- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

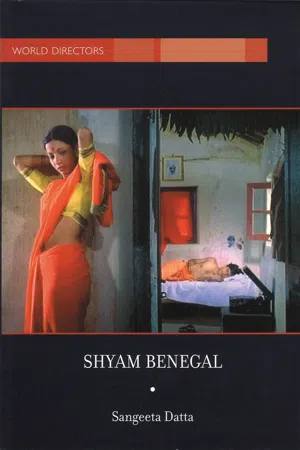

Shyam Benegal

About this book

Shyam Benegal is the best known and most prolific contemporary film-maker from India's arthouse or 'New Cinema' tradition. This work traces a career with its beginnings in political cinema and a realist aesthetic. Sangeeta Datta demonstrates how the struggles of women and the dispossessed and marginalised in Indian society have found an eloquent expression in films as diverse as Nishant, Bhumika, Mandi, Suraj Ka Satwan Ghoda and Kalyug. The book also traces Benegal's work with his protégés and collaborators including many of the biggest names in Indian Cinema - Shabana Azmi, Smita Patil, Naseeruddin Shah, Karishma Kapoor and A.R. Rahman.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Shyam Benegal by Sangeeta Datta in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

One

Parallel Cinema in India

The work of Benegal is central to the history of Indian alternative cinema. This cinema has many names, including new cinema, Indian new wave, parallel cinema, realist cinema and even regional cinema, and there are good cases for using any and all of these terms. While in many respects I prefer to use the term ‘parallel cinema’, I shall also below refer to the movement as ‘new cinema’, which as a term captures some of the freshness and the excitement of a new development in the immediate postcolonial context of the 1950s.

Just how useful are these labels of ‘new’ or ‘parallel’ cinema anyway? These are categories that somehow embrace a diversity of film-makers, techniques, approaches, aims and intentions. Many consider Satyajit Ray to be the pioneer of this school, the history of which dates back to the 1950s. If we consider the 1960s, then film-makers as diverse as Mrinal Sen, Ritwik Ghatak and Mani Kaul – with their differing ideologies, views and structures – would need to be accommodated.

A defining relationship is that of the movement’s position in relation to the commercial cinema industry. Whereas the terms ‘new’ and ‘alternative’ serve to underline divergences from popular cinema, the term ‘parallel’ cinema instead suggests a genre of cinema which runs alongsidethe mainstream. It has been argued that the sensibility and ideology of the educated and trained film-maker drove this parallel cinema, reaching out to a liberal middle-class viewer who shares his or her progressive notions. To the commercial film-maker, such notions of cinema are elitist. This is borne out further by comments from film critics such as Chidananda Dasgupta, who affirms:

The difference between art cinema and commercial cinema in India is simply the difference between good cinema and bad – between serious films and degenerate ‘entertainment’. The new cinema in India is a creation of an intellectual elite that is keenly aware of the human condition in India.1

Such arguments have only served to underscore the high art versus popular culture debate and polarise it further. By describing popular cinema as the slum’s eye view of national politics, Ashish Nandy has reinforced the same oppositional discourse of high art and mass culture.2 The success of some of Benegal’s films (e.g. Ankur) does, however, suggest a more complicated picture than this and a more complex interaction with audiences than the elitist–populist debate suggests. Likewise, the production histories of a number of the films (sponsored in part or in whole by cooperatives or other collective bodies) also testify to a fuller engagement with non–middle-class communities on the part of the film-makers than critics allow. Lastly, the impact of parallel cinema aesthetics on the mainstream suggests a legacy of mutual influence alongside a history of contrast.

These categories and their counterparts of ‘popular’, or ‘mainstream’, or ‘Bollywood’, cinema are anything but watertight. In practice parallel and mainstream cinema have overlapped and intertwined in response to the same changing social contexts from the 1950s to the present.

