![]()

Part 1

![]()

1.1 Artists

The Film Society: Little Magazines: Internationalism and Festivals: Schooling Artists: The London Filmmakers Co-op: Into the Gallery: Video as Video: The 1990s

THE FILM SOCIETY

Film-making by artists in Britain began in the second half of the 1920s and, as with many such creative bursts, coincided with a period of intense speculation about the future of the art form. In the last years of silent cinema, the commercial studios of France, Germany and Denmark had produced feature films that were highly individual, strongly visual and bore the mark of their individual authors – simultaneously expanding the language of commercial narrative film, and laying the foundations of today’s ‘art cinema’. But new technological developments, such as full-colour film stocks and reliable sound film technologies, seemed to change the nature of film radically, upsetting past certainties. And commercial film-makers throughout Europe were becoming anxious about the growing domination of production from the USA.

In London, the Film Society1 (1925–39) provided a space for viewing new films and encouraged debate about cinema. Its once-a-month screenings were run by a group of intellectuals from many different disciplines – film, literature, the visual arts – initially brought together by the desire to see foreign films, and the need to circumvent Britain’s cumbersome censorship and film licensing laws. Adrian Brunel and Ivor Montagu, both working at the fringes of the film industry, were two of the Society’s founders, and while artists such as the sculptor Frank Dobson, the painter/writer Roger Fry, the designer E. McKnight Kauffer, and the illustrator Edmund Dulac constituted a small minority among its members, they were none the less essential to its mix. The breadth of members’ professional interests was matched by the eclecticism of the Society’s programming. Typical of what was to follow, its first programme of 25 October 1925 included the wholly abstract animations Opus 2-3-4 (1923–5) by the German painter and later documentary maker Walther Ruttmann, the comedies How Bronco Billy Left Bear Country (Essanay USA c. 1915), Champion Charlie (Chaplin / Essanay 1916), Brunel’s ‘burlesque’ Topical Budget (1925), and Paul Leni’s expressionist feature film Waxworks (Germany 1924). Programmes regularly featured episodes from Mary Field and Percy Smith’s popular natural history series Secrets of Nature, reflecting Montagu’s training as a zoologist and interest in scientific film, and might include demonstrations of new colour processes and sound-film systems, designed to be of interest to film industry members such as David Lean, Michael Powell and Alfred Hitchcock, and experimentalists alike.2 Oskar Fischinger’s Experiments in Hand Drawn Sound (aka Ornament Sound 1932) were shown together with Laszlo Moholy-Nagy’s similar translation of images into sounds A B C in Sound (1933). Silent feature films were usually accompanied by a full orchestra, but even the problem of sound could be approached experimentally. Jack Ellitt, a modernist composer who was also Len Lye’s preferred sound editor, provided ‘non-synchronous’ musical accompaniments to silent films for the Society throughout the 1934–5 season.

