eBook - ePub

Salo

About this book

Beneath the extreme, taboo-breaking surface of 'Salo' (a controversial and scandalous film made in 1975), Gary Indiana argues that there's a deeply penetrating account of human behaviour which resonates as an account of fascism and as a picture of the corporate world we live in. 'Salo' was Pier Pasolini's last film (he was murdered shortly after completing it). An adaptation of Sade's vicious masterpiece, it is an unflinching, violent portrayal of sexual cruelty which many find too disturbing to watch.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Salò

1

I was twenty-seven when I first saw Pasolini’s Salò. I worked nights at the popcorn concession of the Westland Twins, a Laemmle theatre in Westwood specialising in foreign films of the ‘mature romance’ variety. A friend managed The Pico, an art cinema in the Fairfax District. It was autumn, 1977. I got off work at 10.30. I usually drove home to Los Angeles, stopping at The Pico, where Salò ran that season as a midnight movie. (Actually, I think it was an eleven o’clock midnight movie.) That’s how I happened to see this film, or parts of it, almost every night for two months.

I have a terribly spotty memory. This has served me pretty well as a writer, since I have to fill the yawning gaps between what I truly remember with whatever my imagination suggests ‘must have happened’. I remember that melancholy period of my life in time-stained flickers, a slide show of faces and landscapes across a paling light. I was twenty-seven, but I think of myself then as ‘pre-conscious’. The world was just beginning to emerge as something separate from the muck of my private anxieties. I went to the movies all the time. I believed that the emotions projected in films and dramatised in popular songs were the same emotions I had. I felt tremendous nostalgia for a history I didn’t possess, for loves I’d never experienced, for bitter lessons I’d never learned.

One of the few places where you could get a drink after a certain hour was a Silver Lake bar called The Headquarters, an S&M club where police impersonators in uniform mingled with dowdier slaves and masters in dog collars and trouserless chaps. (Leather had had its major effulgence much earlier in Los Angeles, celebrated in the classic fistfucking porno, LA Plays Itself, and in movies by Wakefield Poole. By the late 70s the hardcore raunch scene was more happening in New York and San Francisco.) There were also the One Way, The Detour, The Spike, a constellation of more conventional gay bars at the nether end of East Hollywood. The punk scene was in full mood swing. One of the only boutiques on now-famous Melrose Avenue was a tiny storefront called Tokyo Rose, where you could buy pre-ripped T-shirts festooned with safety pins.

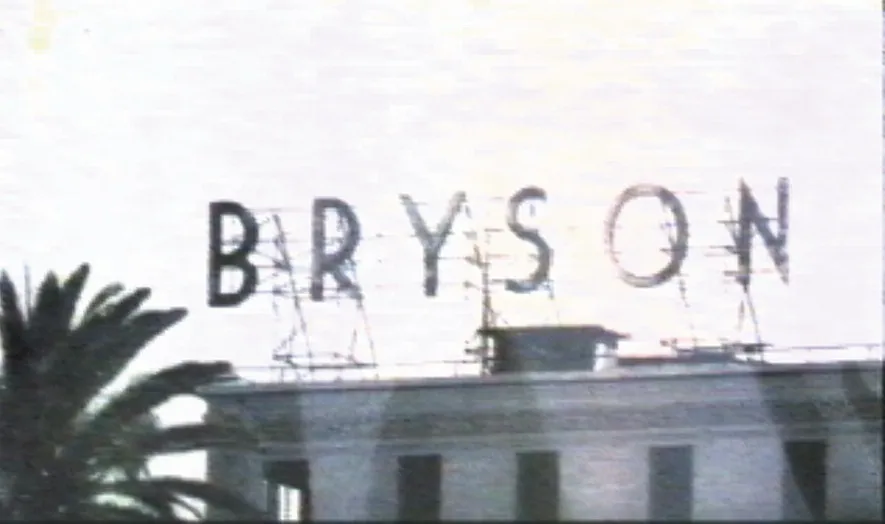

During the day, I worked at Legal Aid in Watts. A dispiriting job. I dealt with seriously damaged, desperately poor people who lived in rotting bungalows where rats routinely fell through crumbling ceilings into their breakfast cereal. I lived in a somewhat sinister apartment hotel on Wilshire (The Bryson, where Stephen Frears shot The Grifters many years later, simulating its mid-70s desuetude – when I lived there, Fred MacMurray was the silent partner in the building’s ownership) full of insomniacs, drifters, madmen, a kind of Chelsea West: the night clerk was a preoperative transsexual named Stephanie.

