- 112 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs

About this book

On release in the 1930s, Snow White became a milestone in animated film, Disney production and the US box office. Today its fans cross generations and continents, proving that this tale of the loveable, banished princess and her seven outstanding friends possesses a special magic that makes it both an all-time Disney great and a true film classic.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs by Eric Smoodin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Pre-History

Developing a reputation: Disney before Snow White

On 27 December 1937, a week after Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs premiered in Los Angeles, Walt Disney appeared on the cover of Time magazine.5 The film-maker shared space in the photograph with some of his newest stars, and received billing at the bottom: ‘Happy, Grumpy, Bashful, Sneezy, Sleepy, Doc, Dopey, Disney’. But the cover nevertheless elevated the studio head to a special status among American artists, as the equal of perhaps the nation’s greatest painter. The caption stated succinctly, ‘The boss is no more a cartoonist than Whistler,’ thus imagining a straight line from the iconic Whistler’s Mother to Disney’s latest princess, and letting readers know that Snow White marked a significant moment in American art and culture.

Time’s readers may have anticipated this moment and Disney’s new film, his first animated feature, for a number of years. Having entered the business in the early 1920s, Walt Disney had been famous for almost a decade, but by the early 1930s he had emerged as a special kind of American hero, the ideal combination of entrepreneur and artist. For Americans interested in culture, as well as for those just enthusiastic about movies, Snow White seemed the culmination of years of work, and a filmgoing experience unlike any other. Viewers understood the film to be a work of art, a great entertainment and ideal for all ages, a combination perhaps only achieved before by some of the films of Charlie Chaplin.

Disney’s esteemed reputation in 1937 was in marked contrast to the earliest references to him in the press and to his first cartoon heroine. In 1924, the Los Angeles Times allotted only a few lines of space on a back page to a brief mention of ‘a young cartoonist by the name of Walt Disney’ who was ‘making a series of twelve animated cartoon productions’ about a girl named Alice.6 These were Disney’s Alice in Cartoonland films that mixed live action with animation, and that drew, of course, on Lewis Carroll’s nineteenth-century fairy tale, just as, later, Disney would adapt the fairy-tale sources – the Brothers Grimm most prominently – for Snow White.

Walt Disney shows Alice a drawing that has come to life, in Alice’s Wonderland, from 1923

After Alice, Disney’s fame and reputation increased dramatically, of course, with the introduction of Mickey Mouse. His studio’s early and complete commitment to the new sound technology of the late 1920s, and Disney’s determination in this early period to make music a fundamental aspect of all of his cartoons, made critics and the public take notice. Industrial imperatives also helped, as the unceasing demand from the country’s 20,000 or so cinemas for product – from features to live-action shorts to newsreels to cartoons – provided a speciality studio like Disney with steady outlets for its animated short subjects.

Disney’s rise began, tentatively enough, with Steamboat Willie, the second Mickey Mouse cartoon, but also the film that signalled the studio’s conversion to sound. When the film premiered in New York in 1928, paired with a now forgotten feature film called Gang War, the critic for The New York Times noted it as ‘the first sound cartoon’, and identified the producer, quite formally, as ‘Walter Disney’, reminding readers that he had become known for a previous series of animated shorts starring Oswald the Rabbit.7 Just one year later, Disney was admired as both innovator and artist, at the forefront of mixing sound with image. When his newest Silly Symphony cartoon, Springtime, played at the lavish Grauman’s Chinese Theater in Hollywood (appearing just after the widely acclaimed Skeleton Dance), the Los Angeles Times proclaimed that ‘Imagination in picture-making has at no time been more strikingly disclosed than in the Walt Disney comic currently’ showing.8 In the months to follow, the fame of the producer and an assumption about the quality of his product became universally accepted. In April 1931, to cite just one example among many, the leading French film magazine Pour Vous acknowledged Disney’s greatness and then lamented France’s own apparent lack of an animated film industry, asking, ‘Will we have our own … Mickey any time soon?’9

Mickey Mouse plays a washboard in Steamboat Willie (1928)

At the time of this developing reputation, Disney produced cartoons with assembly-line regularity: 19 animated shorts in 1930, 22 in 1931 and 1932, then another 19 in 1933. These films were distributed to exhibitors in two series, the Silly Symphonies and the Mickey Mouse cartoons, in fairly even numbers. Disney more or less maintained these production schedules even as his studio shifted much of its emphasis to feature films in the mid- to late 1930s. In 1937, the year the studio completed Snow White, Disney produced fourteen cartoon shorts, made up of the Mickey Mouse films, one Donald Duck (Donald’s Ostrich) and the Silly Symphonies. It was the films of this latter series that most anticipated Snow White. Like all Disney films of the time, the Symphonies were made in Technicolor and emphasised sophisticated musical scores, while many of them, for instance the much-heralded The Old Mill (1937), sought to establish mood and tone as well as narrative, much in the manner of Snow White.