3 The logo designed by E. McKnight Kauffer, spliced onto all film-prints shown by The Film Society.

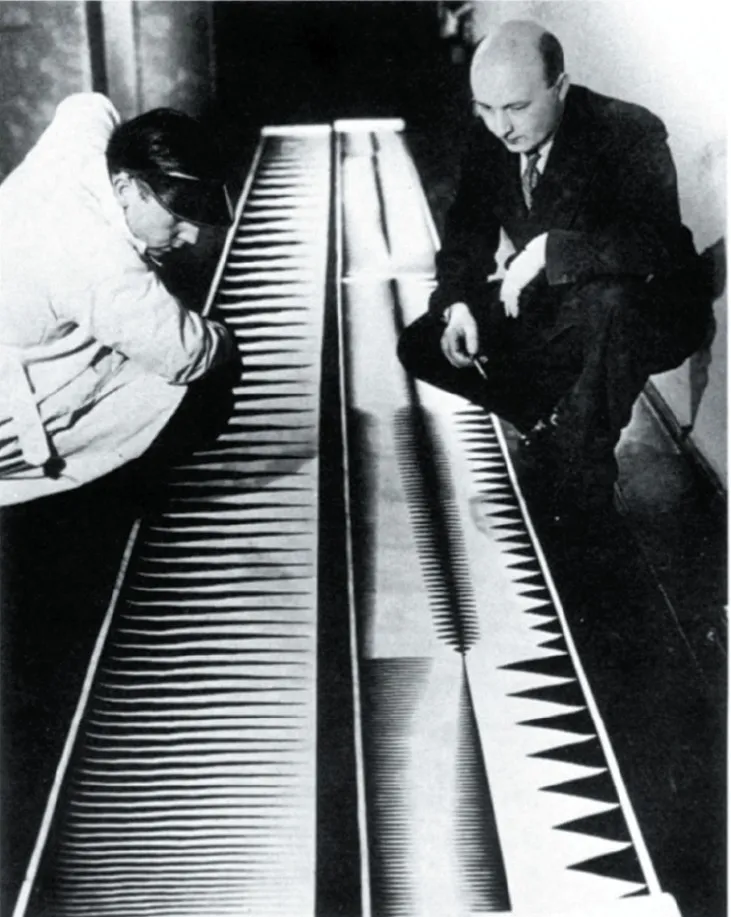

4 Oskar Fischinger ‘at work’ on his Experiments in Hand Drawn Sound (a staged publicity photo), Germany, 1928.

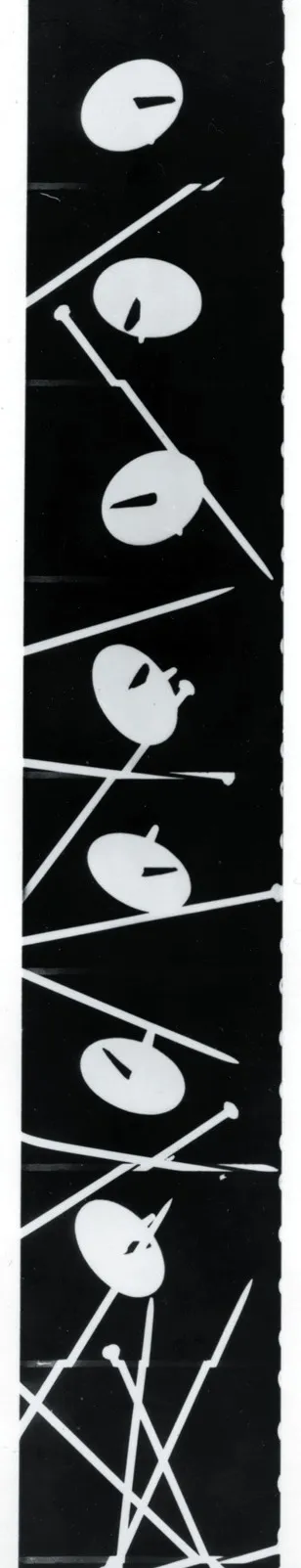

5 ‘Rayogrammed’ strip from Le Retour à la Raison, Man Ray, France, 1923.

The Society made it possible for artists to see the work of their film-making contemporaries abroad. It staged the first English screenings of Rene Clair’s Entr’acte (France 1924), Fernand Léger’s Le Ballet mécanique (France 1924), and works by Sergei Eisenstein, Man Ray, Marcel Duchamp, Germaine Dulac, Charles Scheeler and Paul Strand, Dziga Vertov, and many others, where possible introduced by their makers. In addition to Brunel and Montagu, British artists and experimenters who exhibited at the Society included Len Lye, John Grierson, Oswell Blakeston, Francis Bruguiere, Kenneth Macpherson, Desmond Dickinson, Alberto Cavalcanti, Humphrey Jennings, the partnership of Anthony Gross and Hector Hoppin, and many others. The formal style of the Society’s programme notes, which refer to directors and technicians alike by their titles (‘Mr Richter’ etc.), evokes screenings received in respectful silence, but Montagu reports this was not always the case. Entr’acte appropriately provoked a near riot:

cries and catcalls rang out, pundits within the audience came within an ace of punching each other. Frank Dobson was sitting near Clive Bell, whose excitement was fever pitch in defence of what he regarded as an unjustly denigrated opus of genius, Dobson murmured pensively afterwards: ‘Makes one [wonder] what they say of one’s own work, doesn’t it’.3

