![]()

1

Access to the Divine in New Kingdom Egypt: Royal and public participation in the Opet Festival

Kelly Accetta

Access to the divine is the ability for people to have direct contact with their god(s) spiritually and/or physically. In ancient Egypt, it is most often seen in relation to funerary religion, in the intimate nature between the gods and individuals, regardless of status, in their journey into the afterlife. This connection does not apply to the gods of the living, who are often depicted in art and texts as the exclusive companions of the king. It is to the benefit of the ruler to control access to the divine in order to promote themselves as the sole intermediary between the gods and mankind and substantiate their political power. In ancient Egypt, this practice resulted in a distinct divide between state religion and domestic religion. Despite this divide, state religion did not always prevent the public from access to the divine, but rather presented a structured environment in which access was allowed and encouraged.

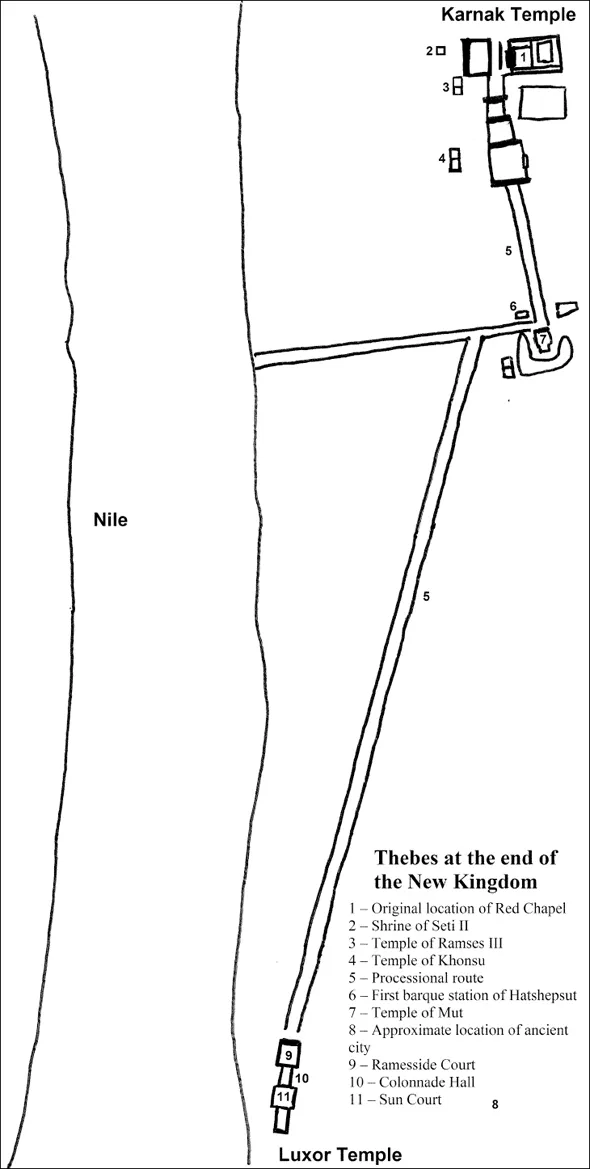

The Opet Festival, celebrated in the New Kingdom (c. 1550–1069 BC), provides a unique opportunity to determine the impact of state religious rituals on public access to the divine. Officially commissioned depictions of the festival show potential occasions for direct contact with the gods, additional inscriptional and pictorial evidence seems to demand the presence of an audience for the success of a festival, and the processional route of the festival ran directly through the sacred landscape of the town of Thebes (Fig. 1.1). In this paper I will investigate how access to the divine during the Opet Festival developed over the New Kingdom by examining opportunities for public participation in the festival.

Access to the divine

It is important to note that in ancient Egypt, access to the divine includes many facets which would not fit into modern religions’ interpretation of access. Egyptian religion believed that the gods were capable of physically manifesting in cult statues located at the heart of their temples, and access to temple and the god was restricted to priests, the king, and royally approved guests (Baines 1991, 183). In a theory put forward by Barry Kemp (1995, 45–6), it is suggested that the temples and shrines of the gods were not always closed off to the public: this restriction of access developed during the Old Kingdom with the establishment of formal state temples, and was enforced throughout pharaonic times. Without access to the temples, the people developed household shrines to ‘domestic gods’, and little evidence survives of public worship of state deities (Baines 1987, 82).

Figure 1.1: The ritual landscape of Thebes at the end of the New Kingdom. Drawing by Kelly Accetta.

