![]()

Chapter 1

Historical and Geographical Background

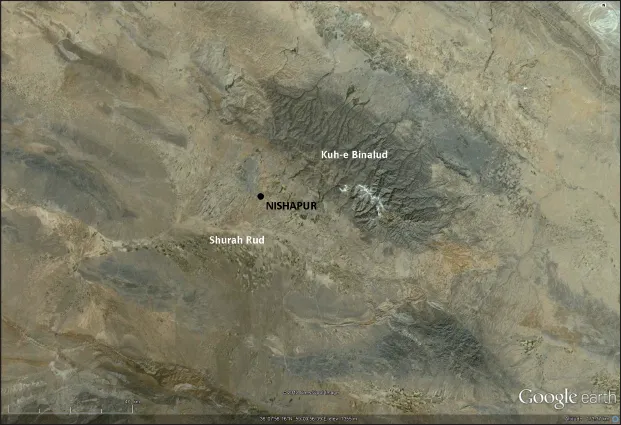

1. Geographical setting of Nishapur

Nishapur is located in the Khorasan region, in the eastern part of Iran (Fig. 1). This part corresponds to the northern boundaries of the Iranian Plateau, beyond which the landscape corresponds to the Central Asian steppe land. The territory of the archaeological site is situated in a fertile zone (see Nasir al-Din Shah Qajar 1889, 171). It is limited on the northeast by the foothill of the Binalud range (Fig. 2), culminating at 2000 m up to the plain, and on the southwest by the brackish and marshy course of the Shurah Rud (also Shurirud) above the site (Barthold 1984, 95). Some southern areas of the plain are, in fact, unsuitable for agricultural exploitation. From the mountain in the north, rain and snow fall to irrigate the farmland below. Thus, the Nishapur area is irrigated upstream by surface precipitation and downstream by a system of draining galleries known as qanats. The orientation of the urban plan is determined by the course of water flows descending from the Binalud Range.1

Figure 1: Geographical map of Iran (© Google Earth 2012).

Figure 2: Geographical map of the Nishapur area (© Google Earth 2012).

The archaeological area is today located around 2 km from the southeastern part of the modern city (Fig. 3). Between them, the Mausoleum of Omar Khayyam is set inside a magnificent and well-maintained garden. Fortunately, the archaeological zone has been, more or less, spared from modern urbanization. The reasons for this shift in urban location are probably due to various historical and natural events, such as several invasions and earthquakes (see the historical setting of Nishapur). However, the sole railway branch to the east, principally to Mashhad, constructed in the middle of the last century, crosses the site from northwest to southeast, cutting the archaeological landscape between the oldest part (Qohandez and Shahrestan) and the probable Great Mosque of the ancient city.

Nishapur was an important crossroads linked to Central Asia and China by way of Merv, Paykend, Bukhara and Samarkand; to Afghanistan and India by Herat; to the Persian Gulf by Yazd and Isfahan; and finally to the west by Damghan, Rayy and Hamadan. It was one of the main cities on the Silk Road (Rtveladze 2009, 226). The last excavation has shown that, during late antiquity and the medieval epoch, the city had the dual characteristic of a residential as well as a production place. These characteristics are specific to different periods of the city. Nishapur could be considered as an important residential city as well as a ‘storehouse’ along this segment of the Silk Road. The city was, like the other cities of the Silk Road, strongly protected by ramparts. Its position between the plain and the mountain, situated in a natural corridor on the main route of the caravan road, easily exposed it to strong attacks and invasions.

Figure 3: Nishapur, satellite view of the archaeological area (© Google Earth 2012).

Figure 4: Nishapur, Qohandez, present state of the site ruins (© Collinet 2006).

Following a centuries-long period of abandonment, the medieval site was turned into a quarry and exploited by brick makers (d’Allemagne 1911, 129) (Fig. 4). Their first actions were to take the baked bricks of the late occupation on the top of the site and reuse them to build the surrounding villages. Later, the mud brick buildings at a lower level were destroyed in order to fertilize fields that covered the site and the surrounding plain (ibid., 117–118). The occasional discovery of antique objects, many of them very valuable, promoted illegal excavations.

2. Former excavations and studies

The American and Iranian excavations in Nishapur

The Metropolitan Museum’s excavations

The Metropolitan Museum’s excavations, headed by Walter Hauser, Joseph M. Upton and Charles K. Wilkinson, took place between the years 1935 and 1940. Halted by World War II, the work ended with a final mission in 1947. The leading aim of the excavations was clearly the discovery of objects and architectural decorations for the Museum (Hauser 1937; Wilkinson 1937) and the drawing up of their chronology. The architectural ornaments and the artefacts discovered were divided – under the authority of the Iranian Ministry of Education and Fine Arts and following the Iranian antiquities law of 1930 – between the MET in New York and the Tehran Museum (Hauser 1937, 27; Wilkinson 1961, 103).

