eBook - ePub

Vampyr

About this book

Described by its maker as a 'poem of horror', Vampyr (1932) is one of the founding works of psychological horror cinema, adapted from a collection of gothic stories by Sheridan Le Fanu and directed by the revered Danish director Carl Theodor Dreyer. Despite the fact that there is no definitive print and many English versions are marred by poor quality subtitles, the film remains a vivid, extraordinary artwork in which the inner human state is made hauntingly visible.

In a reading as passionate as it is analytic, David Rudkin reveals how this film systematically binds the spectator – spatially and morally – into its mysterious world of the undead.

This second edition features a new foreword, discussion of the Martin Koerber and Cineteca di Bologna restoration of the film in 2008, and original cover artwork by Midge Naylor.

In a reading as passionate as it is analytic, David Rudkin reveals how this film systematically binds the spectator – spatially and morally – into its mysterious world of the undead.

This second edition features a new foreword, discussion of the Martin Koerber and Cineteca di Bologna restoration of the film in 2008, and original cover artwork by Midge Naylor.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Carl Theodor Dreyer1 (1889–1968)

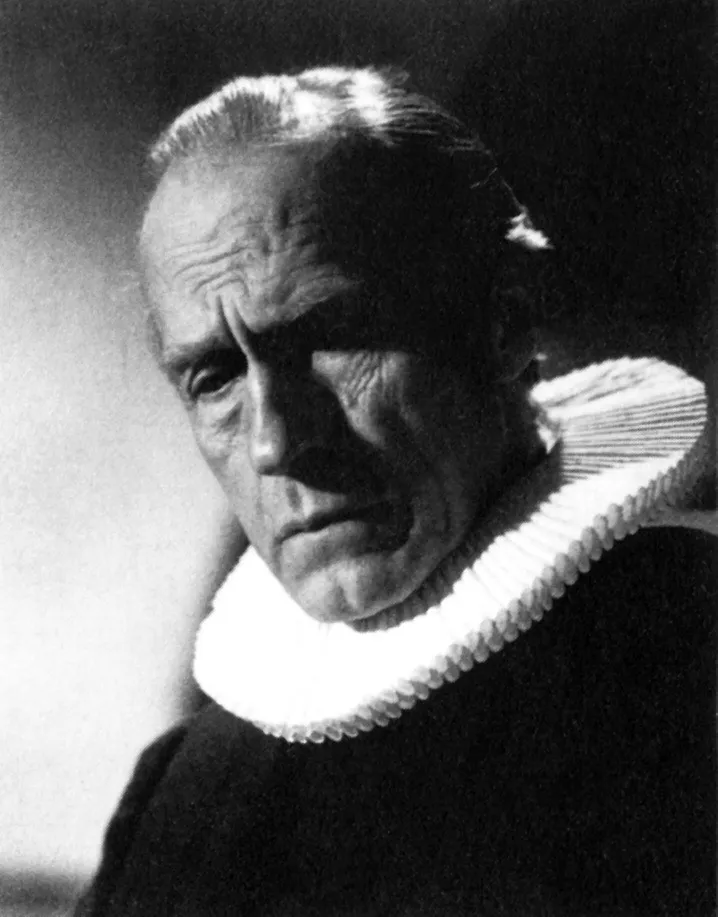

Dreyer is a legendary figure in film history. The director of the venerated Passion of Joan of Arc (1927) haunts the shadowy background of world cinema, a mythical presence who seems now all but faded. Yet a photograph of Dreyer, taken on something so earthbound as a set for Joan, shows a human being substantial and pragmatic enough. In cap and belted jacket, he is standing with his crew in a dolly-trench: those iconic low-angle tracking-shots did not come from nowhere.

