- 1,188 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Neurobiology of Language

About this book

Neurobiology of Language explores the study of language, a field that has seen tremendous progress in the last two decades. Key to this progress is the accelerating trend toward integration of neurobiological approaches with the more established understanding of language within cognitive psychology, computer science, and linguistics.

This volume serves as the definitive reference on the neurobiology of language, bringing these various advances together into a single volume of 100 concise entries. The organization includes sections on the field's major subfields, with each section covering both empirical data and theoretical perspectives. "Foundational" neurobiological coverage is also provided, including neuroanatomy, neurophysiology, genetics, linguistic, and psycholinguistic data, and models.

- Foundational reference for the current state of the field of the neurobiology of language

- Enables brain and language researchers and students to remain up-to-date in this fast-moving field that crosses many disciplinary and subdisciplinary boundaries

- Provides an accessible entry point for other scientists interested in the area, but not actively working in it – e.g., speech therapists, neurologists, and cognitive psychologists

- Chapters authored by world leaders in the field – the broadest, most expert coverage available

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Neurobiology of Language by Gregory Hickok,Steven L. Small in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Cognitive Psychology & Cognition. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Section C

Behavioral Foundations

Outline

Chapter 12

Phonology

William J. Idsardi1,2 and Philip J. Monahan3,4, 1Department of Linguistics, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA, 2Neuroscience and Cognitive Science Program, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA, 3Centre for French and Linguistics, University of Toronto Scarborough, Toronto, ON, Canada, 4Department of Linguistics, University of Toronto, Toronto, ON, Canada

Phonology is typically defined as the study of speech sounds of a language or languages and the laws governing them, particularly the laws governing the composition and combination of speech sounds in language. This definition does reflect a segmental bias in the historical development of the field and we can offer a more general definition: the study of the knowledge and representations of the sound system of human languages. From a neurobiological or cognitive neuroscience perspective, one can therefore consider phonology as the study of the mental model for human speech.

Keywords

Phonology; speech; language; syllables

12.1 Introduction

Phonology is typically defined as “the study of speech sounds of a language or languages, and the laws governing them,”1 particularly the laws governing the composition and combination of speech sounds in language. This definition reflects a segmental bias in the historical development of the field and we can offer a more general definition: the study of the knowledge and representations of the sound system of human languages. From a neurobiological or cognitive neuroscience perspective, one can consider phonology as the study of the mental model for human speech. In this brief review, we restrict ourselves to spoken language, although analogous concerns hold for signed language (Brentari, 2011). Moreover, we limit the discussion to what we consider the most important aspects of phonology. These include: (i) the mappings between three systems of representation: action, perception, and long-term memory; (ii) the fundamental components of speech sounds (i.e., distinctive features); (iii) the laws of combinations of speech sounds, both adjacent and long-distance; and (iv) the chunking of speech sounds into larger units, especially syllables.

To begin, consider the word-form “glark.” Given this string of letters, native speakers of English will have an idea of how to pronounce it and what it would sound like if another person said it. They would have little idea, if any, of what it means.2 The meaning of a word is arbitrary given its form, and it could mean something else entirely. Consequently, we can have very specific knowledge about a word’s form from a single presentation and can recognize and repeat such word-forms without much effort, all without knowing its meaning. Phonology studies the regularities of form (i.e., “rules without meaning”) (Staal, 1990) and the laws of combination for speech sounds and their sub-parts.

Any account needs to address the fact that speech is produced by one anatomical system (the mouth) and perceived with another (the auditory system). Our ability to repeat new word-forms, such as “glark,” is evidence that people effortlessly map between these two systems. Moreover, new word-forms can be stored in both short-term and long-term memory. As a result, phonology must confront the conversion of representations (i.e., data structures) between three broad neural systems: memory, action, and perception (the MAP loop; Poeppel & Idsardi, 2011). Each system has further sub-systems that we ignore here. The basic proposal is that this is done through the use of phonological primitives (features), which are temporally organized (chunked, grouped, coordinated) on at least two fundamental time scales: the feature or segment and the syllable (Poeppel, 2003).

12.2 Speech Sounds and the MAP Loop

The alphabet is an incredible human invention, but its ubiquity overly influences our ideas regarding the basic units of speech. This continues to this day and is evident in the influence of the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA; http://www.langsci.ucl.ac.uk/ipa/) for transcribing speech. Not all writing systems are alphabetic, however. Some languages choose orthographic units larger than single sounds (moras, syllables) and a few, such as Bell’s Visible Speech (Bell, 1867) and the Korean orthographic system Hangul (Kim-Renaud, 1997), decompose sounds into their component articulations, all of which constitute important, interconnected representations for speech.

12.2.1 Action or Articulation of Speech

The musculature of the mouth has historically been somewhat more accessible to investigation than audition or memory, and linguistic phonetics has often displayed a bias toward classifying speech sounds in terms of the actions needed to produce them (i.e., the articulation of the speech sounds by the mouth). For example, the standard IPA charts for consonants and vowels (Figure 12.1) are organized by how speech sounds are articulated. The columns in Figure 12.1A arrange consonants with respect to where they are articulated in the mouth (note: right to left corresponds to anterior to posterior position within the oral cavity), and the rows correspond to how they are articulated (i.e., their manner of articulation). The horizontal dimension in Figure 12.1B represents the relative frontness-backness of the tongue, and the vertical dimension represents the aperture of the mouth during production. These are the standard methods for organizing consonant and vowel inventories in languages.

