- 586 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Nuclear Safety

About this book

The second edition of Nuclear Safety provides the most up to date methods and data needed to evaluate the safety of nuclear facilities and related processes using risk-informed safety analysis, and provides readers with new techniques to assess the consequences of radioactive releases. Gianni Petrangeli provides applies his wealth of experience to expertly guide the reader through an analysis of nuclear safety aspects, and applications of various well-known cases. Since the first edition was published in 2006, the Fukishima 2011 inundation and accident has brought a big change in nuclear safety experience and perception. This new edition addresses lessons learned from the 2011 Fukishima accident, provides further examples of nuclear safety application and includes consideration of the most recent operational events and data.This thoroughly updated resource will be particularly valuable to industry technical managers and operators and the experts involved in plant safety evaluation and controls. This book will satisfy generalists with an ample spectrum of competences, specialists within the nuclear industry, and all those seeking for simple plant modelling and evaluation methods.New to this edition: - Up to date analysis on recent events within the field, particularly events at Fukushima- Further examples of application on safety analysis- New ways to use the book through calculated examples- Covers all plant components and potential sources of risk, including human, technical and natural factors- Brings together, in a single source, information on nuclear safety normally only found in many different sources- Provides up-to date international design and safety criteria and an overview of regulatory regimes

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Introduction

Abstract

Keywords

1.1 Objectives

1.2 A Short History of Nuclear Safety Technology

1.2.1 The Early Years

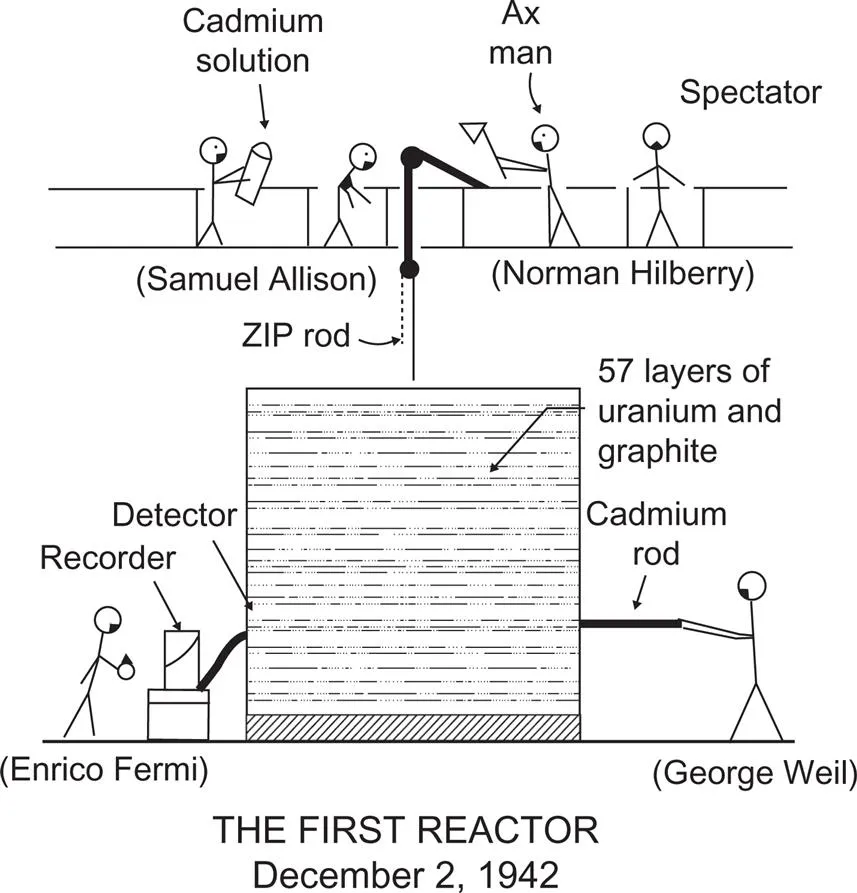

- • Gravity-driven fast shutdown rods (one was operated by cutting a retaining rope with an axe).

- • A secondary shutdown system made of buckets containing a cadmium sulfate solution, which is a good neutron absorber. The buckets were located at the top of the pile and could be emptied onto it should the need arise.

- • the open cycle cooling of the reactors and nonpressure-resistant containments;

- • the disposal of radioactive waste using unreliable methods, such as the location of radioactive liquids in simple underground metallic tanks which were subject to the risk of corrosion and of consequent leaks; and

- • the storage of spent fuel elements in leaking pools of water.

1.2.2 From the Late 1950s to the Three Mile Island Accident

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Preface

- Chapter 1. Introduction

- Chapter 2. Inventory and Localization of Radioactive Products in the Plant

- Chapter 3. Safety Systems and Their Functions

- Chapter 4. The Classification of Accidents and a Discussion of Some Examples

- Chapter 5. Severe Accidents

- Chapter 6. The Dispersion of Radioactivity Releases

- Chapter 7. Health Consequences of Releases

- Chapter 8. The General Approach to the Safety of the Plant–Site Complex

- Chapter 9. Defence in Depth

- Chapter 10. Quality Assurance

- Chapter 11. Safety Analysis

- Chapter 12. Safety Analysis Review

- Chapter 13. Classification of Plant Components

- Chapter 14. Notes on Some Plant Components

- Chapter 15. Earthquake Resistance

- Chapter 16. Tornado Resistance

- Chapter 17. Resistance to External Impact

- Chapter 18. Nuclear Safety Criteria

- Chapter 19. Nuclear Safety Research

- Chapter 20. Operating Experience

- Chapter 21. Underground Location of Nuclear Power Plants

- Chapter 22. The Effects of Nuclear Explosions

- Chapter 23. Radioactive Waste

- Chapter 24. Fusion Safety

- Chapter 25. Safety of Specific Plants and of Other Activities

- Chapter 26. Nuclear Facilities on Satellites

- Chapter 27. Erroneous Beliefs About Nuclear Safety

- Chapter 28. When Can We Say That a Particular Plant Is Safe?

- Chapter 29. The Limits of Nuclear Safety: The Residual Risk

- Additional References

- Appendix 1. The Chernobyl Accident

- Appendix 2. Calculation of the Accident Pressure in a Containment

- Appendix 3. Table of Safety Criteria

- Appendix 4. Dose Calculations

- Appendix 5. Simplified Thermal Analysis of an Insufficiently Refrigerated Core

- Appendix 6. European Requirements Revision E, 2016

- Appendix 7. Notes on Fracture Mechanics

- Appendix 8. US General Design Criteria

- Appendix 9. IAEA Criteria

- Appendix 10. Primary Depressurization Systems

- Appendix 11. Thermal-Hydraulic Transients of the Primary System

- Appendix 12. The Atmospheric Dispersion of Releases

- Appendix 13. Regulatory Framework and Safety Documents

- Appendix 14. USNRC Regulatory Guides and Standard Review Plan

- Appendix 15. Safety Cage

- Appendix 16. Criteria for the Site Chart (Italy)

- Appendix 17. The Three Mile Island Accident

- Appendix 18. Other Examples of Practical Use of This Book

- Websites

- Index