A development in the New Kingdom, which scholars refer to as a ‘rise in personal piety’, shows a distinct change in the desire for public access to state gods (Baines 1991, 179). In the city of Amarna, objects in the form of the traditional state gods were found in both elite and workmen’s residences, and chapels from the workmen’s village contained stelae and painted imagery addressing state gods (Kemp 1995, 30). Small temple-shrines to Amun, Ptah, Hathor, and the deified Ramses II at the workmen’s village of Deir el-Medina contained their own cult statues (Lesko 1994, 90). These were paraded through the village on feast days and consulted by the people through local oracle priests (Lesko 1994, 93).

Most significantly, at Karnak Temple – the state temple of Amun-Re and the largest in Egypt – two small temples built on the outer eastern wall of the complex may have been open to members of the public for prayer. The contra-temple of Tuthmosis III contains a statue of the king seated with Amun-Re; it is referred to as the ‘chapel of the hearing ear’ (Blyth 2006, 89). This title recalls New Kingdom stelae which were carved with ears and believed to persuade the gods to listen to the petition written on the stela by the worshipper (Baines 1991, 181). In the case of the chapel, the petitioner was physically present and presented his prayers to the ‘ear’ of the god, in this case the pharaoh was represented by his statue. Later in the Nineteenth Dynasty, Ramses II built a free-standing temple further to the east, which scholars believe served a similar purpose to the contra-temple of Tuthmosis III. In the interior was a false door, which perhaps served to link public petitioners to the sacred shrine of Amun-Re inside the temple, akin to traditional false doors in tombs (Blyth 2006, 159–60). Offerings and petitions made at the door would reach Amun-Re inside his shrine, just as offerings and prayers made by caretakers of the tomb would reach the dead in the underworld.

Returning to my initial point, access to the divine was achieved in several ways in ancient Egypt, all of which must be considered while attempting to determine the opportunities for access to the divine in the Opet Festival. This includes: proximity to the god’s statue or the god’s barque, either whilst at rest or in procession, public participation in the processions or aspects of religious rituals, or as witness to these rituals, oracular consultation or petitioning of the god whilst at rest or in procession, public access to locations which served as ‘hearing ear’ or ‘false door’ connections to the god, public access to the interior of state temples normally off-limits, and finally proximity to, petitioning of, or participation/witnessing of ritual activity concerning the pharaoh, who was the intermediary between the god and mankind. This final point becomes important in the New Kingdom, as the role and powers of the king conflated with those of the god.

The Opet Festival

The Opet Festival was a celebration of renewal centring on the king and Amun-Re. The god rose to prominence in the Egyptian pantheon in the Middle Kingdom, accompanied by an ever-expanding temple complex in the city of Thebes, modern-day Luxor (Wilkinson 2003, 92). As the prominence of the god increased, so did his relationship with the king: by the New Kingdom Amun-Re’s temple at Karnak in Thebes was the largest non-royal landholder and was in a constant state of construction as kings strove to out-do their predecessors in honouring the god (Wilkinson 2001, 50). In return, the god granted the king life and dominion over his empire, and legitimised his reign by acknowledging the king as both an intermediary to the gods and as a god himself (Kitchen 2008, 157). This legitimisation occurred daily in private ritual, but also in public rituals – the Opet Festival was one of these.

The Opet Festival may have arisen as early as the Eleventh Dynasty, but its first surviving recorded performance was not until the Eighteenth Dynasty (Darnell 2010, 1–2). Calendrical texts show the festival occurred in the second month of Akhet, coinciding with the annual midsummer inundation, the re-fertilization of the lands along the Nile (El-Sabban 2000, 29). Just as the Nile’s flood reenergized the lands, so too did the Opet Festival renew the powers of the king. Although textual evidence discussing the purpose of the festival does not survive, texts and pictorial evidence found in temples and tombs records Amun-Re’s promise to grant the king life, health, prosperity, and dominion over the enemies of Egypt in return for his faithful service, offerings, and monuments to the god (Kitchen 1993, 183; 2008, 157).