Interestingly enough, this regular supply of product and the early adoption of sound, as much as the subject matter of the films, helped make Disney an icon of modernity in the eyes of the emerging American avant-gardes in the 1920s and 30s. The various experimental art groups, from the editors of the short-lived literary magazine The Soil (1916–18) to the more acclaimed Dadaists, celebrated the apparent challenges to high art posed not only by photographers such as Paul Strand and such ‘Ashcan’ painters as George Bellows, but also by Disney and Mickey Mouse. They extolled the highly technologised production of so much popular culture, and especially the labour-intensive, mechanised animated films of the period.10 The Silly Symphonies in particular, however, delivered middlebrow refinement rather than avant-garde pleasures to film audiences, and critics, intellectuals and various reform groups, so rarely speaking with one voice at the time, praised them as perfect entertainment for all viewers.

This endorsement of Disney’s universal appeal situated the cartoon producer on the ‘correct’ side of significant debates about cinema that took place during the 1930s. As a means of dealing with protests from parents’ and teachers’ organisations, religious groups and others mobilising against movies, the major studios had begun to assert more fully the literary and historical worthiness of their product; hence the production of films such as Little Women (RKO, 1933), The Barretts of Wimpole Street (MGM, 1934), Romeo and Juliet (MGM, 1936) and The Story of Louis Pasteur (Warner Bros., 1938). While film historians have written for at least the last decade about this attempt to prove the high-mindedness of American cinema, one of the more little-known conflicts of the period concerned the perception of a demographic divide in movie tastes. In particular, residents in small towns often felt that Hollywood made films for big cities such as New York, Los Angeles and Chicago, with a sensibility geared towards more urban audiences. Walt Disney, along with Frank Capra and a few other film-makers, was among a very small group of men who were considered capable of providing films that might be considered both cosmopolitan and rural. At the same time, even though Hollywood assumed that all audiences should be able to see and enjoy all films, many viewers and critics recognised that the studios produced movies for very specific age groups and made very few films for the entire family. Thus, all of the Mickey Mouse films and Silly Symphonies set a precedent and established the formula for a movie like Snow White, which would emerge as something of a perfect Hollywood product: one that demonstrated the movie industry’s commitment to a kind of literary high quality, and as a film that could be enjoyed by sophisticated and also less worldly audiences, by children as well as adults, by city audiences and those in small towns.

Throughout the period of Disney’s ascendance, Hollywood’s production, marketing and exhibition methods received ample criticism from parents’ and teachers’ groups, psychologists, intellectuals and others. In 1939, sociologist Margaret Farrand Thorp, in one of the founding volumes of modern film studies, America at the Movies, went so far as to claim that viewers lacked all agency and free will even when it came to deciding which movie to see on a given night. Farrand was a film enthusiast and defender of popular culture, but she wrote ominously that the choice of film ‘was predestined months ago, predestined by forces working so steadily and so subtly that the chooser is usually quite unaware how he got it fixed in his mind that The Life of Mr Blank is a film he really ought to see’.11 But at least during the 1930s, critics placed Disney and very few other film-makers in a different category from other members of the studio system, and well beyond the ceaseless cookie-cutter of the studio assembly line. As Thorp also wrote, ‘The pearl of great price’ in the film industry ‘is the picture that pleases everybody’, adding that ‘So far, just two pearls have been found: Charlie Chaplin and Walt Disney.’ Commenting on Disney’s most recent film and his most famous character, she claimed that ‘On Snow White and Mickey Mouse it is scarcely possible to find a dissenting’ critical voice.12

