eBook - ePub

Advanced Functional Polymers for Biomedical Applications

- 430 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Advanced Functional Polymers for Biomedical Applications

About this book

Advanced Functional Polymers for Biomedical Applications presents novel techniques for the preparation and characterization of functionalized polymers, enabling researchers, scientists and engineers to understand and utilize their enhanced functionality in a range of cutting-edge biomedical applications.- Provides systematic coverage of the major types of functional polymers, discussing their properties, preparation techniques and potential applications- Presents new synthetic approaches alongside the very latest polymer processing and characterization methods- Unlocks the potential of functional polymers to support ground-breaking techniques for drug and gene delivery, diagnostics, tissue engineering and regenerative medicine

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Advanced Functional Polymers for Biomedical Applications by Masoud Mozafari,Narendra Pal Singh Chauhan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Tecnología e ingeniería & Ciencias de los materiales. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Functional polymers: an introduction in the context of biomedical engineering

Motahare-Sadat Hosseini1,2, Issa Amjadi3, Mohammad Mohajeri4, M. Zubair Iqbal5, Aiguo Wu5 and Masoud Mozafari6,7,8, 1Biomaterials Group, Department of Biomedical Engineering, Amirkabir University of Technology, Tehran, Iran, 2Educational Research Center of Drug Use Disorders and Addictive Behavior, Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences Research Center, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran, 3Department of Biomedical Engineering, Wayne State University, Detroit, MI, United States, 4Nanotechnology Research Center, Pharmaceutical Technology Institute, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Mashhad, Iran, 5CAS Key Laboratory of Magnetic Materials and Devices, Key Laboratory of Additive Manufacturing Materials of Zhejiang Province, Division of Functional Materials and Nanodevices, Ningbo Institute of Materials Technology and Engineering, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Ningbo, P.R. China, 6Bioengineering Research Group, Nanotechnology and Advanced Materials Department, Materials and Energy Research Center (MERC), Tehran, Iran, 7Cellular and Molecular Research Center, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran, 8Department of Tissue Engineering & Regenerative Medicine, Faculty of Advanced Technologies in Medicine, Iran University of Medical Sciences, Tehran, Iran

Abstract

The development of functional polymers has still been an area of immense interest and great importance in biomedical applications. As such, a broad range of approaches for polymerization as well as bioconjugation has been evolved in different contexts. The greatest influence coming out of such efforts is evident as new therapeutic/diagnostic (theranostic) capabilities. The aim of this chapter is to illustrate the part played by functional polymers in emerging biomedical applications, and fast-growing subfields such as tissue engineering, drug delivery, and gene delivery.

Keywords

Biomedical engineering; functionalization; polymers

1.1 Introduction

Functional polymers find an increasing popularity both in academia and in industry. They are macromolecules with unique features and applications [1,2]. The features of this class of materials mostly depend on the presence of chemical functional groups that vary from those of the backbone chains, for instance, polar or ionic functional groups on hydrocarbon backbones or hydrophobic groups on polar polymer chains. Polymer backbones are selected due to their properties ranging from mechanical strength and flexibility to chemical stability and processability [2]. Functionalization of the bulk polymer results in chemical heterogeneity, which, in turn, gives rise to many advantages, namely improved reactivity, phase separation, enhanced compatibility, or association. In addition, the possibility of functional polymers to create self-assemblies or supramolecular structures is another benefit. In response to chemical or physical stimuli, the formation or dissociation of the self-assemblies can lead to “smart” materials [3]. The majority of functional polymers are found on simple linear backbones, including chain-end (telechelic), in-chain, block or graft structures. Nevertheless, functional polymers with particular topologies or architectures have drawn much attention [4,5]. These consist of three-dimensional polymers, for example, stars, hyperbranched polymers [6], or dendrimers [7] (treelike structures) (Fig. 1.1).

Initial technical development in functionalization of bulk polymers occurred during the 1970–80s [8] with the free radical postmodification of polyolefins (PO). This strategy contained the PO modification with peroxide, which acted as a radical initiator, and an unsaturated monomer, such as maleic anhydride and its derivatives [9]. These altered polymers exhibited an increased affinity with polar organic molecules, metals, and minerals, hence they could be also used as effective compatibilizers for a variety of blends [10,11], composites [12], and nanocomposites [13,14]. Such special features apparently arose from the modified structure. However, the use of radical-initiated postmodification for the functionalization process strongly impedes the type (and amount) of functional groups available to be reacted with PO. This limitation directly affects those properties, including tensile modulus, which are ameliorated proportional to the functionalization degree. As a result, to augment the functionalization degree, many efforts have been made by altering the nature of the substrate, of note by considering a more reactive one. In this regard, two basic methods have been proposed; postfunctionalization or synthesis (and polymerization) of functionalized monomers. A typical example is styrenics and acrylates. Thus polymers carrying aromatic groups (e.g., polystyrenes [15]), unsaturation, heteroatoms, either along the backbone or pendant from the main chain, namely poly(acrylate)s, poly(methacrylate)s [16], and so forth, have been shown in the pertained literature as building blocks for functional polymers. Polymerization of functionalized monomers may be associated with undesirable side reactions and slower polymerization kinetics. While in general virtually low functionalization degree is the drawback of the postmodification of bulk polymers. Afterward, other alternative routes, particularly controlled and directed functionalization via “living” polymerization, have been adopted to meet functionalization under mild conditions and minimize the number of synthetic steps [2].