Dreyer

And the director had not come from nowhere. We can locate Dreyer more vividly when we reflect that he was twelve years old when Ibsen died; that (after an initial career as a young journalist) he began his own first essays in professional screenwriting in the year after Strindberg’s death; that it was after the experience of seeing Griffith’s latest, Intolerance (1916), that he decided to become a director. As political background, raged the blood letting of World War I, then that war’s revolutionary aftermath in Germany and Russia. In his native cultural inheritance, meanwhile, we see two powerful forces at work: a newly emerging, characteristically ‘Scandinavian’ cinema, pioneered by Swedish directors Mauritz Stiller and Victor Sjöström and his own countryman Benjamin Christensen; and the theatre of ‘Ibsen and after’.

In Dreyer’s own beginnings as a director, it is Griffith whose example we see at first most guiding him; but it is in the more poetic, ‘Nordic’ naturalism of Stiller and Sjöström that he will soon find his truer self. Christensen’s was a darker art, of an expressionist before his time. Acknowledged as the earliest ‘real’ director in film history, he is Dreyer’s senior by only ten years. In Christensen’s Häxan (The Witch, 1918–212), we find more than once the archetype of an image that Dreyer will later intensify. We note also how Christensen locates the cinema’s true landscape of ecstasy and suffering in the human face. It is on the face – of ecstatic, torturer, victim – that the moral meaning of the act is visible. This would become a central principle of Dreyer’s art, and will appear at its extreme in the remorseless procession of high-intensity close-shots that is Joan. Dreyer himself spoke of the face as a ‘land that one never tires of exploring’.

Christensen, 1921; Dreyer, 1943

The Passion of Joan of Arc (1927); Day of Wrath (1943)

In citing Ibsen’s also as an informing legacy, I think particularly of the later, so-called ‘prose’ plays, from Pillars of the Community (1878) onward. Ibsen’s theatre confronts the rigid order of Scandinavian domestic and social life – in Denmark, a quietist, sometimes quaint punctiliousness – with troubling intimations of the repressed; a dramaturgy, its explosiveness enhanced by its constraint. This would furnish an abiding paradigm in Dreyer’s aesthetic, still operative in his valedictory Gertrud of 1964.

But all thought of ‘influence’ and ‘inheritance’ falls away as we confront the unique presence of Dreyer’s art onscreen. For there is another force imbuing this art, a force more visceral – a Lutheran sense of each human creature as unalterably alone, each working out (or losing) an individual salvation, in an existential solitude that only love can mitigate. This severe theology is enacted amid a Nature whose humblest and most earthly textures are yet suffused with ‘the spiritual light of common things’.3 One can feel just such a presence in the stillness of a Scandinavian country church, amid its squared straight timber and filtered white light. It is this, perhaps, that characterises for most of us what we know of Dreyer’s cinema: the texture of a wooden door or beam, of a white stone wall, of a human face, the soul illuming its physical landscape from within, in iconic extremity as in Joan, or squarely framed and dense as a Rembrandt. We may remember images, too, of waving grasses, of foliage touching with dancing shadow moments of human love and death. No other artist awakens in us quite so searing a sense of the rapture and the sorrow of our human transience amid eternity. Dreyer’s cinema makes ours visionary eyes.

I revere Carl Dreyer more deeply than any other artist of my time. I feel a sense of presumption in writing about him, let alone something so generalising as an ‘overview’. But his work is in great part unknown, and some background must be given.

