![]()

CHAPTER 1

Tales of the China Clipper

In the year 1768, on the eve of China’s tragic modern age, there ran through her society a premonitory shiver: a vision of sorcerers roaming the land, stealing souls.1 By enchanting either the written name of the victim or a piece of his hair or clothing, the sorcerer would cause him to sicken and die. He then would use the stolen soul-force for his own purposes. What are we to make of this hysteria that affected the society of twelve great provinces and was felt in peasant huts and imperial palaces?2 Were the conditions of the age (seemingly so prosperous) sending warnings about the future that could be sensed only in the guise of black magic? Men and women of the eighteenth century—before the West arrived in force—were already creating the conditions of China’s modern society. In the light of what the Chinese have experienced since, it would not be surprising to find that their eighteenth-century ancestors perceived these conditions as phantom images of fearsome power.

Though we say that we cannot see the future, its conditions lie all around us. They are as if encrypted. We cannot read them because we lack the key (which will be in our hands only when it is too late to use it). But we see their coded fragments and must call them something. Many aspects of our own contemporary culture might be called premonitory shivers: panicky renderings of unreadable messages about the kind of society we are creating. Our dominating passion, after all, is to give life meaning, even if sometimes a hideous one.

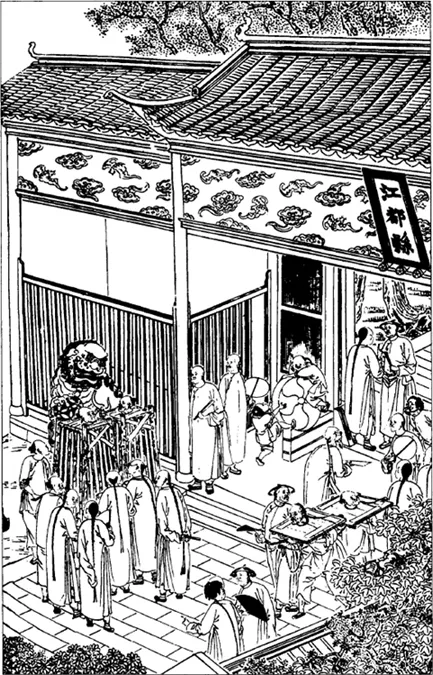

Loading dock at a silk plantation in Hu-chou, Chekiang Province.

A Westerner’s impression from the nineteenth century.

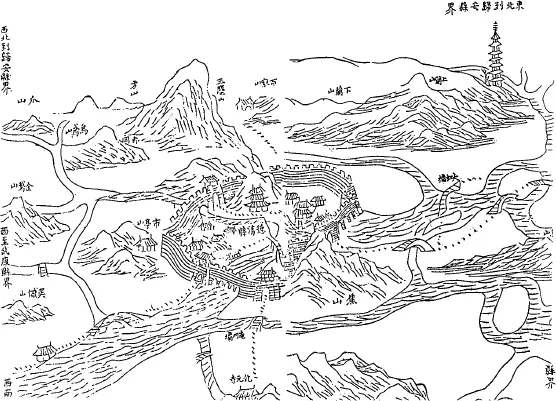

The Masons of Te-ch’ing

The silk district of Chekiang Province, “one vast rich and fertile mulberry garden,” is a virtually flat floodplain, laced with creeks and canals and studded with residual hills, which appear to a visitor “as if they had been thrown out as guards between the vast plain, which extends eastward to the sea, and the mountains of the west.”3 A century before the time of our story, the inhabitants were already so committed to the silk industry that “no place was without mulberry trees, and in the spring and summer not a person was not engaged in sericulture.” Day and night, wrote a seventeenth-century observer, the inhabitants worked to harvest the raw silk, “which they produce to pay their taxes and rent, and on which they rely for clothing and food.” So wholly dependent were they on the silk market that “if ever it is unprofitable, they have to sell their houses and property.”4 In the midst of this thoroughly commercialized district lay the county seat of Te-ch’ing, some twenty miles north of historic Hangchow. The river Nan-t’iao, on its way northward to Lake T’ai, ran right through the walled city. In 1768, the thirty-third year of the reign of Hungli (Ch’ien-lung),5 fourth monarch of the Manchu Ch’ing Dynasty, the water-gate and bridge in the eastern side of the city wall had fallen to ruin and needed rebuilding.6

Magistrate Juan hired the mason Wu Tung-ming from Jen-ho, the neighboring county. Wu and his crew began, on January 22, the heavy work of pounding the great wooden pilings into the riverbed. The water was running high, and the men struggled at their task.7 Nevertheless, pilings were sunk by March 6, and Wu’s men began to install the new gate. By the twenty-sixth, Wu was running low on rice to feed his men and made the ten-mile journey to his home town, the commercial center T’ang-hsi on the Grand Canal, to buy a fresh supply. When he arrived home, he learned that a stranger had been asking for him: a peasant named Shen Shih-liang, who proceeded to seek Wu’s help in a curious and frightful project.

