty. Religion, power, politics and pictorial symbolism thus meet in one personal attribute, the crown of Arsinoë.

Queen Arsinoë

Images of Arsinoë appear in a broad spectrum of iconographic media, depicting this historical figure in a Greek as well as Egyptian cultural setting, and as queen and goddess alike. Although her descendant Cleopatra VII is better known to the modern world, the larger part of the iconographic material depicting a Ptolemaic queen does in fact represent Arsinoë. The daughter of Ptolemy I and Berenice I, Arsinoë was born in Alexandria c. 316 BC (traditionally calculated on the commentaries on her marriage in Plut. Vit. Demetr. 31). At the age of 16, c. 299 BC, she was married to Lysimachus of Thrace, an ally general of Ptolemy I, who was many years her senior. Soon after the marriage the couple parented three sons, Ptolemy (c. 298 BC), Philip (c. 297 BC) and Lysimachus (c. 294 BC) (Just. Epit. 24.3). During her time as the Lysimachus’ spouse she received great honours, among other things the cities of Heraclea, Amastris and Dium, all given to Arsinoë by her husband (Plut. Vit. Demetr. 31; Paus. 1. 10). She also received the city of Ephesus, changing its name to Arsinoë c. 293 BC (contemporary coins bear witness to this: Svoronos 1904, nos 875–892; Mørkholm 1991; Troxell 1983). After disputed circumstances surrounding the death of Agathocles, the son of Lysimachus from his previous marriage, Lysandra, Arsinoë’s half-sister and wife of Agathocles fled to Seleucus at Babylon, seeking support. Seleucus supported Lysandra and fought Lysimachus, resulting in the death of the latter in the battle of Corupedium in 281 BC (for a discussion concerning the political role of Arsinoë in the murder of Agathocles and Lysimachus’ death see Sviatoslav 2007). According to Justin, Arsinoë temporarily fled to Ephesus to regain strength and with the help of her sons she continued to Cassandrea, where she commanded a garrison to defend the territory (Just. Epit. 24.2).

While defending the remaining territories Arsinoë’s half-brother, Ptolemy Keraunus, defeated Seleucus and became the ruler of Macedonia. Keraunus persuaded Arsinoë to marry him, his aim being the annexation of the power held by her and her children. This marriage ended shortly thereafter when Keraunus killed two of Arsinoë’s three sons (Just. Epit. 24.3). Arsinoë fled from Cassandrea to the island of Samothrace, where she later erected a temple in honour of the gods who helped her on the island (Just. Epit. 24.3). From Samothrace Arsinoë returned to Egypt. The sources describing the period between Arsinoë’s time at Samothrace and her marriage with Ptolemy II are fragmentary, and no absolute information is yet available (e.g. Theoc. Id. 17,128; Paus. 1.7.1; Ath. 621A; Plut. Mor. 736F; cf. Cameron 1995, 18–22). During her period as queen of Egypt she was involved with the royal fleet and is recorded participating with her brother in battles. She is also described by the text of Theocritus as a queen of the people when arranging a play honouring Adonis and Aphrodite (Theocr. Id. XV). She participated in the Olympics, where she won three events for harnessed horses during the summer of 272 (or 276) BC (P. Mil. Vogl. VIII 309, AB 78; cf. Grzybek 1990). She received queenly status during her lifetime but also a divine position when the cult of the theoi Adelphoi was instituted.

The cultic roles of Arsinoë

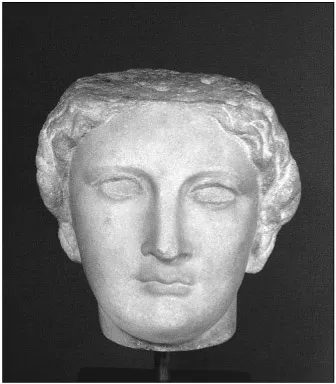

Owing to the lack of archaeological evidence for the crown of Arsinoë, modern scholars are limited to the information provided in the artistic and textual forums. Her depictions have been presented and studied by various scholars over the years: thus her portrait on coins was studied initially in the grand volumes of Svoronos (1904, nos 875–892) and her Greek queenly position on the faience oinochoai by Thompson (1973), while her representations on sculptures in the round, terracottas, cameos, figurines and, of course, reliefs, have also been the subjects of study (Figure 1). Although there are a few three-dimensional representations of Arsinoë wearing her personal crown, the main material is found in reliefs (cf. Ashton 2001a; Albersmeier 2002), all of which are of a religious type. Although Arsinoë is illustrated as a queen, the scenes and full pictorial settings in which she appears have highly cultic connotations.

