eBook - ePub

Cultural Studies

Volume 6, Issue 3

Ien Ang, John Hartley

This is a test

Share book

- 152 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Cultural Studies

Volume 6, Issue 3

Ien Ang, John Hartley

Book details

Book preview

Table of contents

Citations

About This Book

First published in 1992. Routledge is an imprint of Taylor & Francis, an informa company.

Frequently asked questions

How do I cancel my subscription?

Can/how do I download books?

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

What is the difference between the pricing plans?

Both plans give you full access to the library and all of Perlego’s features. The only differences are the price and subscription period: With the annual plan you’ll save around 30% compared to 12 months on the monthly plan.

What is Perlego?

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Do you support text-to-speech?

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Is Cultural Studies an online PDF/ePUB?

Yes, you can access Cultural Studies by Ien Ang, John Hartley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Arte & Cultura popolare nell'arte. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

• ARTICLES •

VISIONS OF DISORDER: ABORIGINAL PEOPLE AND YOUTH CRIME REPORTING1

STEVE MICKLER

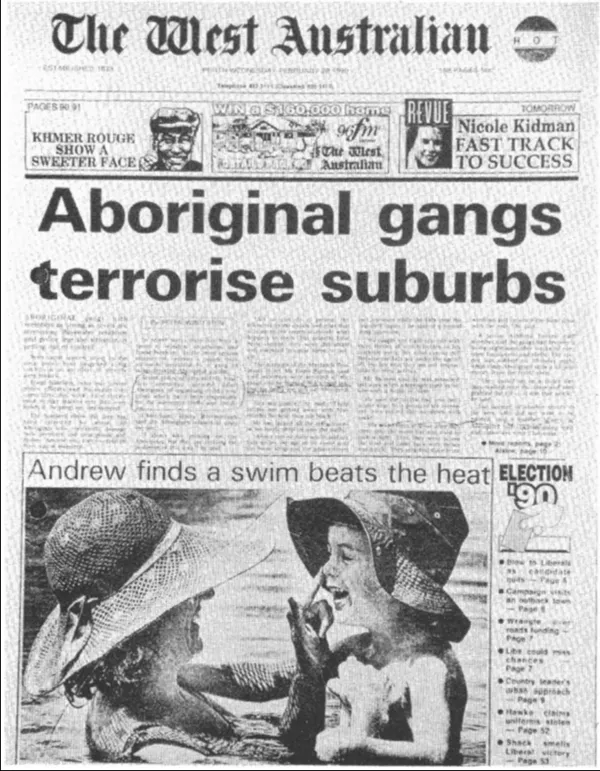

On 28 February 1990 Western Australians awoke to a troubling headline across the front page of the State’s major daily tabloid. On their way to work that morning, commuters passed posters, on the footpaths in front of suburban newsagents and on the corners of city streets, that reproduced, in large type, The West Australian’s main news of the day: ‘Aboriginal gangs terrorise suburbs’ (fig. 1).

As far as Western Australian news media discourses about Aborigines go, the ‘gangs’ story, as it has come to be known, is the ‘had to happen one day’ story. For many years Aborigines in Perth have complained about what they believe to be incessant news media persecution.

These complaints have been voiced strenuously to the Royal Commission Into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, the Human Rights Commission National Inquiry Into Racist Violence, the Australian Press Council, the Australian Broadcasting Tribunal, not to mention the chiefs of newspapers, radio and TV news programs themselves. Anti-Aboriginal media stories have led Aborigines to establish an Aboriginal-Media Liaison Group with sympathetic journalists, to campaign for the removal of a particularly offensive radio commentator,2 and have also given impetus to moves to set up Aboriginal-controlled radio stations in Perth and other towns. So Aboriginal people are by no means passive recipients of news media visions of themselves and broader issues of race relations and representation. Indeed, they have also become active participants in setting and influencing public agendas.

Aborigines are acutely aware of the power of news media to create or reproduce public knowledges about race relations, common senses about Aboriginality. Bitter experience has shown all too often how news media constructions of issues involving Aborigines establish the limits of what can and cannot be articulated about them, establish readerships positioned from within a consensus of common sense, and claim for these representations a truth grounded in an ever-present externalized power called ‘public opinion’. However artificial it may be, ‘public opinion’ is for many Aborigines real enough, a thing which governments claim to be powerless in the face of, and thence they will not support Aboriginal land rights, not respect sacred sites, not accept the need for special funding for Aboriginal programs, will scarcely lift a finger against police persecution.