Coming to Dreyer’s films in their chronological sequence, as we might at a retrospective season, seeing the early work and knowing nothing of what is to follow, we will feel some dismay. Dreyer’s debut, Præsidenten (The Chief Justice, 1918), will seem in the worst sense ‘of its time’: melodramatic, often openly imitative of Griffith. Its storyline could be the premise of an 1880s Ibsen play: a high-ranking Justice condemns his unacknowledged illegitimate daughter for killing a natural child of her own. Perhaps Dreyer was exorcising something here: it had been painful for him to discover his own illegitimacy, and he seems to have developed a belief that his ‘real’ father, who had repudiated him and his mother (she killed herself two years later, trying to abort another child), was just such a ‘pillar of the community’. Griffith’s hand is visible in Dreyer’s second film too, Blade af Satans bog (Pages from Satan’s Book, 1919), drawn mainly from Marie Corelli’s novel The Sorrows of Satan and deploying four distinct narratives, three historical and one contemporary, as Griffith had done in Intolerance. Dreyer does not interweave his narratives in the contrapuntal manner of Intolerance – this he may well have felt an imitation too far – but in juxtaposing the stories separately, he sets himself a problem, in that the final story alone must carry the film’s climax. Of these early films, Die Gezeichneten (The Branded, 1921) is perhaps the most discouraging. A German production featuring a Teutonic, Nordic and Slavic mix of actors variously exiled by war and the Bolshevik Revolution, it is a complex story of prejudice and hatred in the volatile Russia of 1905. As its English title Love One Another suggests, its heart is in the right place; but it leaves a heavy and confused impression. Der var engang (Once Upon a Time ..., 1922) promises something different, a fairy tale of enchantment (not something we might associate with Dreyer). But promise is now all we have, for the film is mainly lost and only tantalising fragments survive.4 This was Dreyer’s second collaboration with lighting cameraman George Schnéevoigt, and what we have of it looks remarkable. But Dreyer himself would later say of it that ‘atmosphere’ alone was not enough.5

Day of Wrath (1943); Ordet (1955)

Seen through the lens of Dreyer’s later work, these early films are rich in pre-echoes and foreshadowings. But, watching in innocence of what is to come, we might well part company with Dreyer now – but for one film that I have not mentioned. His third film, Prästänkan (The Parson’s6 Widow, 1920), is in a strict sense his masterpiece, the work in which he emerges from apprenticeship. Here Dreyer suddenly finds himself, and on an authentic footing in his own Nordic tradition, the poetic naturalism of Stiller and Sjöström, but of a brand more four-square and Puritan all his own. The Parson’s Widow has its origins in an incident recorded from a seventeenth-century Swedish country parish. Seeking appointment to the living, a newly ordained young pastor inherits the previous incumbent’s ancient widow too. The redoubtable Dame Margarete has already buried three pastor-husbands, and now exercises her traditional right to claim young Söfren as her fourth, and so hold onto her home and her livelihood. Söfren prevails on her to employ his sister as a servant. But the ‘sister’ is in fact his mistress ... Filmed in Norway, at the Sandvig museum village near Lillehammer, The Parson’s Widow lovingly recreates a seventeenth-century rustic Lutheran milieu, almost three-dimensional in its onscreen presence of timber of wall and door, of bed and beam. There is a vein of earthy comedy too – again, not something readily associated with Dreyer. Yet this world of texture and substance is imbued as with a hallowing light – this marks Dreyer’s first collaboration with Schnéevoigt – and, with a masterly elegance, broad comedy yields to the elegiac. Dame Margarete acknowledges that the time has come for her to yield place to the young. In a heart-stopping sequence, she bids a dignified farewell to the landmarks and creatures of her parsonage and its world, then composes herself for her approaching end.7 Here, we glimpse what later we shall know for quintessential Dreyer: amid the benedictory textures of Nature, intimations of the dual presence of Love and Death, which sear the soul with a sense of the sorrow and the beauty of the earth; and ever that ‘spiritual light of common things’. The Parson’s Widow is our first vision of the Dreyer to come.

Foreshadowing: Præsidenten (1918); Ordet (1955)

Three years later, he will again be master, and master thereafter. Yet in Mikaël (1924), we find Dreyer in the very last landscape we should have expected. Again a German production (for UFA), Mikaël inhabits a ‘decadent’ fin-de-siècle world. Dreyer is yoked here with such German Expressionist heavies as Thea von Harbou (co-screenwriter), Erich Pommer (producer) and lighting cameraman Karl Freund, and will himself direct his own revered senior, Christensen, as an ageing painter in love with, and destroyed by, the beautiful and cruel young Mikaël.8 UFA notwithstanding, the express...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- 1 Carl Theodor Dreyer (1889–1968)

- 2 Locating Vampyr in Dreyer’s Cinema and in its Sources

- 3 The ‘Problem’ of Vampyr

- 4 Vampyr: Towards a Reading

- 5 The Journey to Our Grave

- Notes

- Credits

- eCopyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Vampyr by David Rudkin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.