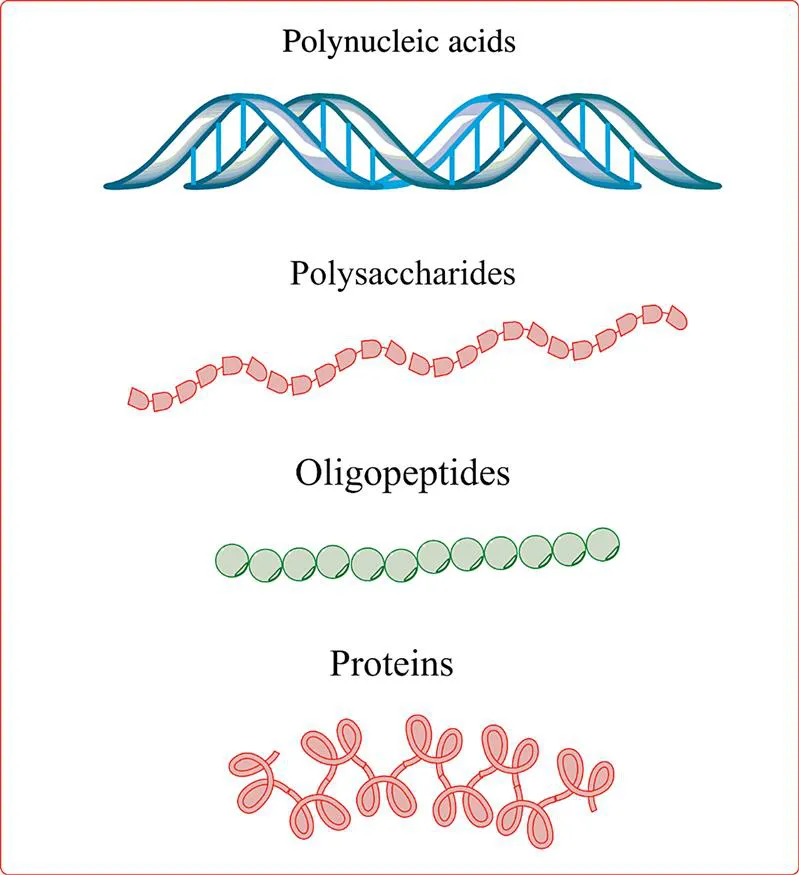

On the other hand, the production of functional polymers encoded with biomolecules has recently been an interesting field of research. Accordingly, a range of polymerization techniques and bioconjugation strategies have been evolved. The notable influence of this work has been observed in biomedicine and biotechnology, where fully synthetic and naturally derived biomolecules are utilized together. The structure as well as function of biopolymers present in nature has been changed over the past thousand years to establish the basis of life. Biofunctional polymers indicate very clearly the diversity accessible via synthesis and semisynthesis using biopolymers (Fig. 1.2). Hancock and Ludersdorf are the pioneers who produced the first artificial polymer in 1840, by treatment of natural rubber with sulfur to fabricate a tough and elastic material [17]. After a century, marked progress in polymer chemistry would produce fully synthetic and complex polymers. Within the past few decades, biocompatible synthetic materials have appeared as one of the most intriguing areas in polymer chemistry, owing to the extensive adoption of living and controlled polymerization strategies (Fig. 1.3). These functional polymeric materials, also known as biosynthetic polymers, are found to have widespread applications in the field of bioengineering, such as novel biomolecule stabilizers, drug-delivery vehicles, therapeutics, biosensing devices, biomedical adhesives, antifouling materials, and biomimetic scaffolds [18–21].

Functional polymers in bioengineering consist of materials that possess in combination synthetic components and biopolymers or moieties designed as mimics of those obtained naturally (Fig. 1.4) [22]. These materials include (1) chemically modified biopolymers (e.g., functionalized hyaluronic acid derivatives [23] or labeled proteins through cell-instruction) [24]. The s...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- List of contributors

- Foreword

- Preface

- Chapter 1. Functional polymers: an introduction in the context of biomedical engineering

- Chapter 2. Grafted biopolymers I: methodology and factors affecting grafting

- Chapter 3. Grafted biopolymers II: synthesis and characterization

- Chapter 4. Conjugated polymers having semiconducting properties

- Chapter 5. Supramolecular metallopolymers

- Chapter 6. Amphiphilic hyperbranched polymers

- Chapter 7. Heterotelechelic multiblock polymers using click chemistry

- Chapter 8. Phenolic and epoxy-based copolymers and terpolymers

- Chapter 9. Maleimide and acrylate based functionalized polymers

- Chapter 10. Functional protein to polymer surfaces: an attachment

- Chapter 11. Functionalized photo-responsive polymeric system

- Chapter 12. Functionalized coordinating polymers

- Chapter 13. Functionalized bioconductive polymers

- Chapter 14. Functionalized polymers for drug/gene-delivery applications

- Chapter 15. Functionalized polymers for diagnostic engineering

- Chapter 16. Functionalized polymers for tissue engineering and regenerative medicines

- Chapter 17. Characterization methodologies of functional polymers

- Chapter 18. State-of-the-art and future perspectives of functional polymers

- Index