It was a time of compulsive, almost mechanical sleeping around that felt good for a few moments here and there. I had two jobs, and about two hours at the end of the night to pick someone up in a bar. Whatever followed that took at least two more hours, depending on the drive time, so I suppose in that faraway autumn of 1977 I got an average of three hours sleep a night. That was my life, and Salò became for two months a logical part of it, another little patch of soft, crumbly alienation and waking dream.

The Bryson, the haunted castle of my youth, reconstituted in The Grifters

2

The Pico is long gone, The Bryson is currently draped in scaffolding and sandblasting paraphernalia, and soon will become a warren of pricey condominiums. (Since writing this line, the drapery has vanished. By the time you read this, the empty units will be full.) And the plangent backwater atmosphere of Los Angeles in the 70s is long gone, too, replaced by a horror vacui of gentrification and millions more motor vehicles, the most egregious being tank-scale SUVs piloted by small, angry, recently divorced women who launch their own private Chechnya into traffic whenever they leave the house.

I don’t propose to endlessly revisit my first encounters with Salò, or fold them into an autobiography, but I do want to ‘personalise’ it at the outset, before proceeding with an unavoidable flurry of notes on Pasolini, movies and shifts in the cultural temperature from one period to the next – notes, I should add, that will probably not win me any friends among film scholars or Pasolini experts. I am not fluent in Italian, so there are myriad nuances in Pasolini’s work that I can neither perceive nor contextualise. I no longer live immersed in movies as I once did, and I confess that much of what I found wonderful twenty or thirty years ago no longer holds much interest for me. Re-viewing all of Pasolini’s films after many years, I found that I could only revisit my affection for some of them through an effort of somewhat dubious nostalgia, by ‘remembering the 60s’ (I saw most of Pasolini’s movies, though obviously not this one, in the 60s) and the chaos of a completely different cultural moment. On the other hand, films that I hadn’t cared much about when I first saw them – Notes for an African Oresteia, Oedipus Rex – now impressed me as truly uncanny works of cinematic poetry.

It’s tricky to consider one of Pasolini’s films in isolation, because he occupies so much space as a figure. At the same time, the energy that collects around big, imposing names in the cultural suet deserves a measure of scepticism. Once artists become monuments, the required way of regarding them is almost absurdly contrary to our way of regarding anything else. We are obliged to find worlds of meaning in every scrap of paper they might have doodled on, any material sign of their existence turns into manna. The resulting industry of preservation, worthy as it is, has the paradoxical effect of killing any spontaneous encounter with their work. Are we genuinely moved by Mozart’s music, or are we moved because we know that Mozart’s music is moving? Is the publication of Kafka’s Blue Notebooks a revelation, or evidence that not everything an artist does is worth preserving?

3

Pasolini’s total body of work is a vast, erratic sprawl of things – essays, poems, novels, newspaper columns, paintings, drawings, films, and I hate to think what else. As one of perhaps two dozen directors doing unusual ‘personal’ movies in the 60s and 70s, he was part of a heterodox, liberating wave, someone whose films could be welcomed as elements of a wide-ranging spirit of revolt. In their temporal setting, they didn’t need to be closely understood or analysed to be appreciated.

As a young American viewer, I only understood Pasolini’s films to be about things that weren’t explored in American movies. They were quirky and subversive of narrative expectations, informed by a highly eccentric reading of Marx and Freud. Like Godard’s films, they approached storytelling in a completely idiosyncratic way, they dared to look amateurish and indulged in all sorts of obvious fetishism. The camera eye in Pasolini’s films conveyed a blatant sexual interest in his male actors, of a whole different order than the Hollywood truism that ‘a movie star is somebody a lot of people want to fuck’. Erotic interest in the male body was still elaborately dissembled in most movies, coded, deflected by heterosexual love stories and exploitation of the female body. Pasolini’s films were coded, too, but not coded enough for the subtext to be at all ambiguous. At the same time, at least part of what I liked about Pasolini’s movies, back then, was their opacity. (One thing people tend to forget about the 60s – which ended in one sense in 1969, but in another sense around 1975 – is how grossly inarticulate all the hip people really were. A small number of expressions were used to say everything. No one had to explain in real language what they understood about anything; if they tried, they were likely to reveal an incredible poverty of thought. Teorema was ‘far out’. Beginning and end of discussion.)

Two and a half decades after his death, Pasolini has the sacred aura of a ‘figure’, an object of research, a dessicated collection of ‘meanings’. To talk about Salò, I want to avoid any too-technical interrogation of Pasolini’s methodology, and not fall into the trap of assuming that his intentions are entirely realised in his work, or that Salò needs to be viewed through the scrim of his other films, his poetry, his novels, etc. Everything he did does not hold equal interest. Travelling exhibitions of his pleasant, unexceptional paintings don’t enhance the experience of his films. They burnish the cult of the proper name, add volume to the idea of ‘genius’ that so often makes the experience of art into an embalming exercise.

