![]()

1 Actors and Auteurs

A film is clearly a collaboration between a large number of people – the lengthy end credits of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind going some way to demonstrate this. While film criticism has sometimes focused on the director when auteur-inflected – situating the film within Michel Gondry’s career – and a more literary approach would be to focus on the scriptwriter as the source of meaning – say, recurrent themes and style in the work of Charlie Kaufman – films are often sold on the strength of their actors. Although some films have posters saying ‘From the producer of –’ or ‘From the director of –’, and Kaufman was a sellable commodity on the back of Being John Malkovich (1999) and Adaptation. (2002), a star actor is a more common way of preselling a film. In casting Jim Carrey and Kate Winslet, Eternal Sunshine benefited from the publicity that the two stars generated. Each actor brings the baggage of his or her previous roles to a new project, a certain expectation on the part of the audience. Oddly, Carrey is largely cast against type here, which risked alienating the audience by failing to give them what they expect, and Winslet felt as if she was, but that underplays the agency that her earlier characters grasped in settings where opportunities for women were more limited. Before examining the careers of Kaufman and Gondry, I want to look at the baggage that the earlier work of Carrey and Winslet brought to their roles.

Jim Carrey

Canadian Jim Carrey stands in a tradition of film character comedian actors whose performances both sell and transcend specific films. As Philip Drake argues: ‘More than perhaps any other genre, pleasure in comedian comedy relies on our pleasure in watching the star performance.’8Mixing verbal comedy with physical presence, they frequently acknowledge the audience, by breaking the fourth wall or with an extradiegetic look; in The Mask (1994), the masked Stanley Ipkiss (Carrey) looks at and speaks to the audience, declaring ‘it’s show time’ and very clearly performing and acknowledging that he is performing. According to Steve Seidman, the character comedian would already be familiar to that audience through work in other media – initially theatre, music hall, vaudeville and radio, but more recently television or stand-up – and thus on some level be a known quantity.9 The comedian actor is placed within a film in a number of semantic frames simultaneously:

1as a fictional character within a given narrative and diegesis;

2as celebrity and star familiar from news stories and interviews;

3as recurring actor who has played other roles in other films (and in other narratives); and

4as a physical body whose mannerisms we recognise.10

In Eternal Sunshine, Carrey ‘is’ Barish – or indeed a number of Barishes according to their position in the story, bitter, spotless or sadder and wiser.11 Carrey would be familiar to audiences from coverage of red carpets at premieres and award shows and his earlier star vehicles such as the Ace Ventura films (see below).

Dave Kehr suggests that Carrey is ‘the first major American comic to grow up with television in his bloodstream’,12 noting the significance of the medium in many of his movies, from the alien being educated by TV in Earth Girls Are Easy (1989) to TV as womb in The Truman Show (1998). After struggling in stand-up comedy and gaining a few small roles in films such as The Dead Pool (1988), Carrey became part of the ensemble cast of Keenen Ivory Wayans and Damon Wayans’s sketch show In Living Color (1990–4). His debut leading feature role, Ace Ventura: Pet Detective (1994), establishes the Carrey persona as goofy outsider who never takes those in authority seriously. He pulls and twists his face, throws his body around (and ventriloquises his bottom) as well as speaking in exaggerated and nonsensical tones. He is always performing to an audience, real or imagined. When Lt Lois Einhorn (Sean Young) – eventually exposed as the villain – says, ‘Spare me your routine, Ventura’, it can become easy to empathise. In The Mask, special effects transform Carrey into a three-dimensional cartoon character as he dons a magical mask and causes chaos across a city. The sense that the masked version of the character is giving free vent to his desires is undercut by his hyperactivity when not masked. Although in Batman Forever (1995) Carrey had licence to overperform as The Riddler, he allowed ‘himself to be upstaged by Tommy Lee Jones’s more flamboyant performance’13 as Two-Face.

Liar Liar (1997): Carrey’s smile is part of his performance style

Carrey had to tone down his normal style for Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind

The Truman Show (1998) was a more serious role

As with the career of fellow character comedian Robin Williams, Carrey also took on more serious roles. In The Truman Show, there is a childlike element to his portrayal of Truman Burbank, unwitting reality show star at the centre of a stage set. By keeping his mannerisms in check, he enables the audience to empathise and it is this aspect of his persona that helps us care about Joel’s plight in Eternal Sunshine. In the Andy Kaufman biopic, Man on the Moon (1999), he transforms himself into the comedian, his excessive performance anchored within the earlier character comedian’s personae. Carrey must reel himself in for the more reflective scenes, especially in the later sequences. The Majestic (2001) is an uneasy homage to Capraesque patriotism set against the Hollywood blacklists; Peter Appleton (Carrey) is accused of communist sympathies and crashes his car on his way out of town. Suffering from amnesia, he ends up in a small town, mistaken for a missing war hero. Carrey’s performance makes his character likeable and has all his desires gratified even after his inadvertent deception is revealed. In these films, there is a tension between his star persona and the rather more buttoned-down character that he is required to represent. It is very much this depressive counter to the mania that Michel Gondry was to exploit in Eternal Sunshine. His relatively subdued performance seems all the more so in comparison to, say, Liar Liar (1997) where for much of the film Carrey stays at fever pitch. The combination of gurning, his Jerry Lewis-like movements and his smile is ‘a key signifier in Carrey’s idiolect’.14