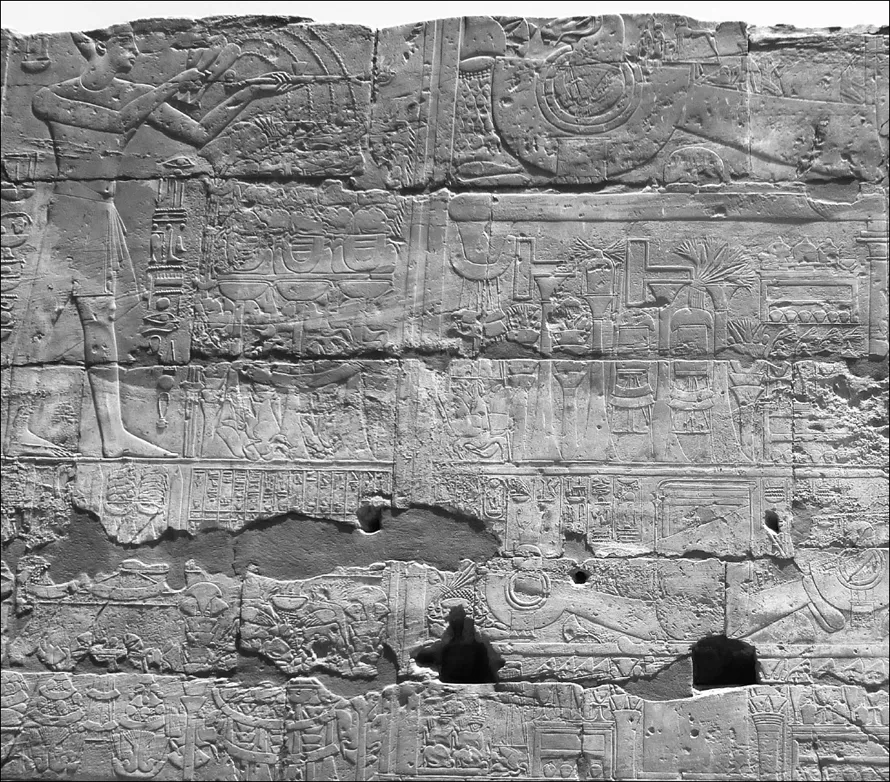

From these sources, scholars are able to piece together some of the activities which occurred during the festival. Nineteenth Dynasty reliefs in the great Hypostyle Hall at Karnak depict the king offering to Amun and censing the barque of the god inside the temple (Kitchen 1999, 391). Then the barque, accompanied by the barque of his consort Mut and their son Khonsu depart south upon the Nile headed for Luxor Temple, where additional reliefs of the festival survive in the Colonnade Hall (Epigraphic Survey 1936, pl. 84; 1994, pl. 17). In reliefs commissioned at Karnak in the Eighteenth Dynasty by Hatshepsut, this journey is made over land along a processional route lined with barque stations (Burgos and Larché 2006, 46–53). Priests carry the barque of Amun-Re while the queen follows behind, censing the barque when it is at rest in each station (Fig. 1.2).

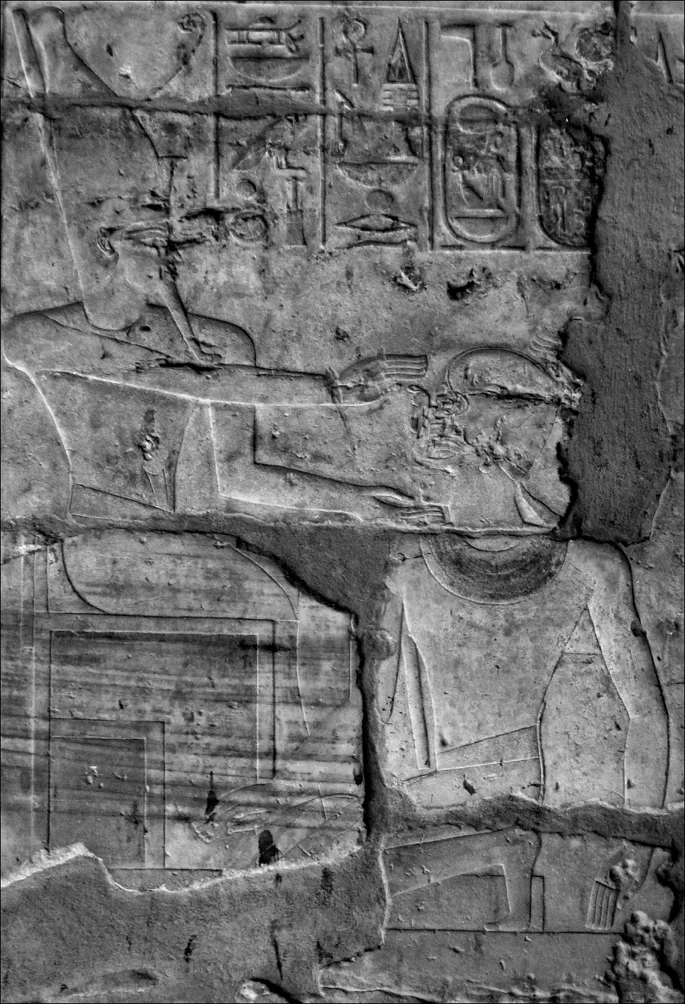

After the barque(s) arrived in Luxor Temple, more offerings were given (Fig. 1.3) and the rituals of renewal performed. While pictorial evidence related directly to the Opet Festival does not depict these rituals, reliefs inside Luxor Temple, where the rituals were performed, indicate they may have included a re-coronation of the king (Fig. 1.4) (Bell 1985, 273; Porter and Moss 1972, 321–4). It is likely that several other rituals were performed during this part of the festival; it is known from textual evidence that the entire festival lasted between eleven days during the reign of Tuthmosis III up to twenty-seven days during the reign of Ramses III, and the processions between the temples would not have lasted more than a day each (Sethe 1907, 824; Grandet 1994, 89).