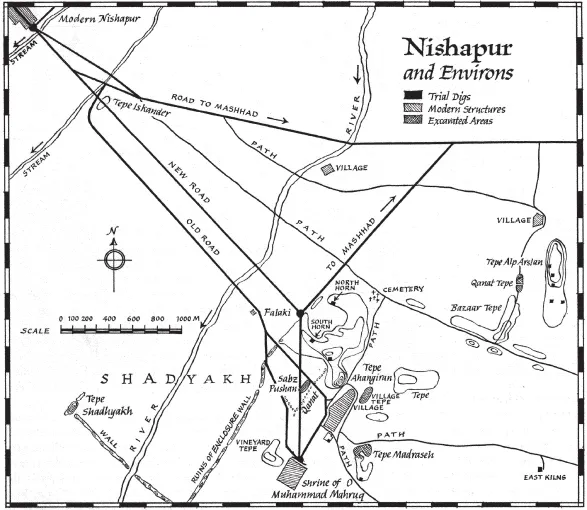

In the parts of the archaeological area of Nishapur which were not urbanized, the excavations were nevertheless limited by fields and public paths. The excavations were mainly focused on the area situated between the site of Shadyakh and the citadel or Qohandez (Fig. 5).

After several test digs and the uncovering of restricted parts of other mounds, the American excavations were principally concentrated on two mounds: ‘Tepe Madraseh’ and ‘Tepe Sabz Pushan’. These two areas produced most of the Nishapur objects owned by the two museums.

The final publications of the excavations and of the finds were written by Wilkinson (after the death of Hauser and changes in Upton’s activities) and by other scholars who published the most important finds. They were released by the Metropolitan long after the interim reports published in the Bulletin of the Museum. The ceramics were first published by Wilkinson (1973). In his final report of the excavations proper, eventually released after his death (Wilkinson 1986), he essentially concentrates on the architectural decorations (stucco panels and wall paintings) discovered. Finally, the metal objects were studied by J. W. Allan (1982) and the glass wares by J. Kröger (1995).

The question of the Sasanian city

The American team did not identify any vestige of the Sasanian Period during the survey and the excavations of the site (Hauser et al. 1938, 4; Hauser and Wilkinson 1942, 119). In Wilkinson’s opinion, ‘the Sasanian city was used at least a whole century after its capture by the Arabs. The city was then rebuilt several miles away in the same plain as is customary in Persia’. This was the city excavated by the Museum (Wilkinson 1950, 61).

He considered that the mound on which the citadel stands (‘Tepe Alp Arslan’ or Shahr-i Kuhna) ‘was erected in the ninth century and formed the platform on which the citadel was built’ (Wilkinson 1950, 62), and that the Sasanian city was not in this area (1986, 39). Wilkinson was, on that subject, contradicted by Bulliet (1976) and Melville (1980, 103), and the recent excavations and the TL dates of some ceramic shards show that they were correct.

Figure 5: Nishapur and Environs, Excavation Map, The Iranian Expedition at Nishapur, The Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Metropolitan Museum of Art Image © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Drawing by Joseph P. Ascherel).

The Islamic Period

The American excavations revealed structures and objects dated by the excavators from circa the late 8th to the 12th centuries, but they did not provide any stratigraphy. A refined chronological sequence of the finds thus cannot be established. In addition, the objects discovered were not considered as stratigraphical assemblages. We do not know which types of ceramics, glass wares, metals and so on were contemporary with one another (Allan 1982, 13; Kröger 1995, 23). Thanks to the patient study of the glass wares and of their respective findspots, when known, Wilkinson’s opinion of the contemporary occupation of ‘Tepe Madraseh’, ‘Sabz Pushan’, ‘Qanat Tepe’ and ‘Village Tepe’ (Kröger 1995, 30), mostly circa the 10th century AD, was nonetheless confirmed.

Other mounds were explored at the beginning of the American researches. The citadel, locally called ‘Tepe Alp Arslan’ after the name of the Seljuk Sultan, was the object of seven test digs opened in order to identify the ruins. During these excavations, 13 coins, of which nine date from the 8th or early 9th century, were discovered (Wilkinson 1937, 19; Upton 1937, 37). Other test soundings were opened on different spots of the identified archaeological area: five near the tomb of Omar Khayyam and the mound ‘Tepe Ahangiran’; one trial dig in ‘Vineyard Tepe’ and in ‘Village Tepe’ (Wilkinson 1937, 17, 19–20), in which the ‘lower level’ was dug in 1937 (Hauser et al. 1938, 3).

