- 104 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

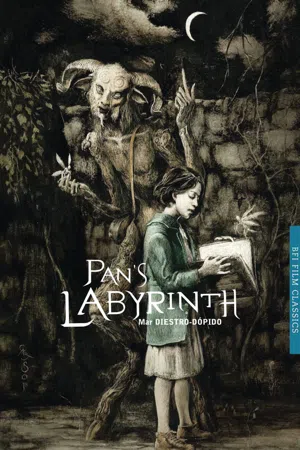

Pan's Labyrinth

About this book

Guillermo del Toro's cult masterpiece, Pan's Labyrinth (2006), won a total of 76 awards and is one of the most commercially successful Spanish-language films ever made. Blending the world of monstrous fairytales with the actual horrors of post-Civil War Spain, the film's commingling of real and fantasy worlds speaks profoundly to our times.

Immersing herself in the nightmarish world that del Toro has so minutely orchestrated, Mar Diestro-Dópido explores the cultural and historical contexts surrounding the film. Examining del Toro's ground-breaking use of mythology, and how the film addresses ideas of memory and forgetting, she highlights the techniques, themes and cultural references that combine in Pan's Labyrinth to spawn an uncontainable plurality of meanings, which only multiply on contact with the viewer.

This special edition features an exclusive interview with del Toro and original cover artwork by Santiago Caruso.

Immersing herself in the nightmarish world that del Toro has so minutely orchestrated, Mar Diestro-Dópido explores the cultural and historical contexts surrounding the film. Examining del Toro's ground-breaking use of mythology, and how the film addresses ideas of memory and forgetting, she highlights the techniques, themes and cultural references that combine in Pan's Labyrinth to spawn an uncontainable plurality of meanings, which only multiply on contact with the viewer.

This special edition features an exclusive interview with del Toro and original cover artwork by Santiago Caruso.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Pan's Labyrinth by Mar Diestro-Dópido in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film History & Criticism. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 The Horror(s) of War

The Spanish War(s)

Although the triangle formed by Ofelia, Vidal and the maquis constitutes the indisputable base for conflict in Pan, war itself is the unnamed puppeteer in the film, as it conditions every character’s actions and reactions. Even though the Civil War had in theory ended in 1939, the embers were still not completely extinguished five years into the so-called Peace Years, the period in which Pan is set. Then as now, the war haunts the collective memory of Spain like the ghost that Dr Casares defines in Devil,

What is a ghost? A tragedy condemned to repeat itself time and again? An instant of pain, perhaps. Something dead which still seems to be alive. An emotion suspended in time. Like a blurred photograph. Like an insect trapped in amber.31

Described by historian Stephen Schwartz as ‘the twentieth century’s most poignant and passionate historical conflict’,32 the Spanish Civil War took place between 1936 and 1939. Its trigger was the uprising of a section of the army against the democratically elected Second Spanish Republic (1931–9). It concluded with the victory of the rebels led by General Francisco Franco, who established a thirty-six-year-long dictatorship, with the help initially of North African troops, and later of Hitler and Mussolini.33 Although figures are still disputed, the consequences of this extremely bloody fratricidal war include: 450,000 exiled, mainly to Argentina, Mexico, France and the USSR; 35,000 children evacuated; 500,000 killed during the war, to which number should be added those murdered during the ensuing dictatorship, and who died owing to hunger and illness, etc.34

It is worth noting that the debates that had been escalating in the media about disinterring victims of the war, particularly since the election of the Socialist Party (PSOE) in 2004, culminated one year after the filming of Pan in the passing of the Law of Historical Memory by the Spanish Prime Minister, José Luis Rodríguez Zapatero. This law overturned the previous Pact of Forgetting, otherwise known as the Pact of Silence – itself passed two years after Franco’s death in order to safeguard the peaceful transition to democracy, by preventing the past being used as a political weapon. As novelist Javier Cercas notes, that did not mean that people had forgotten; on the contrary, after Franco’s death there was an explosion of cultural artefacts offering revisionist takes on the conflict (novels, films, TV programmes), and it was a subject of much discussion. Yet many preferred silence, until this was finally banished by the Law of Historical Memory, legalising the exhumation of bodies from unmarked mass graves of those killed in the struggle against the ‘Victorious’ during and after the conflict, resurrecting their memory in extensive media coverage and public debate. From around 2000 onwards, Spanish horror films in particular refer heavily to this unearthing of the undead past which haunts the collective imaginary, including Los Otros/The Others (2001), The Orphanage, Blancanieves/Snowwhite (2012), GdT’s own Devil’s Backbone and even Pedro Almodóvar’s Volver (2006). In Pan the memory of those erased by Francoist retellings of history is reawakened in the shape of the insurgents – the ‘creatures’ hidden in the forest – who carry on fighting against the newly imposed dictatorship.