Figure 1.2: Hatshepsut censing the barque of Amun at rest in a barque station along the processional route. Photo by Kelly Accetta.

Figure 1.3: King censing and offering to the barques of Amun, Khonsu, and Mut at Luxor Temple. Photo by Kelly Accetta.

After the completion of these rituals the barque(s) emerged from Luxor Temple and were loaded onto river barges by priests. The divine barge of Amun, the Userhat, was towed by the barge of the king whilst the others followed in a flotilla bound for Karnak (Epigraphic Survey 1994, pl. 68). Upon landing, further offerings were made to the gods and the king performed other renewal rituals, including the running of the bull as seen in Hatshepsut’s reliefs – a ritual associated with the sed festival, another festival which focused on the renewal of the king’s power and life force (Burgos and Larché 2006, 62–3; Gillam 2005, 29). At the completion of these rituals, the gods’ statues were returned to their shrines until they again processed in other festivals, such as the Beautiful Festival of the Valley, a funerary festival whose origins reach back to the establishment of the temple of Amun-Re at Karnak in the Middle Kingdom (Gillam 2005, 78).

Figure 1.4: Coronation of Amenhotep III by Amun in Luxor Temple. Photo by Kelly Accetta.

It is relevant to note that despite the difference between the festivals, examining known participation in the Beautiful Festival of the Valley and other Middle Kingdom funerary festivals helps to target where and when public participation would be most likely to occur. Regardless of the Opet Festival being a celebration of the cult of the living king while the Beautiful Festival of the Valley celebrated the cult of the deceased king and his ancestors, they both occurred in Thebes and would have involved the same population. Inscriptional evidence from Deir el-Medina suggests that the villagers followed the procession of the barque of Amun-Re after it arrived by barge to the West Bank during the Beautiful Festival of the Valley (Lesko 1994, 91). This would have been an opportunity for oracular consultation with Amun-Re as well as other gods who participated in the festival as they were carried from their shrines in barques amongst the townspeople (Lesko 1994, 91). Some texts indicate it was the movement of the barque which indicated the god’s answer to petitions (Karlshausen 2009, 296–7).

Another funerary festival at Abydos celebrated the state god Osiris, lord of the underworld (O’Connor 2009, 91). Despite his initial association with the deceased king, democratization of funerary religion in the Middle Kingdom led to the belief that all deceased became ‘Osirises’ after death, and the god became important for those seeking to successfully reach the afterlife (Gillam 2005, 55). Records of the actual procession and festival are fragmented, found on stelae erected on either side of the processional route, but do note non-royal participation in the festival, which was a type of re-enactment (Gillam 2005, 57–8). The stela of Ikhernofret, treasurer under pharaoh Senwosret III, boasts that he played a part in the re-creation of the myth of the death and resurrection of Osiris (Lichtheim 1975, 123–125). From these texts, we can hypothesize that privileged elites were the likely actors in a performance which would have required an audience. Whether there was a live audience is not known, but it is known that members of the public also sought participate in and benefit from the festival. Along the processional route other stelae and chapels were dedicated by individuals of varying socio-economic status as cenotaphs, empty representations of tombs, permanent attendees through which the owners might benefit from the funerary cult of Osiris in perpetuity (O’Connor 2009, 93, 96).

Public participation in these festivals, either by building chapels or following the procession, reveals that the democratization of funerary religion did not necessarily provide direct access to the gods. Attendance at these festivals may suggest people were restricted to directly accessing the divine via these public events. It makes sense then, that they would continue to seek to access the divine at state festivals in the New Kingdom.

Additionally, the king may have used the very performative festival to strengthen his political and religious role in the eyes of his subjects. In order for this legitimisation to be successful, the performance of the festival needed to be public; it required an audience as witness. This need for an audience provided opportunities for access to the divine. Despite a lack of textual or pictorial evidence explicitly testifying to public access to the divine during the Opet Festival, comparisons of depictions of the festival, inscriptions adorning the temples involved in the festival, and the archaeological evidence for the landscape of the sacred processional routes shows public access to the divine in the Opet Festival not only existed but increased over the course of the New Kingdom.

Depictions of the Opet Festival

Depictions of the Opet Festival are largely restricted to the processions between Karnak and Luxor which flanked the event – less than ten percent of the whole festival, but the best opportunity for public access to the divine. While some depictions exist in elite tombs, most are officially commissioned reliefs at Karnak or Luxor Temple....