Peasant Shen, aged forty-three, lived in a family compound with two sons of his deceased older half-brother.8 These harsh, violent men tormented him, cheated him of his money, and even beat and abused his mother. Without hope of earthly remedy, he besought the powers of darkness. At the local temple he filed a formal “complaint” with the King of the Underworld by burning a yellow paper petition before the altar.9 In February, Shen heard of a promising new remedy: travelers brought news of the Te-ch’ing water-gate project. They had heard that the masons needed the names of living persons to write on paper slips, which could be nailed onto the tops of the pilings to add spiritual force to the blows of the sledgehammers. This was called “soulstealing” (chiao-hun). Those whose soul-force was thus stolen would fall ill and die. With renewed hope, Shen had written the names of his hated nephews on slips of paper (since he himself was illiterate, he painstakingly copied them from an account book kept by his nephews in connection with a commercial fishing venture). Now producing the rolled-up slips of paper, Shen asked mason Wu: What about it? Do you practice this technique?

Wu would have none of it. He knew that masons, along with carpenters and other builders, were commonly thought to have baleful magical powers (as I shall explain in Chapter 5). He was also, no doubt, aware of the kind of rumors peasant Shen had repeated, and feared that he might be implicated in this hated practice of soulstealing. He quickly summoned the local headman and had Shen brought to Te-ch’ing for questioning. Magistrate Juan settled the matter by having Shen beaten twenty-five strokes and then released. Mason Wu’s misadventures with sorcery, however, were not over: he was soon to be implicated in an outbreak of public hysteria.10

The walled city of Te-ch’ing. Water-gates can be seen at right and lower left of the city.

One early spring evening, a Te-ch’ing man, Chi Chao-mei, had been helping with funeral arrangements at the house of a recently bereaved neighbor. On his way home he had a few drinks, and he was relaxed enough by the time he reached his house that his uncle suspected him of having been out gambling and began to beat him. Smarting and fearful, Chi fled the house and walked the twenty-odd miles to Hangchow, the provincial capital, where he thought to support himself by begging. After midnight on April 3, he found himself before the Temple of Tranquil Benevolence near the shore of Hangchow’s fabled West Lake. A bystander grew suspicious of Chi’s Te-ch’ing accent, and when Chi acknowledged his origins, a crowd surrounded him. One man shouted, “Here you show up in the middle of the night, and either you’re about some thievery, or else it’s because you people in Te-ch’ing are building a bridge and you’ve come here to steal souls!” The crowd quickly turned ugly and set upon the outsider, seizing and pummeling him. Off they dragged him to the house of the local security headman.

The headman tied Chi to a bench and threatened to beat him if he held back the truth. The bruised and terrified Chi now concocted a story that he really was a soulstealer. “Since you’re a soulstealer,” shouted the headman, “you must have paper charms on you. How many souls have you stolen?” Chi said he had indeed had fifty charms, but that he had thrown forty-eight of them into West Lake. He had used the other two to cause the deaths of two children, whose names he proceeded to invent.

The next day Chi was taken to the constabulary, and from there to the yamen (government office) of Ch’ien-t’ang, the metropolitan county of Hangchow Prefecture (located in the same city). There Magistrate Chao asked where Chi had obtained the charms, and who had told him to steal souls. Chi had heard the usual rumors about the bridge project in Te-ch’ing, that the pilings had been hard to sink, and that the masons needed names of living persons whose soul-force could lend power to their hammers. He had also heard that the contracting mason was Wu something or other, and that his given name had the ideograph ming in it: “It was Wu Jui-ming who gave them to me.” Mason Wu Tung-ming must by now have been thoroughly dismayed by the hazards of his calling, for he was forthwith haled into the Ch’ien-t’ang County yamen. Luckily, Chi’s perjured story was quickly exposed when he failed to pick Wu from a lineup. Put to the torture, Chi now admitted that his whole story had been concocted out of fear.

Constable leading a prisoner, who is carrying his own sleeping mat and a fan.

The sorcery scare in Chekiang had by now sparked several unpleasant and bizarre incidents. In addition to the affairs of Shen Shih-liang and Chi Chao-mei, there had been the matter of Wu’s coworker, mason Kuo, who, on March 25, had been approached by a thirty-five-year-old herbalist, Mo Fang-chou, who sought to entrap him into placing a paper packet on a bridge piling so Mo could ingratiate himself with the authorities by turning in a soulstealer. The furious mason had seized Mo and dragged him to the county yamen, where the would-be informer was beaten and exposed in a cangue (a heavy wooden stock placed around the prisoner’s neck) for his trouble.