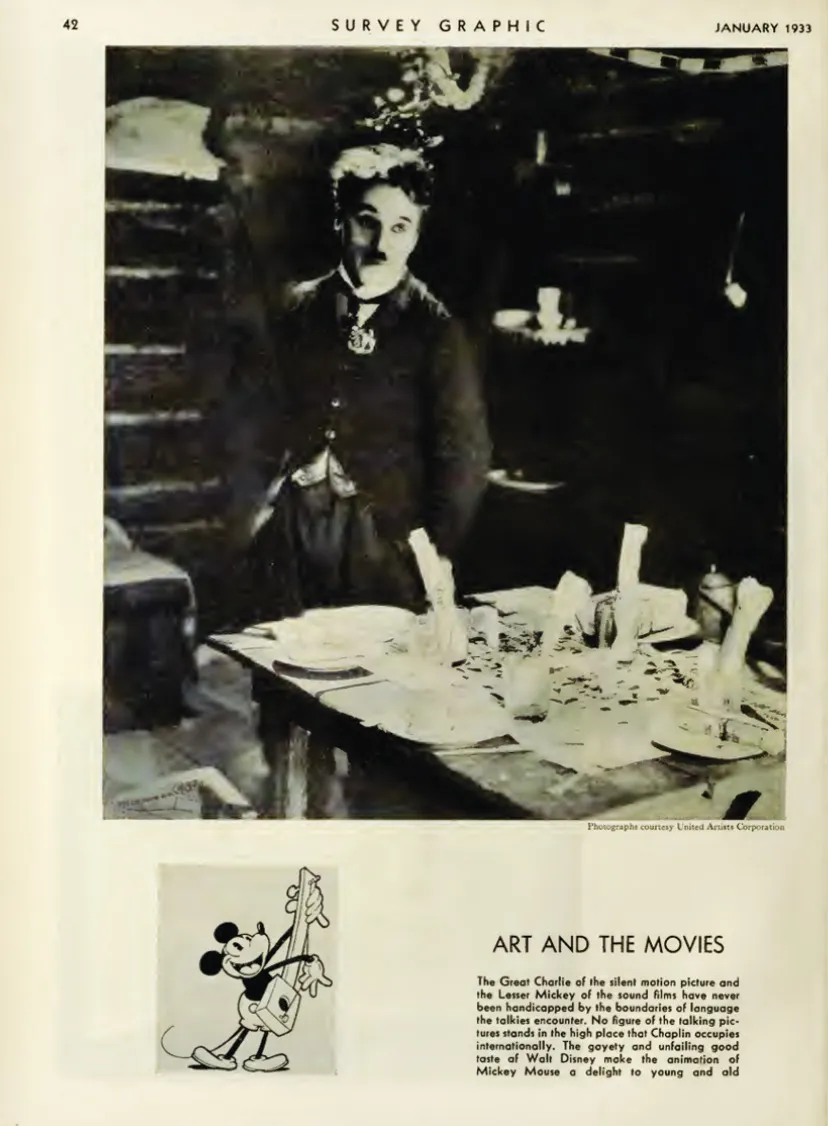

The comparisons to Chaplin had been commonplace for years. As early as January 1933, just five years after Mickey Mouse’s debut but almost two decades after the Little Tramp’s, the Survey Graphic magazine examined ‘recent trends in the arts’.13 The Graphic was one of the significant middle- to highbrow publications of the period, commenting with authority on issues of political and cultural importance (in 1925, for instance, it famously coined the term ‘New Negro’ in its special issue on Harlem). Discussing the art scene in 1933, the magazine wondered about the impact of ‘mass production and modern distribution’, while celebrating advances in interior design by William Lescaze, furniture by Silvia Van Rensselaer, the new boxes used by the Western Clock Company and packages for pharmaceutical products. For a section on ‘Art and the Movies’, the Graphic supplied only two examples: Chaplin and Mickey Mouse, ‘the Great Charlie … and the Lesser Mickey’. For the Graphic, Disney was part of the best of modernity, and his production methods, while on a large scale, still resulted in a cultural form that was humane, accessible and original. The studio stood as a sign of the interrelatedness of art and commerce in the twentieth century, just as much as those exquisite living rooms and clock boxes, and was practically on a par with Chaplin, the greatest artist of the cinema.

In January 1933, Survey Graphic held up Charlie Chaplin and Mickey Mouse as proof that movies might produce art

At about the same time as this assessment in the Graphic, Disney expanded his production capacity by moving aggressively into merchandise connected to his movies. He began licensing his characters, and particularly Mickey Mouse, becoming the first filmmaker to exploit the merchandise market systematically, something that would, of course, prove to be an even greater bonanza with Snow White and the ubiquitous Dopey dolls and other knick-knacks. But even by 1934, Mickey Mouse watches and pencil sets and dial phones were everywhere, and especially in major department stores. Just as his film production methods made him a hero of modernity without eliciting any of the complaints that so often accompanied the Hollywood assembly line, so too did his film-related goods avoid the criticism that, at the time, was usually directed at any plan that sought to turn children into consumers. As Richard deCordova has pointed out, Disney’s 1930s department store products indicated the animator’s value as an educator of children, rather than as someone who exploited kids’ desires to possess those things that were connected to the cartoons they saw in cinemas.14

In fact, Disney’s spotless reputation only grew during this per...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Preface

- 1. Pre-History

- 2. Production

- 3. The Film

- 4. The Response

- 5. Afterlife

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Credits

- Bibliography

- eCopyright