Figure 1. Greek-style portrait of Queen Arsinoë II, Bonn, Akademisches Kunstmuseum der Universität, B 284: photo by J. Schubert © Antiquities Museum, Bonn.

The cult of Arsinoë was multi-faceted and covered a great time span, from the reign of Ptolemy II throughout the Ptolemaic dynasty and into the Roman period (P. Mil. Vogl. 2, I.IV, dated 2nd century AD, describes Arsinoë in direct association with Aphrodite/Hathor). (One could argue that the cultic position of Arsinoë survived also into medieval times, since her name was still actively in use as designating several cities and the entire Fayyum province.) She received her divine status during her lifetime, initially together with Ptolemy II as the theoi Adelphoi, the sibling gods. Her individual cultic status as thea Philadelphos, the divine sibling-lover (brother-lover), is still today a contentious topic over which scholars remain in dispute (e.g. Quaegebeur 1971a; 1971b; 1978; 1988; 1989; Hazzard 2000, esp. chapter 5). The cult of Arsinoë also assimilated the queen with the Greek goddess Aphrodite, to whom pious worshippers dedicated much devotion. Her connection with other Greek deities is attested in more private forms throughout the Alexandrian area. It is, however, important to introduce at this point the religious role Arsinoë had in Egyptian society, where she was venerated not only in her queenly position as the earthly manifestation of Hathor but also in her own right. The cultic roles of Arsinoë should be considered individually, as each had its own priesthood, its own religious practices and its individual official as well as private meanings. A summary of these roles – the eponymous cult of theoi Adelphoi; the individual eponymous cult of Arsinoë; private cults of Arsinoë; the dynastic Egyptian ancestor cult of the mr-sn; and the native Egyptian cult of Arsinoë Philadelphos – will be provided here, while a more detailed account is provided in later chapters.

The eponymous cult of theoi Adelphoi

Although the material focuses on the Egyptian cult of Arsinoë, an introduction to the Greek counterparts is still important, as some cultic aspects of Arsinoë bridged cultural boundaries in this regard. The eponymous cult was Greek in its essence but, as will be further clarified below, it also had a strong similarity with the dynastic cult anchored in ancient Egyptian society. While all the scenes considered here are Egyptian in their artistic style, there is a thread linking the two cultures together: although the scenes are Egyptian in their setting, the official designations of the Ptolemaic couples are Greek in origin. The debate over whether these official cultic titles were translated from one language to the other or created from scratch contemporaneously (e.g. Winter 1978, 153f) is not addressed here. Regardless of chronological development or linguistic influence, the scenes at hand here describe the couple, Arsinoë and Ptolemy II, as the sibling gods. There is only scanty and fragmentary evidence that the Greek eponymous cult of the second Ptolemaic couple functioned in actuality as a cult in the truest sense. The main extant evidence comes from the dating formula, preserved in thousands of papyri dating to the entire Ptolemaic dynastic period (Clarysse and Van der Veken 1983; Fraser 1972, 219; P. Mil. Vogl. 309, 74 A–B; Bastianini et al. 2001, 200–202; Bingen 2002, 185–90; Barbantani 2005, 148; cf. Gutzwiller 2005). In the main these are documents which list the names of the serving priests of the eponymous couple (mainly associated with dates, names and geographic areas); only rarely do they refer to an existing sacred liturgy.

Arsinoë and Ptolemy II were deified as theoi Adelphoi, the sibling gods, in the year 272/271 BC (P. Hib., 199, II. 11–17; Hauben 1970; Mooren 1975, 58–60; Hölbl 2001, 94f.). They were included in the official eponymous cult and were given their own priesthood, which designated each year. The cult of the theoi Adelphoi was placed immediately after the already established cult of Alexander the Great in the official records. The deification of the second Ptolemaic couple established a regal link with Alexander not only as his royal successors but, possibly more importantly, as his divine descendants. They were venerated in the chthonic centre of Alexandrian worship, the Sema, side by side with the immortalised Alexander (Fraser 1972, 215). This reconnection to previous rulers was a socio-religious phenomenon that already existed in ancient Egyptian culture and was mainly expressed through the ruler cult. The closest comparison that can be found in Greek soci...