These irksome cases moved the provincial authorities to hold an inquiry in which accusers and accused alike could be questioned, thus to make an end of it. Governor Hsiung Hsueh-p’eng ordered the local prefect to convene a court with the magistrates of Ch’ien-t’ang and Te-ch’ing counties. Chi again failed to identify Wu in a lineup. The authorities searched Wu’s home secretly and found no sorcerer’s paraphernalia. Magistrate Juan had already made discreet inquiries among the bridge-workers and found no evidence that persons’ names had been intoned while the pilings were being driven. Sorcery indeed! Herbalist Mo, peasant Shen, and even the unfortunate Chi Chao-mei were exposed in the cangue at the Hangchow city gates as a warning to the superstitious multitude. After all, nobody had been shown to have sickened or died on account of soulstealing; on the contrary, public credulity had damaged civic order. Such was the agnostic summary later offered to the Throne by Yungde, the succeeding Chekiang governor.11 But fear of sorcery was not so easily exorcised from the public mind.

The Hsiao-shan Affair

On the evening of April 8, 1768, four men, marked as Buddhist monks by their dark robes and shaved heads, met at a rural teahouse in Hsiao-shan County, Chekiang, just across the river from Hangchow. All were based in Hangchow temples and were wandering the nearby villages to beg alms. Sketches of these men may be drawn from their own later testimony.12

Scene at the entrance of a county yamen in the lower Yangtze region. The convicts in cages are being left to die of starvation.

At lower right are two convicts wearing the cangue.

Chü-ch’eng (this was his dharma-name, assumed when he was tonsured as a monk), aged forty-eight, lay surname Hung, was a native of Hsiao-shan County. When he was forty-one, after his parents and wife had all died, he entered a temple in Hangchow called Ch’ung-shan-miao, where he assumed the tonsure.13 There he shared a teacher (master, shih-fu) with the younger monk Cheng-i, and the two addressed each other, in the conventional clerical “family” way, as elder and younger brothers. Chü-ch’eng had not, however, reached the next stage of monastic life, that of ordination. Because his temple had no means of supporting him, he went begging in his native county, where we now find him.

Cheng-i, twenty-two, a native of Jen-ho in Hangchow Prefecture, lay surname Wang, was Chü-ch’eng’s “younger brother.” Because he was a sickly child, his mother had him tonsured at the age of nineteen at the God-of-War Temple outside the city gate. He later studied alongside Chü-ch’eng at Hangchow, but like him did not receive ordination. He joined his “elder brother” to go begging across the river in Hsiao-shan.

Ching-hsin, aged sixty-two, was from the Grand Canal city of Wuhsi in Kiangsu Province; his lay surname was Kung. At the age of fifty, after his parents, his wife, and his children had all died, he journeyed to Hangchow to take the tonsure at a small Buddhist retreat, where he then resided. Later he was ordained at the monastery called Chao-ch’ing-ssu. In the course of his travels to study at various monasteries, he met the monk called Ch’ao-fan, whom he later invited to join him as his junior acolyte.

Ch’ao-fan, forty-three, from poor and mountainous T’ai-p’ing County in Anhwei, lay surname Huang, was Ching-hsin’s acolyte. He had been tonsured at eighteen at a local temple. Later he received ordination at the Tzu-kuang-ssu monastery, whose location is unknown but was probably in Hangchow. He went to live with Ching-hsin in 1756.

The great cultural and religious center of Hangchow had attracted all four: two had forsaken lay life because family deaths had left them alone at what in eighteenth-century China was considered old age. Two had been tonsured in youth: one because of sickness (an economic liability to his family), and the other for reasons unknown. Two bore the government-mandated identity papers (ordination certificates) and two did not. Now all four were pursuing the most common outside occupation of monks: begging. Apart from the spiritual benefits of begging (a demonstration that they had renounced worldly concerns), their monastic homes lacked the means to support them. We do not know exactly the extent of the catchment basin of Hangchow mendicants, but Hsiao-shan was right across the river from the city, and at the teahouse the four decided to set forth together there the next day. Chü-ch’eng and the elderly Ching-hsin would spend the day begging in the villages, while the juniors would carry everyone’s traveling boxes to the old God-of-War Temple near the west gate of Hsiao-shan City.

A wandering Buddhist monk, in an eighteenth-century Japanese impression gleaned from Chinese merchants at Nagasaki.

The stubble of hair betrays a degree of indiscipline that would not have been tolerated ...