![]()

CHAPTER 1

The nature of the deceased: constituent parts, character and iconography

The body of a man is very small compared with the spirit that inhabits it.1

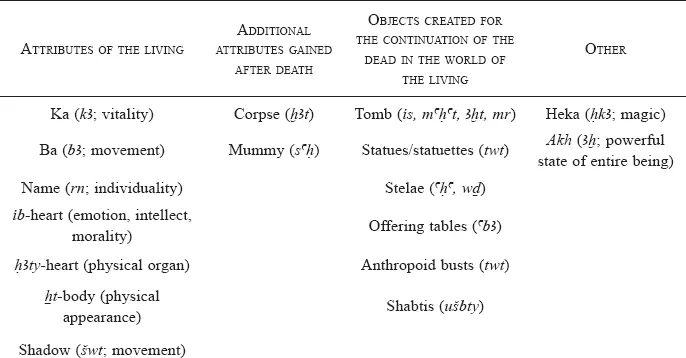

In order to discuss ancestors, cults, and the relationship between the living and the dead, it is first necessary to consider what and who the dead were in Egyptian thought, and how they differed from the living in iconography and character. The essential elements of the living and the dead are listed in Table 1. Most aspects of the living were maintained beyond the grave, but acquired new meaning and focus in the transformative process from life to death.

Characteristics of and terminology relating to the dead

Death resulted in the fragmentation of the individual person, forcing apart the physical from the spiritual. According to Assmann,2 a newly deceased person emerged in their various aspects or constituent elements, which took on a life of their own. The most important of these elements were the ba, ka, ib-heart,3 name, shadow, and akh, along with the image/statue (twt), mummy (s‛ḥ), and corpse (ẖȜt).4 A unique text in the 18th Dynasty tomb of Amenemhet5 includes five personifications of destiny, namely fate/destiny (šȜἰἰ), lifetime (‛ḥ‛w), birthplace (msḫnt),6 development/fortune (rnnt), and ‘personal creator god’ (ẖnmw), as well as physical objects (such as offering stone, stela, tomb), and ‘all his manifestations (ḫprw.f nbw)’.7 Magic (ḥkȜ) is another constituent part of the dead referred to alongside the ba, akh and shadow in the Coffin Texts,8 and as something that should not be removed from the deceased in the afterlife in the Book of the Dead.9 The many components of the dead person enabled him to pervade the entire cosmos,10 and it is often not possible to differentiate between humans and deities in the underworld books because of the manner in which they are mixed together.11 Equally, the blessed deceased may be identified as Sia, the personification of perception, who is shown on the right hand of Re.12

Table 1: Attributes of the living and the dead.

The only physical attribute acquired in death is the mummified corpse, which replaces the ẖt-body, and through the embalming process regains some of the deceased individual’s physical appearance, with facial features being augmented by the mummy mask. Statues and statuettes, along with depictions on stelae, substituted for the visible form of the deceased (see Chapter 2), while emphasis is placed upon the ka and ba to replace the living essence and the deceased’s ability to move and consume food and drink, capacities that were interrupted by the individual’s death. Here I discuss in particular the ba, akh, and shadow, as these are the elements of the individual that could travel, and thus affect the living, and they are most frequently referred to in funerary literature.13 John Gee has suggested that the terms bȜ, Ȝḫ, and nṯr (god) were related in the Egyptian mind in a hierarchical way.14 While ‘gods’ in the sense of blessed dead are undoubtedly lower on the scale than major deities, to give individual characteristics ranks in this way may not be particularly meaningful; all parts were integral to the survival of the whole being.15

Constituent elements of the dead

The ba

The ba has been likened by Nadia el-Shohoumi to the modern Egyptian rūḥ,16 and is defined by Žabkar in relation to the deceased (as opposed to the gods or the king) as a representation of an individual, ‘the totality of his physical and psychic abilities’:17 personified in the Coffin Texts, it becomes a man’s alter ego, and by performing physical functions for him, is one of the means by which he continues to live. Žabkar18 was adamant that ‘ba’ could not be translated as ‘soul’, either internal or external, and he considered the Egyptian concept of man to be monistic, not an element or form of manifestation of the man, but the man himself. His views have not been universally accepted, and most scholars still interpret ba as ‘soul’ or part of the spiritual and physical dimensions of an individual.19 Žabkar20 also rejected the idea that the ba existed during a person’s lifetime, instead proposing that man lives in his ba after death, rather than possessing it while alive, which leads to a very different translation of certain texts such as the Instructions of Ptahhotep and the Instruction for King Merikare.21 In support of Žabkar’s hypothesis, it seems likely that the Dialogue Between a Man and his Ba22 represents an introspective philosophical debate between a man and his conscience and reflects the beliefs and doubts of the period in which it was written.23

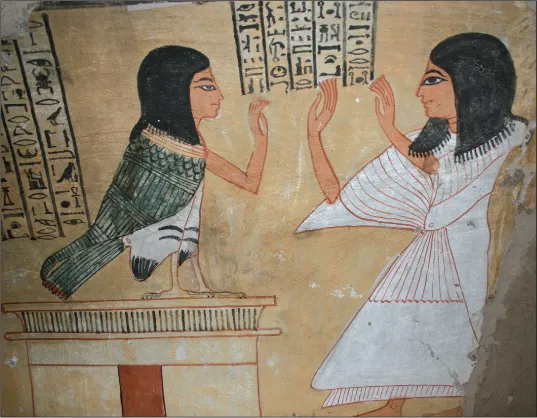

That the ba embodied the ability of the deceased to move around during the day is indicated by its avian form, initially represented by a jabiru stork,24 which by the New Kingdom was often replaced by the human-headed falcon (Figure 1). A specific quality of the ba was also that it could assume any form it desired25 as stated, for instance, in the Opening of the Mouth ritual.26 The capacity of the ba to take flight was essential in enabling the deceased to communicate with the gods and the dead,27 and to ensure the preservation of the body through the provision of sustenance.28 In the 19th Dynasty tomb of Paser the ba is depicted giving the breath of life to the mummified corpse as part of the embalming ritual.29

Figure 1: The tomb owner greets his ba. The text behind the latter is a spell for ‘being transformed into a living ba’. Tomb of Inherkhau (TT 359), Deir el-Medina, 20th Dynasty.

Baw – plural of ba30 – is interpreted by Borghouts as a form of divine retribution documented by the expression bȜw nṯr ḫprw, ‘a manifestation of a god has come about’,31 and the baw in this sense may be understood as manifest in the ba. Whereas the king’s divine status made it possible for him to send his ba to places where he was not physically present,32 when ordinary citizens are said to send their baw33 one may assume that they are doing so from or within the next world. The mobility of the ba could create problems for the living, perhaps in terms of some kind of haunting, or the disruption of daily life as indicated...