The region recreated in Pan is supposed to be in the north of Spain, more precisely Galicia, as evidenced by the accents of Mercedes and the women working in the kitchen.35 Galicia was not only Franco’s birthplace but is also one of the earliest inhabited regions of Spain. The stone carvings scattered about its landscape date back to the Paleolithic era, and in the Spanish imaginary, superstition and magic still very much abound in its thick forests. As well as being near the border with France (Galicia actually borders with Portugal, but the latter was also in the throes of a dictatorship at this point), this dense, foggy and mountainous area was strategically important for the maquis, since it is where the first Spanish guerrilla movement with a military staff committee was established in 1942,36 leading to the creation of the Federation of Guerrillas from Galicia-León, which served as a model to other groups throughout the country. The regime’s response was to send Civil Guards (i.e. Franco’s rural police force) and even army personnel (such as Captain Vidal) to combat these guerrillas. Nevertheless, the maquis in the forests resisted the regime for some time after the Civil War and, although none remained by 1952, myths and legends about them persisted for decades.37 GdT’s film can thus be situated within a larger Spanish tradition that regards the forests of the north of Spain as spaces inhabited by ‘hidden’ creatures, in cult films such as José Luis Cuerda’s El Bosque Animado/The Living Forest (1987, also set just after the war) or, closer to Pan in its focus on memory and identity, Julio Médem’s Vacas/Cows (1992), in which the ancient history of the Basque forests is the natural link between two key wars in Spanish history: the Carlist War and the Civil War, witnessed through the eyes of a cow. The remnants of the insurgents’ ‘underworld kingdom’ are present in the still visible trenches scattered around the Spanish landscape, their ghosts reawakened as their bodies are exhumed.

The maquis in the forest

Vacas/Cows

Despite being set in Galicia, Pan was actually filmed in the Natural Park of Aguas Vertientes y de la Garganta, El Espinar, Segovia, which is part of the Sierra del Guadarrama in central Spain (covering an area of Castilla and Madrid), a mountain range that extends for eighty kilometres. The history of this area of Spain can be traced back to the Roman Empire, and its position as natural barrier means many armed conflicts in the peninsula have taken place here, from the battles between Christians and Muslims, to the War of Independence with France, 1808–14, depicted by Goya in his famous painting ‘Los fusilamientos del 3 de mayo’/‘The Shootings of May Third’ (1808). More relevant for our purposes is the fact that, despite being the site of massive resistance to Francoist troops during the war,38 it is also home to the biggest extant monument to fascist Spain, El Valle de los Caídos, or Valley of the Fallen, built to commemorate those who perished on the Nationalist side as well as to house Franco’s tomb. Many key films have been shot in this area, including two by Carlos Saura: his debut feature, La caza/The Hunt (1966), a powerful allegory about the Civil War, and Ana y los lobos/Ana and the Wolves (1973), a metaphorical exploration of Spain’s post-war isolation and ideological and sexual repression. Pan’s depiction of fascist Spain falls firmly within this tradition of films dealing metaphorically with the war and its aftermath, and, most importantly, feeds into important current historical debates around collective memory and the manipulation of the past.

Both Pan and Devil are testament to the powerful grip the Civil War has exerted not just on a Spanish but on an international cinema audience. Schwartz explains why.

Goya’s ‘Los fusilamientos del 3 de mayo’/‘The Shootings of May Third’ (1808)

La Caza/The Hunt; promotional poster for Ana y los lobos/Ana and the Wolves

The Spanish civil war is often described as ‘the last idealists’ war’, when it would be better called the last authentic social revolution. Because of the deep emotion, symbolism, myths, parables, and allegories the war evoked and created, it became the first ‘proto-cinematic war’, in which dramatic images generated in newspapers, newsreels, and the work of individual photographers and poster artists were clearly destined to become the raw material for a distinctive cinematic genre.39

The multiplicity of films and TV on the subject in Spain – comedies, documentaries, sitcoms, animation – attempt on the whole to counter the one-sided history, permeated by myth, which Franco’s intelligentsia constructed of Spain. Internationally, the range of titles about the conflict is also vast: Hollywood classics such as For Whom the Bell Tolls (1943) and The Fallen Sparrow (1943); films dealing with the war’s aftermath and exile such as Behold a Pale Horse (1964) and La Guerre est finie/The War Is Over (1966, written by Spanish ex-Communist Jorge Semprun); films focusing on collaboration between Francoism and Nazism such as The Angel Wore Red (1960); and British director Ken Loach’s own idealised version of the conflict Land and Freedom (1995).

Schwartz sees these foreign perspectives on the war, their tendency to approach it through Anglo-American historiography, as problematic:

[there was] a gap between the war as experienced or observed by foreigners, who saw in it mainly a contest between external fascist and democratic powers, and as lived by the Spanish peoples themselves, who viewed it as a profound social transformation. This became a repetitive pattern of twentieth century intellectual dissonance.40

It’s a flaw he finds particularly problematic in Land and Freedom, which he considers to be ‘no less a fantasy, outside Spanish reality, than Pan’s Labyrinth – but the latter at least embodies a Hispanic consciousness absent from Loach’s work...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- 1. The Horror(s) of War

- 2. Vidal and Amnesia

- 3. Ofelia and Memory

- 4. The End …

- Coda: Phone Interview with Guillermo del Toro

- Notes

- Credits

- Bibliography

- eCopyright