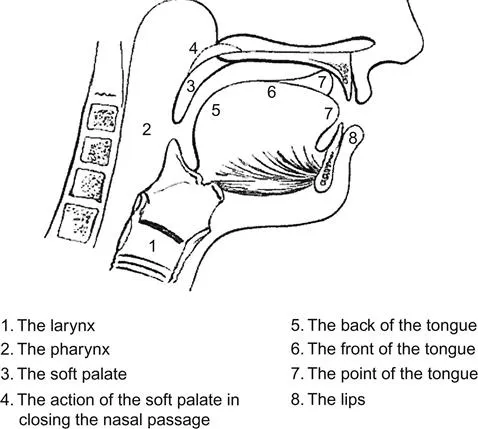

Within the oral cavity, there are several controllable structures used to produce speech sounds. These include the larynx, the velum, the tongue (which is further divided into three relatively independently moveable sections: the tongue blade, the tongue dorsum, and the tongue root), and the lips (see Figure 12.2 reproduced from Bell, 1867; for more detail see Zemlin, 1998).

Each of these structures has some degrees of freedom of movement, which we describe in terms of their deflection from a neutral posture for speaking. The position for the mid-central vowel schwa, [ə], is considered to be the neutral posture of the speech articulators. In most structures, two opposite directions of movement are possible, yielding three stable regions of articulation, that is, the tongue dorsum can be put into a high, mid (neutral), or low position. In the neutral posture the velum is closed, but it can be opened to allow air to flow through the nose, and such speech sounds are classified as nasal (as in English “m” [m]). The lips can deflect from the neutral posture by being rounded (as in English “oo” [u]) or drawn back (as in English “ee” [i]). The tongue tip can be curled concavely or convexly either along its length (yielding retroflex and laminal sounds, respectively) or across its width (yielding grooved and lateral sounds, respectively). The tongue dorsum (as mentioned) can be moved vertically (high or low) and horizontally (front or back), and the tongue root can be moved horizontally (advanced or retracted).

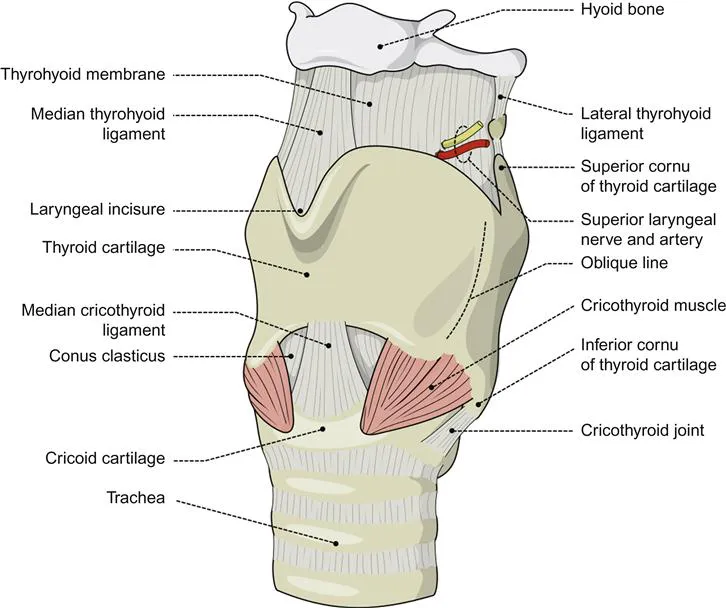

The larynx (Figure 12.3) is particularly complex and can be moved along three different dimensions: modifying its vertical position (raised or lowered), modifying its tilt (rotated forward to slacken the vocal folds or rotated backwards to stiffen them), and changing the degree of separation of the vocal folds (adducted or abducted). Furthermore, the lips and the tongue blade and dorsum can close off the mouth to different degrees (termed the “manner” of production): completely closed (stops), nearly closed with turbulent airflow (fricatives), or substantially open (approximants). Taken together, these articulatory maneuvers describe how to make various speech sounds. For example, an English [s], as in “sea”, is an abducted (voiceless, high glottal airflow) grooved fricative. Furthermore, as described in Section 12.3, the antagonistic relationships between articulator movements serve as the basis for the featural distinctions (whether monovalent, equipollent, or binary; see Fant, 1973; Trubetzkoy, 1969) that have proven so powerful in understanding not only the composition of speech sounds but also the phonology of human language.

12.2.2 Perception or Audition of Speech

A great deal of the literature regarding speech perception deals with how “special” speech is (Liberman, 1996) or is not. Often, this is cast as a debate between the motor theory of speech perception (Liberman & Mattingly, 1985) and speech as an area of expertise within general auditory perception (Carbonnell & Lotto, 2014). The motor theory of speech perception posits speech-specific mechanisms that recover the intended articulatory gestures that produced the physical auditory stimulus. General auditory perception models, however, posit that the primary representational modality of speech perception is auditory and the mechanisms used during speech perception are the same as those responsible for nonspeech auditory perception. This dichotomy, in some ways, parallels debates about face perception (Rhodes, Calder, Johnson, & Haxby, 2011). Since the development of the sound spectrograph (Potter, Kopp, & Green, 1947) and the Haskins pattern playback machine (Cooper, Liberman, & Borst, 1951), it has been...

Table of contents

- Cover image

- Title page

- Table of Contents

- Copyright

- Dedication

- List of Contributors

- Acknowledgement

- Section A: Introduction

- Section B: Neurobiological Foundations

- Section C: Behavioral Foundations

- Section D: Large-Scale Models

- Section E: Development, Learning, and Plasticity

- Section F: Perceptual Analysis of the Speech Signal

- Section G: Word Processing

- Section H: Sentence Processing

- Section I: Discourse Processing and Pragmatics

- Section J: Speaking

- Section K: Conceptual Semantic Knowledge

- Section L: Written Language

- Section M: Animal Models for Language

- Section N: Memory for Language

- Section O: Language Breakdown

- Section P: Language Treatment

- Section Q: Prosody, Tone, and Music

- Index

- Sync with Jellybooks