Figure 1

Nowadays Aboriginal affairs form a staple of press and TV news, and this is in no minor way the result of Aboriginal activity itself. Certainly much media coverage exists as a kind of performance space for the ritual playing out of white Australian desires and anxieties, of renegotiating the bipolarity of the tribal and the modern, of revisualizing the boundaries of the deviant and the normal, Nation and Others. While it is a space in which Aborigines are increasingly active performers, pressing all the time for better roles, lines and scripts, as Christine Jennett points out, it is a decidedly white-Australian-controlled theatre:

Media images of and messages about Australian Aborigines are constructed by non-Aborigines operating within the dominant Anglo-European cultural framework for consumption principally by those who share this framework. The reasons for this are located within the history of colonisation of Aborigines by Anglo-Europeans, whose powerful members retain cultural hegemony in Australian society; because they own the means of production, distribution and exchange they also control the dissemination of information about and images of minority groups. Nowhere has this been so all encompassing as in the case of the Aboriginal national minority (1983:28).

I concur with Jennett’s position, which permits a situating of certain news media practices within an array of technologies of repression within an ongoing process of colonization. With this brief indication of the political position from which I proceed, I will move into the more specific background to the material presented here: it is a small portion of what I compiled during my work as a researcher for the Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody, specifically for Commissioner Patrick Dodson’s volumes on the economic, social and legal issues that underlie the deaths and the high rate of imprisonment of Aboriginal people. My brief was to examine the representation of Aboriginal people and issues by news media in Western Australia, to draw conclusions as to the significance of media representations within the cyclical reproduction of the web of hostile and exclusionary social relationships in which Aboriginal people find themselves, and to suggest a range of reforms to media policy, journalistic practices and interventionary measures to empower Aboriginal people.

While there is certainly a need to analyze the full range of media discourse about Aboriginality, I have selected for this paper the emergence of a particular news discourse about Aboriginal youth in Western Australia over the past two years. Specifically, there has occurred a dramatically increased visualizing of Aboriginal youth as criminals, as major instigators of disorder, by Perth newspapers.

Crime reporting, particularly where Aboriginality is identified for no apparent reason, draws the strongest criticism from Aboriginal people themselves. It is the association of Aboriginality with criminality which arguably has the most serious material implications for Aboriginal people, reproducing preconditions for intense police persecution, institutional discrimination and common racism.

Ericson, Baranek, and Chan point out that structuring the production of news in general is an institutional desire for the visualization of deviance. Deviance, its control and its opposite, normality, are in fact the primary discursive objects of news making:

Deviance and control are not only woven into the seamless web of news reporting, but are actually part of its fibre: they define not only the object and central character of news stories, but also the methodological approaches of journalists as they work on their stories (1987:4–5).

It is difficult to nominate a news image more signifying of disorder and deviance in Perth than that of Aboriginal youths. In a sense, ‘reds under the beds’ has become ‘blacks behind the wheel of your car’.

In 1960, at the height of assimilationism, the news media’s ‘Aboriginal problem’ was not represented as a threat to white society, but a question of assisting what were seen as a ‘primitive’ nomadic people to make the ‘transition’ into that society. State and church systems of regulation, surveillance and paternal ‘care’ were firmly in place. In the very broadest terms then, this ‘Aboriginal problem’ as visualized in media had gone from being ‘under control’ in 1960 to ‘out of control’ by the present, and thus ultimately presenting a sense of threat to established orders.

The watershed marking this shift was the controversy surrounding the WA government’s political motioning to legislate Aboriginal land rights in the mid-1980s. In this period, a concentrated anti-land rights media campaign by miners, pastoralists and opposition parties—one TV ad depicting black hands building a brick wall across a map of the state—contributed to turning what opinion pollsters deemed to be ‘ambivalent public attitudes’ into what they called ‘hardened opposition’ not only to land rights, but almost any form of concession to Aboriginal demands (ANOP, 1985). From 1983 to 1989 riots and protests in country towns provided sumptuous spectacles for the front-page imaging of disorder. Needless to say, disorder in public places were the eminently reportable events rather than the conditions for the crisis of Aboriginal life.

Youth in general, of course, are traditionally available within news production, as bearers of moral panic. Throughout 1990 in Western Australia I suggest that the conflux of being black, young and so on the Other side of the Law provided the raw material for a particularly potent media-driven moral panic that has enormously increased the availability of Aboriginal youth as a signifier for certain types of crime and antisocial behaviour, a signifier historically attached to white working-class youth.

From February to July 1990 Aboriginal youth were the specific objects of sensational page-one stories on four occasions. They were featured in many other reports on other pages over this period, and I will be looking at some of these historically, but it is these four front-pages on which I wish to focus. Their positioning made them the major news of the day, but also the circumstances of their production including the timing of their appearance provided a rare opportunity to gain a better grasp of the interplay between two powerful institutional forces—the journalistic practices of visualizing deviance and the state forces which have stakes in maintaining public agendas within which ‘Aboriginal’ crime may be not only meaningful, but useful to the agencies of social control. AsEricson, Baranek and Chan say, news is itself an active control agency. Let’s return to The West Australian headline I began with: ‘Aboriginal gangs terrorise suburbs’. The lead paragraph tells of police fears that ‘the situation is getting out of control’. Two days after the story appeared 45 ABC journalists wrote to the editor of the paper to complain that:

The story proper contained no hard news link to any event or alleged event of the preceding 24 hours. The ‘suburbs’ turned out to be just three adjoining ones. Nobody identified as Aboriginal was quoted on the front page. The story reported allegations by police officers, and hoteliers, and their staff. There was just one allegation detailed which involved a serious attack on a suburbanite in a street. Otherwise the article comprised general remarks by police officers and more specific allegations by persons involved in selling liquor. Alleged crimes at liquor outlets do not amount to terrorised suburbs.3

The journalists’ letter, which The West Australian declined to publish, together with other evidence that the story was of a special kind, that it was an extreme manifestation of the more routinely deployed media discourses about Aborigines, underlined the need for further inquiry.

The reporter who wrote the story told me she had ‘no idea the report was to be given front-page treatment’ and seemed a little surprised but guarded about saying much else except that she had been ‘tipped off about the story’ by a Channel 9 TV news reporter who covered a meeting of irate publicans and civic authorities the previous evening (27 February). Headlines are written by sub-editors, who also determine the positioning of a story, so the most excessive and inflammatory aspects of this story were not in fact the responsibility of the reporter who wrote it.

The Channel 9 TV reporter thought The West Australian’s headline was ‘over the top’ and ‘inflammatory’. He said that the issue involved ‘six to eight or a dozen young Aborigines shop-lifting’, and could even identify a block of flats in nearbyInglewood where most of these youths lived.

Indeed, interviews with suburban police, in whose areas the alleged gang terror occurred, showed that the headline was, even within news media’s own rather elastic conception of fact, groundless. I point out that the following statements are not from the senior police from Police Headquarters on whose statements the story was largely based. The Police Officer-in-Charge of Bayswater Police Station told me the article was ‘disgraceful’ and that the press had ‘blown that out of all proportion’.4 He also said that ‘it is actually quite quiet around here […] we only have a few incidents involving Aboriginal youth’.

He described the article as ‘a piece ofshit’, which he was prepared to ‘stand up in a court of law’ to refute.

To me there was nothing in it. I would have thought they [reporters] would have come to talk to the Officer-in-Charge of the station here. The Aboriginal problem here is no greater than anywhere else.

He strongly refuted the claims of gangs terrorizing the area, or that the ‘situation was getting out of control’. There had been some minor offences, including petty acts of shop-lifting and theft of petrol.

We had a few house break-ins, but you can’t put them down to Aboriginals. I don’t know anything about ‘30 Aboriginals’. It has not been reported to us.

He thought the incidents which the article turned into gang terror amounted to the theft of a cash register from a tavern by three Aboriginal youths who were later arrested by police from another station, the alleged assault on a young woman and her male partner at the Bayswater railway station by Aboriginal youths, and a brawl at theMaylands Tavern which involved Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal adult drinkers. These incidents, he said, were isolated from each other.

The crime figures from the Bayswater Police Station do not support the headline. For instance, in February 1990, at the height of the alleged ‘gang terror’, not a single charge was laid against an Aboriginal youth while three non-Aboriginal youths were arrested for offences including breaking and entering, and stealing. No Aboriginal youths had been sent before the Children’s Court Panel or taken into any form of custody. In the same month five Aboriginal and seventeen non-Aboriginal adults had been arrested.5

Police at neighbouring Maylands presented a very similar picture. A woman constable described the most serious of the incidents involving Aboriginal people as ‘isolated’ and stated that the police had more trouble with ‘white street kids’ than Aboriginal youths.6 There is useful indication here as to the news shift that has occurred, from white youth to Aboriginal youth as the privileged bearers of disorder. She said there had been ‘a bit of a problem in February’ from one Aboriginal family, which had since left the area.

This thing certainly did not deserve this sort of headline. Maylands certainly does not have the problem some people think it has. We don’t get really serious offences here. Ninety per cent of complaints relate toNPPs [No Particular Persons] and most people eventually charged are white. We have a high rate of petty crime, stealing, but the majority of those involved are white. Aboriginal crime has remained pretty standard for the past 18 months with no rise in incidents.

She strongly refuted claims that ‘racial tensions were rising’ and that the ‘situation was getting out of control’ inMaylands.

The only people we’ve been arresting for multiple house break-ins are white people such as drug addicts and street kids. If they [reporters] had looked at the Maylands figures [police arrest book] they would prove that. We’ve never had a call from The West Australian.

Her reaction when first reading the ‘Aboriginal gangs’ story: ‘I thought… you’ve got to be joking! They’re in it for a headline.’ The Maylands police records are similarly revealing. In February 1990 only 7 Aboriginal people were arrested; 5 adults and 2 juveniles, out of a total of 35 arrests. In January, 5 Aboriginal adults were arrested and one Aboriginal juvenile within a total of 27 arrests.7

I believe these comments from police officers patrolling the streets where the all...