The ‘Vineyard Tepe’ was more thoroughly excavated, but over a small area. The structures uncovered were probably part of an important house or palace adorned with stucco panels and wall paintings. The mansion discovered was contemporary with those in ‘Tepe Madraseh’, as suggested by coin finds, dating to the second half of the 8th–first half of the 10th century. It may have been abandoned earlier than ‘Tepe Madraseh’, as no fritware was discovered in ‘Vineyard Tepe’ (Wilkinson 1986, 188–189).

However, the main excavations were, at the same time, concentrated first in the locally named ‘Tepe Sabz Pushan’ (or the ‘green-covered mound’), where stucco panels and wall paintings were discovered (Upton 1936, 179–180; Hauser 1937). During the second season in 1936, six test digs were opened in the mound, in which several rooms were cleared (Wilkinson 1937, 8). The first construction of the building partially uncovered was dated (mainly with the oldest coins found) to the second half of the 8th century. Its repair was dated to around the late 9th century, and the stucco ornaments were attributed to the late 10th century. There were no traces of any Seljuk occupation in the structures (Hauser 1937, 32–35). Of the 38 coins coming from the tepeh, 31 are of the 8th or the early 9th century, and three are of the late 10th century. Wilkinson thus thought that there was a gap in the occupation of the site (Upton 1937, 37–38; Hauser et al. 1938, 6). The uncovering of the structures was extended in 1937 to find other ceramic wares and architectural decorations for the MET (Hauser et al. 1938, 3). Very many coins were again discovered: 12 are dated 731–760; 118 to 760–800; 24 to 800–820; 102 to 731–820 AD; and more than 15 Samanid coins were also found. In addition, the several Sasanian coins discovered in the excavations (one of which may be Parthian) were considered to be residual, for no other ‘pre-Islamic objects’ were found (ibid., 5–6). The area excavated was identified as a residential quarter of the city, which was already derelict at the arrival of the Seljuks in 1037 (ibid., 8) and abandoned by the 12th century (Wilkinson 1986, 221).

Coins of the Khwarezm Shah ‘Ala’ al-Din Muhammad ibn Tekish (596–617 H/1200–1220) were, in addition, found in the nearby area between the citadel and Shadyakh, to the northeast of ‘Tepe Sabz Pushan’ (Upton 1937, 38).

The most extensive excavation of the American team, in ‘Tepe Madraseh’, began during the 1937 season with a test dig (Hauser et al. 1938, 22) and was extended in 1938 (Hauser and Wilkinson 1942). The structures uncovered were interpreted as a ‘part of a palace or a series of government or public buildings’ and a mosque, lavishly adorned with brick designs, stucco panels and wall paintings. Most of the objects discovered during the American excavations come from this site. The occupation periods were dated between the early 9th and the 12th century. According to the excavators, the complex, which was partly cleared, was probably already ruined at the arrival of the Seljuks in 1037 (Hauser and Wilkinson 1942, 92–97). Three levels of structures were defined. In the lowest, a coin in the name of Harun al-Rashid was found on a floor. The ‘middle level’ is associated with most of the stucco panels discovered. Five dinars found in a well were associated with this phase: the latest are in the name of al-Mustakfiand dated 944 (?) (Wilkinson 1986, 57). The other numerous coins found in the structures were 42 from the second half of the 8th century; 23 from the 8th–9th centuries; 15 from the 9th century; 26 from the 10th century; and a few coins from the 11th–late 12th centuries and the Mongol Period (Ibid., 54). The brick inscription and the fragments of inscribed glazed tiles which were associated with the highest level of the structures (ibid., 110–116) nevertheless suggest an occupation during the 11th–12th centuries.

The Iranian excavations in Shadyakh, 1995–2002

Shadyakh is said to have been occupied firstly during the Tahirid Period in the early 9th century, and during the Samanid Period it may have become an integral part of the city of Nishapur. From 556 H/1161 AD onwards the population of Nishapur moved there (Melville 1980, 105–106, table II). The site was partly excavated by an Iranian team under the direction of Dr Labbaf Khaniki. The research was focused on the small enclosure which occupies the southern part of the site (Fig. 6): a large residence was discovered, which may have been the administrative centre and the mansion of the ruler. The rich stucco panels uncovered, as the quality of the numerous metalwares and fritwares also discovered in that site, corro...