A part such as Joel might be in tension with his pre-existing star persona. As Henry Jenkins points out:

Most film performances maintain some degree of distance between the star’s image and the film’s character, though certain types of film (comedy, musical) focus audience attention on that gap while others (social problem films, melodramas) efface it as much as possible.15

There is often a shift of gear between ‘acting’ and ‘performance’, the realism of the plot and the comic, knowing exaggeration of the carnivalesque star turn. In some cases, there is an attempt to naturalise and frame the performance – a split personality, possession, the gigs of Andy Kaufman within Man on the Moon (and the films within films of Gondry’s Be Kind Rewind offer a similar alibi for Jack Black), but Carrey’s Fletcher Reede in Liar Liar seems equally unhinged in the courtroom and outside it, under a spell and not. Pleasure derives from his comic performance.

Kate Winslet

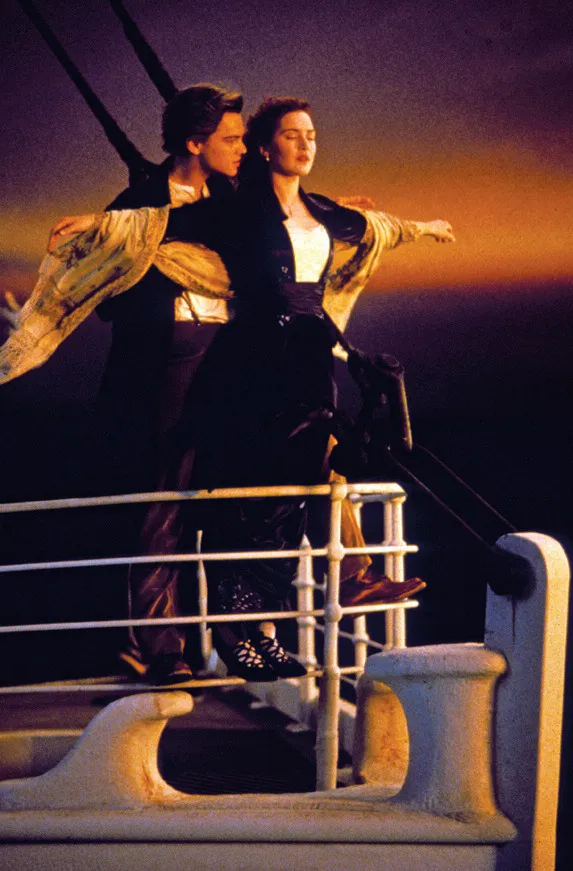

British-born Kate Winslet had won a Best Supporting Actress BAFTA for her role as Marianne Dashwood in Sense and Sensibility (1995), but it was playing upper-class Rose DeWitt Bukater who falls in love with working-class Jack Dawson (Leonardo DiCaprio) in the blockbuster Titanic (1997) that made her an international star. Rose’s sexual awakening opens up the possibility of a life beyond marriage – although as Alexandra Keller notes, ‘Rose has led an adventurous but expensive life’.16 Keller argues that Rose is one in a line of ostensibly feminist protagonists in Cameron’s films: ‘Winslet’s high-spirited, loogey-hocking wannabe heiress (or, more to the point, don’t-wannabe heiress) is as independent, smart, idiosyncratically beautiful, sexy, powerful, (fill in another complimentary adjective here […]) as Cameron’s previous leading women.’17 For Keller, Rose ends up reinforcing the values of patriarchy and the ruling class. Nevertheless, this ensured Winslet was a box-office draw, allowing her more freedom in her choice of roles as well as attracting audiences to Eternal Sunshine.

Poster for Heavenly Creatures (1994)

Titanic (1997) made Winslet a household name

In Iris (2001), Winslet delivered a more liberated performance, but within an historical context

Before Titanic, and after, as she returned to lower-budget films, she has tended to be in historical dramas: as Juliet Hulme in Heavenly Creatures (1994), based on the real-life Hulme–Parker murder of Parker’s (Melanie Lynskey) mother (Sarah Peirse); as a mother finding herself in 1970s Marrakech in Hideous Kinky (1998); in the aforementioned Austen adaptation Sense and Sensibility; as Hester Wallace in the World War II drama Enigma (2001) and as the you...