Indian cinema as an institution

When India gained independence soon after World War II in 1947, the war had already affected both the economy and the format of popular cinema in India. The breakdown of the three influential studio production companies, Bombay Talkies, Prabhat and New Theatres, marked a shift in ideology away from the reformist zeal that characterised cinema of the 1930s and early 1940s. One example of that zeal had been Achut Kanya (Prabhat, 1936), while other films such as Mukti (New Theatres, 1937) addressed the conflict between changing social values. By 1947, however, postwar profiteers had turned into fly-by-night producers, and the market was awash with unaccounted money. This economy fuelled the star system by offering unprecedented amounts of money to stars. By the 1950s, films were sold by the dominant stars of the time, not by production banners. Against this background, film-makers such as V. Shantaram, Mehboob Khan, Bimal Roy and Guru Dutt who worked in mainstream cinema still continued to explore relevant social issues in their works. Mehboob’s Aurat, later reworked as Mother India (1957), and Bimal Roy’s Sujata and Bandini were particularly significant in exploring the ideology of womanhood and creating strong, individual female characters.

The S. K. Patil Film Enquiry Committee submitted its report in 1951. Commenting on all aspects of cinema, it noted the shift from the studio system to individual entrepreneurship. Strongly critical of the black market and the star system, the report recommended state investment in film production and the setting up of a film institute and film archives. These proposals were supported by some film-makers critical of popular cinema who foregrounded the aesthetics of film or used the cinematic form for social comment. During this time, there was a concerted effort by the state to institutionalise cinema. Soon after Nehru formed his government in 1952, the first International Film Festival of India was held in Bombay, Madras and Calcutta by the Films Division. For the first time, the Indian film industry had an opportunity to watch a large number of films from across the world. The films of Vittorio De Sica made a tremendous impact, and neo-realism had a lasting influence on Indian film-makers. The same year, Indian film industry representatives visited Hollywood at the invitation of the Motion Picture Association of America.

International recognition of Indian cinema then began to gather pace. In 1953, Bimal Roy’s Do Bigha Zameen (Two Acres of Land), showing the direct influence of Italian neo-realism, received a special mention at Cannes and the Social Progress award at the Karlovy Vary Festival. In 1954, the first national film awards were instituted, and P. K. Atre’s Marathi feature Shyamchi Aai (1953) was awarded the best feature film. The same year, Raj Kapoor’s Awaara (1951) proved a major hit in the Soviet Union. Prior to this, the socialist Indian People’s Theatre Association’s film Dharti Ke Lal (1946) had received widespread distribution in the Soviet Union in 1949.

In 1955, Satyajit Ray’s Pather Panchali (The Song of the Road) was released, triggering Ray’s international success. It was premiered at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. In 1959, the film ran for seven weeks at the Fifth Avenue Playhouse, New York, breaking a 30-year record for foreign films in the United States.3 Ray’s film showed the influence of neo-realism in his use of outdoor locale, available light and amateur actors. The Bengali-language film made under considerable financial constraints finally generated money for the West Bengal Government. Its economic success persuaded the central government to review the Film Committee recommendations of 1951, which it had so far ignored.

In 1955, Nehru made his famous speech at the Avadhi Congress calling for a ‘Socialistic pattern of society’. This formed the basis of what came to be defined as the ‘Nehruvian’ vision of the secular state, citizenship, egalitarianism, education and technological progress. Nehru’s focus on children as the ‘future of the nation’ worked as a potent metaphor for the optimism of a young nation. The Children’s Film Society was set up in the same year to target young audiences. Later, Benegal was to make his children’s film Charandas Chor (1975) for this society. His prodigious work in the documentary field testified to his version of Nehruvian idealism.

By 1956, Indian films were being showcased at various international forums, such as the Edinburgh, Karlovy Vary and Berlin film festivals. Ray’s Aparajito (Unvanquished, 1956) won the Golden Lion at Venice, and Sombhu Mitra’s Jagte Raho (1956) won the first prize at Karlovy Vary in 1957. The first Indo-Soviet co-production, Pardesi (co-directed by K. A. Abbas and Vassili M. Pronin), was made the same year. Ritwik Ghatak’s Ajantrik (1957) was shown at Cannes in 1958.

The Federation of Film Societies was founded in 1959, with Satyajit Ray as president. Twelve years prior to that, Ray had launched the Calcutta Film Society along with critic Chidananda Dasgupta and other friends. This launched a national network, operating on a moderate scale even today, which provided access to world cinema and a forum for debate for enthusiasts in cities and small towns.