4

If I do have something to say about Pasolini’s life and work, it’s mostly to get Pasolini-as-figure out of the way, pay whatever homage is due that erotic relation to proper names that typifies contemporary discourse and muddies ‘the thing itself’. (Proper names have taken the place of ‘far out’ for at least two decades.) I have mixed feelings about Pasolini’s overall production and the obstinate anhedonia of his relation to the contemporary world. If there is much to admire about him, there is a good deal less to genuinely like, at least in the unqualified way that I like a film-maker like Buñuel, whose sense of life is far more generative, engaging and empathetic. By the same token, I love Salò (and hate it), which seems, in its vehemence and negativity, its utterly black humour, a repudiation of everything cloying and pretentious in Pasolini’s other work.

5

Salò is one of those rare works of art that really achieves shock value. Aesthetic shock does have a salutary value, and it’s always amusing to read the outpourings of some cultural wastebasket decrying an artist who deploys shock ‘for the sake of shock’, as if to qualify as a work of art, a work of art has to be something other than a work of art – a tutorial in cherished homilies, an affirmation of quotidian values, and so on. I don’t think art has anything to do with morality and it shouldn’t: I should be able to kill everybody I don’t like in a novel and get away with it, rape a twelve-year-old and piss on my father’s grave. It’s not my job to tell anybody that these things are ‘wrong’. It’s my job to show that these things happen, period.

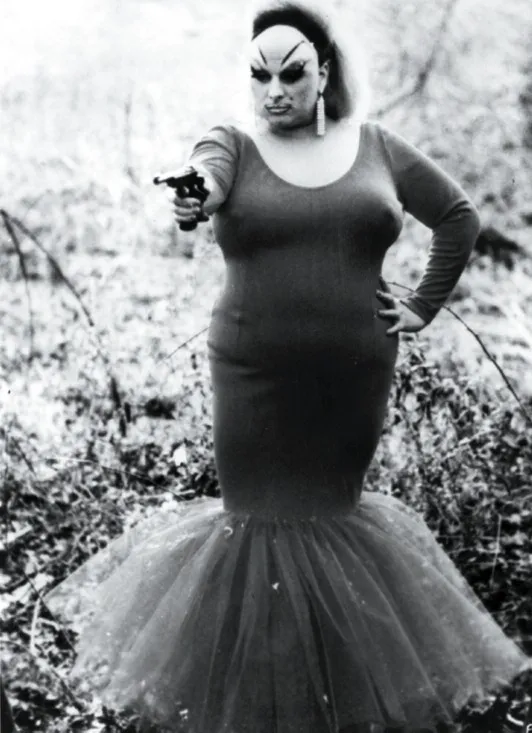

Certain works yank the rug from under the meticulously planted furniture of middle-class morality and the aesthetic torpor that decorates it. John Waters’s Pink Flamingos, Jean Rouch’s Les Maîtres fous, Georges Franju’s Le Sang des Betês, Andy Warhol’s Blue Movie, anything by Hershel Gordon Lewis, scattered moments in the films of Kenneth Anger, Jack Smith, Jonas Mekas – well, you can make your own list of things that lifted the top of your head off. I’m not sure that anyone is obliged to like works of art that fall into this category, or that liking them is ever entirely the point, though critics, quite often, mistake the celebration of the ghastly as an ‘indictment of contemporary malaise’, etc. – in other words, they can only like something if it can be bent to reflect their own moral certainties.

Pink Flamingos: shock has its own salutary value; Pasolini

One way that Salò differs from the unabashedly perverse epiphanies of the cinema of shock is in its pedantic moralism, which might have ruined it if the shock part didn’t so thoroughly overwhelm the moralism. There is something absurdly winning about Pasolini’s explanation of the shit-eating in Salò as a commentary on processed foods, and the fact that Pasolini was being sincere when he said it. And if you think about it, his interpretation is essentially reasonable, though it’s hardly the first thing a viewer thinks when watching a roomful of people gobbling their own turds.

Conspicuous consumption

6

The atmosphere of scandal that misted Salò when it appeared was an aerosol of semen, excrement and blood. Salò was awash in come and shit. The blood was Pasolini’s. His murder, a gruesome affair involving a nail-studded fence picket and his own sports car, struck many as all of a piece with the sadomasochism of his last movie, and with a well-advertised lifetime of patronising rough trade. One French reviewer urged that Salò be shown as a defence exhibit at the murderer Pelosi’s trial,1 on the assumption that anybody capable of directing such a film was practically begging to be murdered.

This coincidental intersection of art and life, or art and death, became an inevitable ending, especially in a right-wing Italian press ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Salò

- Notes

- Credits

- Bibliography

- eCopyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Salo by Gary Indiana in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.