6 The Film Society ‘workshop’ group; with Richter (left) Eisenstein (with policeman’s helmet), Jimmy Rogers at the camera, Basil Wright (glasses and cigarette), Len Lye (extreme right, seated) and others.

While it encouraged interest in film-making, the Society held back from direct involvement in film production. However in 1929 it invited the German painter/film-maker Hans Richter to direct an experimental film-making workshop to accompany a lecture series given by Eisenstein. The workshop was held in an attic above Foyles bookshop in Charing Cross Road, and attended by (among many others) Eisenstein, Lye, and a young Basil Wright.4 But the Society’s focus remained firmly on exhibition and, almost by default, on distribution, as other societies and even commercial cinemas sought to show works that the Society had imported. The significance of the Society to Britain’s emerging film avant-garde was its function as a venue for showing work, and the promise it extended of a critical response from a group of interested peers. In this the Society acted as a role model for many similar groups throughout Europe and America.

Politically inspired film-makers of the period had even greater reason to form groups in order to get their films seen while avoiding censorship. Kenneth Macpherson and Henry Dobb, the film critic of the left newspaper The Sunday Worker, had proposed a scheme to enable workers’ groups to see important films at a price they could afford. After a legal struggle with local authorities which seemed determined that the privileges of a film society should be restricted to the wealthier middle-classes, this was effectively realised by Ralph Bond and others with the setting up of the Federation of Workers’ Film Societies in 1929. A national distribution organisation Kino followed in 1934. The Federation brought together the interests of making and exhibiting groups such as the Socialist Film Council, the London Workers Film Group, and the Workers’ Film and Photo League (itself an association of amateur groups). Montagu left the Film Society to set up the Progressive Film Institute (its name a dig at the recently founded and strenuously apolitical British Film Institute), which was to engage directly in political film-making, and to distributed films such as Eisenstein’s Potemkin to leftist groups. The Depression of the early 1930s, the rise of Fascism in Europe and the Spanish Civil War were reflected in the theme of films such as Bread (1934) made by the Workers’ Theatre Movement, Montagu’s Defence of Madrid (1937), made with animator Norman McLaren as cameraman, and his Peace and Plenty (1939).5

7 Peace and Plenty, Ivor Montagu with Norman McLaren, 1939.

LITTLE MAGAZINES

Film’s potential was debated in a growing body of critical writing in the 1920s and 1930s. Films screened at the Film Society and its more political counterparts were reviewed by the commercial film press with a mix of interest and suspicion. The Film Society’s founding coincided with, and contributed to, the beginnings of serious film journalism, and many Society regulars were also journalists in positions of influence. Iris Barry, another founder member, became a prominent film journalist in the 1920s, and established the role of film critic at the Daily Mail. Montagu was the first film critic of The Observer and The New Statesman. And reviews appeared in unexpected contexts such as the Architectural Review, where Oswell Blakeston discussed ‘Len Lye’s Visuals’, and previewed his own film made with Francis Bruguiere, Light Rhythms (1930).6

More important to the development of an active film-making culture were the debates generated in specialist film magazines. Of these, Close Up (1927–33) and Film Art (1933–37) were the most significant, though Robert Herring’s literary magazine Life and Letters Today (1928–50) also made an important contribution. Close Up was edited by Kenneth Macpherson from Kenwin, a modernist pavilion at Riant Chateau in Territet, Switzerland, built by his partner Bryher (Annie Winifred Ellerman, heiress to a shipping fortune). This artistic pair together with the poet HD (Hilda Doolittle) formed Pool Films to produced three short films credited to Macpherson, and the feature-...