‘Times of great ferment …’

Within the same period (1950–70), the new democracy also busied itself in the business of nation building. Left-led peasant movements in Kerala, Andhra Pradesh and Bengal; student uprisings (the Naxalite movement) in Calcutta; border conflicts with Pakistan and China; riots and conflicts around state reorganisation; the North–South language and culture debate; acute food shortages leading to grain importation from America – these were some of the strongest challenges to the new nation. In keeping with the Nehruvian socialist and secular vision, progress was constructed through structured planning (five-year plans), technological advances (iron and steel plants, dams which were hailed by Nehru as temples of the future), and a celebration of regional diversity and didacticism through educational programmes on radio and television. The official attempt was to construct an image of integrated India progressing towards modern times. A nation in transition, however, manifested its discontents in conflicts and ruptures which belied the promise of this idea of India.4

By the late 1960s, there was political upheaval across the country, particularly in the East and Southeast. In 1967, widespread armed peasant insurgency in the Naxalbari district of Bengal grew against the landlords. The Naxalite rebellion took a new turn in 1970 with student uprisings in Calcutta. Corruption in education, unemployment and the class divide were all leading to the collapse of the democratic dream. In some Naxalite pockets in the state of Andhra Pradesh, peasants redistributed land among themselves. Protest against feudal structures, caste, class and community divides was becoming increasingly strident. As Benegal himself puts it, ‘Those were times of great ferment … I was deeply influenced by the peasant struggle.’ The Indo-Pakistan War in 1971 resulted in the liberation of East Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh. New cinema was therefore born in the immediate context of political strife and protest.

Benegal among the weaver community in a village in Andhra Pradesh shooting Susman

Benegal with cinematographer V. K. Murthy on location for Antarnaad. Local villagers form part of the cast

Against this gradually unfolding context, the government implemented the 1951 Film Committee recommendations and, in 1960, started the Film Finance Corporation (FFC) to give low-interest loans to selected projects. The FFC was modelled on Britain’s National Film Finance Corporation, offering funds for quality films. In 1960, the National Film Institute was founded in Pune on the former Prabhat Studio premises. Professionally trained actors and technicians were to be made available to the industry for the first time. Students gained access to a wide range of world cinema. Film-maker Ritwik Ghatak took on the directorship. His students included K. K. Mahajan, Mani Kaul and Kumar Shahani, who later became influential film-makers in their own right. The same year, the Institute for Film Technology was set up in Madras.

Government-sponsored cinema was to create a new tradition. Supported heavily by film critics in the press, this movement privileged cinema as an art form and declared realism as its manifesto. The movement was born with inherent contradictions: it had to be specific and particular in its code of realism and yet universal enough to appeal to a wider audience outside the country while also being entertaining enough to reach the Indian masses. The Indian Motion Picture Export Corporation (IMPEC) was formed in 1963. A manifesto for an Indian new cinema movement was issued by Mrinal Sen and Arun Kaul in 1963, advocating a state-sponsored cinema for new directors.

In the 1960s, popular cinema was preoccupied with romance, family structures and the nuances of urban–rural values. In this context, Mrinal Sen’s iconoclastic Bhuvan Shome (financed by the FFC) may be said to have launched the Indian new cinema in 1969. The unusual theme (a railway bureaucrat enters a simple village girl’s life) and the treatment set up an ironic conflict between city/village sensibilities. Although Ray’s Bengali films were already popular in the West, they were far less well known in Indian regions outside Bengal. And Bhuvan Shome made a big impact just as innovations in Bengali cinema by directors such as Ray, Ghatak and Sen were brought to the Hindi-speaking, pan-Indian audience for the first time. Equally significant were Mani ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Other Titles in the Series

- Title page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1. Parallel Cinema in India

- 2. The Formative Years

- 3. The Rural Trilogy: Winds of Change

- 4. The Woman’s Voice: Bhumika and Mandi

- 5. Histories and Epics

- 6. Subaltern Voices

- 7. The Last Trilogy: Search for Identity

- 8. Experiments with Truth

- Appendix: Reflections

- Notes

- Bibliography

- Filmography

- Index

- eCopyright